I believed that Kurt Cobain was going to change the world. After suffering through years of shitty hair metal and poor pop rap, Cobain and Nirvana blasted open the doors of the culture with Nevermind and ushered in what looked like an invasion of the great underground I knew had been percolating for years. But it wasn’t to be – the alternative/punk revolution faltered as soon as it began, which I guess isn’t that surprising when you realize its ethos was slackness. The scene and the sound were co-opted right away, and Nirvana only released one more real album before Cobain killed himself one April day in 1994, closing the door he had opened. There was great music before Smells Like Teen Spirit fractured the charts, and there was great music after they found Kurt’s body in that greenhouse, but the idea that the alternative/punk scene would dominate the Earth really only worked in those few short years.

I believed that Kurt Cobain was going to change the world. After suffering through years of shitty hair metal and poor pop rap, Cobain and Nirvana blasted open the doors of the culture with Nevermind and ushered in what looked like an invasion of the great underground I knew had been percolating for years. But it wasn’t to be – the alternative/punk revolution faltered as soon as it began, which I guess isn’t that surprising when you realize its ethos was slackness. The scene and the sound were co-opted right away, and Nirvana only released one more real album before Cobain killed himself one April day in 1994, closing the door he had opened. There was great music before Smells Like Teen Spirit fractured the charts, and there was great music after they found Kurt’s body in that greenhouse, but the idea that the alternative/punk scene would dominate the Earth really only worked in those few short years.

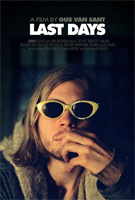

Considering how important Kurt and his music were to me, I suppose I was equally predisposed to love or to hate Gus Van Sant’s Last Days. The film is ostensibly an examination of the final hours of a guy named Blake, who we take to be a troubled rock star, but it’s obvious that it’s about Cobain. The odds of me hating it were greater, I assumed, just because I hated the idea of Van Sant exploiting Kurt and his mysterious final days of life.

But it turns out that Van Sant has made a film just short of a minor masterpiece, a movie that resonates more deeply with me because of my love of Cobain but one that works outside of that identification. He’s taken the elliptical style of Gerry and Elephant and refined it to perfection here – Last Days is almost non-narrative and ethereal, a shambling movie that evokes more than it says. It’s experiential, and as such most audiences will reject it, but if you’re willing to put in the work and to follow Van Sant as he goes where the film takes him, you’ll get brilliance out of it.

Last Days rests solely on the shoulders of Michael Pitt, an actor who has been around long enough now to have made it bigger than he is. He certainly has the good looks of a movie star (specifically the slightly effeminate looks that our modern young movie stars seem to have), although I’ve never been convinced of his acting chops. He was easily the weakest link in Hedwig and the Angry Inch, and when you underwhelm me on an episode of Law & Order there’s something wrong. But here he’s perfect, submerged completely in the character and hidden behind stringy blonde hair and big sunglasses and hoods. He mutters and staggers through the picture, delivering next to no lines but doing the kind of full body acting you see in silent films.

He is briefly surrounded by other characters – hangers on who are crashing at Blake’s house – but they’re really just annoyances, things that get in the way of the main story. Honestly, I would have rated the film much higher if these characters weren’t in it (and they bring with them a completely, bizarrely gratuitous gay love scene that left me confused and baffled), but then I suppose Last Days would have been about 45 minutes long. There’s a brief appearance by Ricky Jay, playing what seems to be Ricky Jay as a detective, that doesn’t bog things down too much. And it’s always a joy to see Ricky Jay.

But you always want to go back to Pitt. You want to see some hint of what it is that’s torturing him. The film shows no drug use, has no expository dialogue, doesn’t even tell you who Blake is or why he is wandering in the woods when the film opens (although knowing what I do about Cobain and judging by the medical bracelet on Blake’s wrist I would guess he had just escaped from rehab). It never lets you in, and that’s intriguing. Here Van Sant is showing us a chronology of the actions of this man’s last days, him eating macaroni and cheese, playing a guitar, wandering around, but what he is saying is that the mystery can never be solved. What he was doing is unimportant, the action was all within. And we’re denied that.

We’re mostly denied that, I should say. There’s a scene where Blake plays an improvised song in his recording studio, and we briefly glimpse what’s boiling inside of him. It’s one of those scenes, by the way, that people will be aping and talking about for decades – it’s sheer greatness as Van Sant’s camera slowly dollies away from the window looking into the room (we’re never inside) and Pitt goes from instrument to instrument, adding layers to this song, climaxing with his ragged screaming voice. It’s haunting to watch, and it’s as close as Blake gets to communicating what’s inside of him – maybe that’s the only way to communicate it, with screeching feedback and throat shredding yelps. I certainly believed that back in 1992.

There are some tricks that Van Sant uses here that are fascinating, but possibly in the wrong film. He shows some scenes again and again, in full, but from different character’s points of view. Since I found it hard to really care about anyone who wasn’t Blake this stuff was fascinating in a purely cinematic way but never emotionally engaging.

I have to admit that I found myself puzzled as to why this movie is about Blake and not Kurt. Every item of clothing Blake wears in the film will be familiar to anyone who followed Nirvana throughout their career – they’re all clothes Cobain wore on TV or in photo shoots. Pitt gets no close ups in the film until the very end, and with his face constantly obscured he looks an awful lot like Kurt. It creates an odd disconnect that can be distracting, as you wonder which parts are really about Kurt and which are just coming from Van Sant and Pitt. It’s certainly not helped by the fact that the MTV news footage of Blake’s death is – you guessed it – just the MTV news coverage of Kurt’s suicide. If you want to see a Cobain film, this isn’t it. Sort of.

But even with the weaknesses, Van Sant has crafted a film as brave as it is difficult. He’s been a filmmaker of tremendous talent before (My Own Private Idaho is, in my opinion, one of the all time great films) but he’s also shown that he’s more than willing to pander to an audience (Finding Forrester is a terrific example of how maybe the auteur theory needs some work). Here he’s in fine artistic form, and Last Days will be especially rewarding to those who saw his last two films. These movies form a triptych where Van Sant meditates on death and isolation, with each being head and shoulders above the last.

I can’t imagine that it’s much of a spoiler that Blake dies at the end. Van Sant doesn’t show us the moment, and doesn’t even really specify how it happens – overdose or gunshot? Was it even fully intentional? It’s mysterious, like everything else. But there is one mystery Van Sant cracks in a strange scene that veers suddenly away from the psuedo-documentary feel of the picture as Blake’s soul rises out of his dead body and climbs out of frame, up to what we must assume is heaven. It’s a touch of magical realism and I still haven’t decided if I like it – the imagery is a little standard for a film this avant, and I couldn’t help but wonder if Van Sant personally needed to put a touch of hope at the end of Blake’s bleak final moments.

Last Days isn’t for the casual filmgoer, and people drawn just by the Cobain elements are likely to be disappointed. It’s a delicate and yet demanding film, one that will reward the patient viewer with visions of beauty and despair.

8.6 out of 10