BUY FROM AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

BUY FROM AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

STUDIO: Magnolia Home Entertainment

MSRP: $14.49

RATED: R

RUNNING TIME: 94 Minutes

SPECIAL FEATURES:

- Commentary with Gareth Edwards, Scoot McNairy, and Whitney Able

- Deleted and Extended Scenes

- HDNet: A Look at Monsters

The Pitch

28 Cloverfields Later

The Humans

Director: Gareth Edwards

Writer: Gareth Edwards

Cast: Scoot McNairy, Whitney Able

"Who's Zed?"

The Nutshell

6 years ago, a NASA space probe believed to have located alien life brought a few unwanted surprises back to Earth. Mexico is now awash with Lovecraftian undesirables and all that stands between this “infected zone” and the USA is “The Wall”, a huge military shield. Stroppy photographer Andrew Kaulder (McNairy) must get rich-girl Sam Wynden (Able) home on American soil by trekking through the heart of darkness within two days or she’ll be stranded on the other side for 6 months… and her father – who just happens to be his boss – will be none too pleased about that.

The Lowdown

It’s hard to believe how far science-fiction has come. Long before Lycra and spandex-clad muscle-men swung to the top of the summer schedule, studios were pumping top dollar into sending Tom Hanks or Will Smith into outer space. Or when we were very good boys and girls, into sending Will Smith and Jeff Goldblum into outer space together. Even Roger Corman’s lower budget New World Pictures had fatter wallets than the most buoyant indies, not to mention a few familiar faces like John Saxon (Battle Beyond the Stars) or Sid Haig (Galaxy of Terror) in the mix for the adverts. Horror and comedy may have long been the studios’ favourite low-risk money spinners, but digital effects are changing all that. Suddenly, the big boys’ toy-chest has been raided and the ramifications are vast and wonderful. In the process, the overwhelming odds against a DIY science-fiction film looking credible have been slashed. Low budget used to mean discarded Big Mac boxes painted to look like a ship’s hull and stuck to a wall. Nowadays, the term conjures images of Duncan Jones’ Moon. The times, they are – how you say – a changin’?

Crack open some red hair dye and I'd say this Jill Valentine fan movie's got potential.

And Gareth Edwards is showing them how through a combination of passion, talent, and audacity. A lot has been made of how the Brit’s debut directorial feature was made on the fly across Central America with unknowns, and how Edwards handled the visual effects (as well as production design and cinematography) himself on software available from all good electronics stockists. If you’re reading this, you’re probably sick of hearing about it. It is, after all, certainly not the first film to tackle a high concept on a lower budget scale. The likes of [Rec] have shown a knack for cutting corners without compromising quality in recent years. However, Monsters is (sorry, can’t resist) a different beast. Although it’s realized by mostly non-actors and much of the dialogue was improvised, this isn’t another genre film following the cinéma vérité model. It’s a modern take on the classic monster movie done *almost* within the everyman’s means. What if Godzilla or Gamera or a whole host of their mammoth chums ran amok not in Japan or on another world, but right at your door? What if they did it so often it became as much a part of everyday life as a paperboy making his rounds? It’s a wonderful concept. Not only is it an engrossing riff on the monster movie genre, but it’s also a cheeky dare to every armchair auteur: come and have a go if you think you can do better.

A quick glance at the film’s IMDB or Amazon pages says an awful lot. For every comment that praises the film’s originality and vision, there’s one that that echoes Otto the Bus Driver’s immortal protest “flavoured false advertising.” Apparently, Thundercrotch_Nutblaster85 and friends felt a tad mislead. “WERZ TEH ALIENZ?!#1?1” (sic) seems to be the general consensus. Too much romance, not enough stampeding giants. As is so often the case with films like this, that backlash only tells half the story. Monsters doesn’t pull a Troll 2; there are monsters present. Quite a few in fact, and they’re perfectly comfortable reeking havoc whenever it suits them. The very people complaining the film didn’t live up to its promise fell in love with their own idea of Monsters not Gareth Edwards’. Instead of giving the film playing in front of them a chance, they rejected it on the grounds that it wasn’t just its (deliberately ambiguous) title. The film’s central narrative – Andrew trying to get Sam through the infected zone to her fiancée and family so she isn’t trapped on the other side for half a year – wasn’t withheld from bloodthirsty viewers clamoring for Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em, Rodan. This story and how it intermingled with the monster action was what helped sell the film and garner rave reviews all along.

"Ladies and gentlemen, we'll shortly be docking in Northern Ireland. Please be sure to avoid eye contact with the *ahem* coast guard, to prevent one of them challenging you to a 'staring match.'"

It’s easy to see why. When we meet Andrew and Sam, they couldn’t be less on the same page. He’s an arrogant jerk out only for himself and his work and she’s the brittle Daddy’s girl getting in the way, struggling to keep up with all the chaos around her. It’s your typical Riggs/Murtaugh formula throwing these two together, but unlike a lot of genre films, the archetypal aspect soon melts away. McNairy and Able deserve a great deal of the credit for this. The pair – now married, of course, in real life – get to know each other over a first act fraught with obstacles and falling-outs. It’s this prologue section where the deadline for their mission is set in place that defines them as flesh and blood characters rather than cardboard cut outs. Edwards was wise to use improvised dialogue. The film’s framework is knowingly conventional and this naturalistic approach helps the performances elevate the other stale aspects. Casting a couple with real-life history to play his romantic leads pays off big for Edwards. Their natural rapport has an ease that gets around the notoriously treacherous chemistry minefield. A bit of on the nose dialogue is one thing, but if the leads didn’t convince as a pretty conventional couple coming together through adverse circumstances or, worse yet, weren’t interesting, nobody would care if they got eaten or not. The romantic subplot between Patrick Stewart and Alfre Woodard was cut from Star Trek: First Contact because it was feared that people wouldn’t believe love could blossom amidst the threat of assimilation. Excising that story was a mistake because it ignored the inextricable link between sex and death. Desire has an odd way of running highest at inopportune times so it’s perfectly plausible that the prospect of death – especially unusual death – would not only cancel out this impulse but increase it. Even if all the other ingredients misfired in Monsters, the charming rapport at its heart would ensure at least one box was ticked. We genuinely want to see if these two can make it to the end of the tunnel and whether or not they’ll wind up together when they get there… an all too rare reaction in the sci-fi/horror realm.

I mentioned before how the film’s detractors didn’t realize exactly what they were in for. Well, a lot of that is due to the levels it works on. Monsters is about more than just rampaging creatures, something I presume its haters will come to appreciate once they turn 16. Like all worthy science-fiction, it shows us a reflection of ourselves as well as lots of cool explosions and tentacles. On the surface, there are several mini-movies all going on at once. You’ve got your action-adventure ultimatum à la Escape from New York. You’ve got your “will they/won’t they” romantic arc. You, of course, have your alien horror quotient. And you’ve also got something deeper. It might not be as “deep” as it wants to be (Edwards himself even notes on the commentary the film shouldn’t be read too heavily into) but that’s more to do with how loosely sketched the themes are, not that there aren’t any. Like Cloverfield, this is not the story of Planet Earth’s battle against these aliens. World Invasion – Battle: Mexico City this most definitely isn’t. Monsters is the intimate story of how extraordinary circumstances impact on the average Joe and the girl he’s got his eye on. Consequently, we’re treated to extensive marketing. Not only in the form of the numerous signs Sam and Andrew encounter on their journey (which Edwards cunningly edited in Photoshop to “alien them up”) but also in TV commercials and news bulletins. Post 9/11 there’s a certain amount of reading into things most viewers will do without invitation so the metaphorical ramifications of a hostile force infiltrating society quickly become apparent. In essence, the battle becomes a resident in us. That much you can almost get without even seeing the film. It’s more or less the film’s UK tag-line. These clips reach an audience wider than their intended demographic though. Earth’s newest inhabitants, themselves a nebulous collection of walking squid lava lamps, are drawn to them as well. All of these commercials and news reports are beautifully done, especially an instructional kid’s cartoon for gas mask operation. However, there’s more to them than just Edwards tipping his hat to Paul Verhoeven. The unshakable media presence in Monsters is the key to understanding how wrong Joe Schmo really is about it. Two scenes towards the end, one atop a Mayan temple and the other outside a gas station, may bring what’s on Edwards’ mind a little too sharply into focus, but what’s on his mind and the manner in which he goes about raising his points more than gets him a pass. Despite what Mr_Turbo_Balls protests.

"What do you MEAN Rambo 'retired'?"

To say any more will give it away so I’ll move onto my only real bone of contention with the movie which, ironically, is the very thing that contributed so much to the hype around it: the special effects. I’m by no means the pickiest guy in the world when it comes to VFX, be they practical or digital. I still love me some stop-motion Tauntaun action and it is my firm belief that we can ill afford to forget Klendathu, a truly evergreen case of CGI if ever there was one. However, when I hear the effects in a hotly-tipped independent film are just as good as the most expensive major studio picture, they darn well better be. It’s for this reason that I was a little disappointed with Monsters. I don’t think the effects deserved the level of saliva spilled over them. And I’m not saying that to be “controversial.” I think I’ve spent enough time lamenting online contrariness to be believed about that. There’s no getting around the fact that Gareth Edwards did an incredible job with the resources available to him. But no amount of hype in the world could convince my eyes the cartoon style blurriness around the edges of all those wrecked warships or destroyed architecture is humidity and not the telltale sign of CGI, the digital equivalent of a visible string. If all I’d heard going in was “the effects in Monsters, though not quite as impressive as a blockbuster’s, are awfully slick for a one-man effort” I would’ve agreed completely. Everyone who took that a step further was getting a little carried away. I’d urge anyone to watch the sketchy Jaws homage with the crashed fighter plane again before telling me off.

That complaint aside, the special effects work best after sundown. The opening night-vision military sequence is probably already inspiring missions in a future Call of Duty. A sudden boom interrupts a routine trip. Screams. Gunfire. Darkness. Video interference. A – what is that? A leg? Legs? Darkness. More gunfire. It’s probably as close as we’ll ever get to seeing a spin-off of The Mist which follows the army and Edwards chooses what to show and what not to show superbly. Frank Darabont’s film is a good comparison for complaints, incidentally. The effects are by no means bad, it’s just that they aren’t quite good enough to meet your suspension of disbelief halfway every time. Oddly enough, in a film that’s more “realistic” in some ways like this, it’s more damaging to have this kind of effects problem than it is in, say, Sin City. When something is as obviously stylized as that or another green-screen heavy film like 300, it automatically adjusts your eyes to the new terrain more or less immediately, like putting on a pair of 3-d glasses. Here, the effects are intended to break down such a wall and convince you it’s all “real”, a riff on this reality as opposed to a completely fresh one, and they simply aren’t good enough to do that. Don’t be surprised if they suck you out a lot of the time just as things start hotting up.

Banksy may have become a tad complacent.

Although the film’s big selling point (the clue’s in the title) are no shrimps themselves, one of the most interesting things about them is their classification. They’re a massive fish-like species – Edwards expands on this in the commentary – who’ll feel the right kind of familiar to fans of Lovecraft. For all their tentacles and lanky legs, Edwards treats his monsters more like zombies than little Godzooky size alien squids, right down to having his characters address them as “creatures”, the now customary alternate designation instead of their literal name. A few opening title cards catch us up to what’s been going on since they arrived unannounced and it all went spectacularly wrong for Latin America. The status quo here isn’t the heat of the moment when it all kicked off. It’s 6 years after that. We join Andrew and Sam in a sort of prequel/remake of Land of the Dead with zombies swapped for alien “fish”. This is no longer a new menace; it’s part of everyday life. They’re out there, sniffing around the fences and walls put up to keep them at arm’s length. “Outbreaks” are not uncommon, but there’s an infrastructure in place to try to deal with it. Try being the key word.

There’s a saying about time and limitation that’s particularly salient here. It’s somewhere between”necessity is the mother of invention” and Occam’s Razor. The British indie band Editors even referenced it in one of their early singles: “if something has to change, then it always does.” If you’ve got a day to do something, according to this belief, it’ll get done in a day. Like a kid who’s got ten minutes to finish his essay before it’s pencils down or a writer pushing to make a review deadline *meta*. On the commentary, Edwards states that he thinks more money wouldn’t necessarily have improved his film. McNairy agrees with him and I’m inclined to second that, save for the special effects. Without the budget or crew traditionally available, everyone in front of and behind the camera clasped hold of every available shot or opportunity. A number of moments occurred during filming (notably, a sunset scene) that weren’t in the treatment, but were included spontaneously since they were deemed too good to pass up. This kind of organic creativity combined with the pressure of the shoot gelled beautifully and the results are on the screen for all to see. I can’t imagine it’s a relaxing working environment to be shooting amidst drug wars and swine flu alerts but the ends make a convincing case for the means. It wouldn’t surprise me if Edwards was the type of student who started revising for his coursework the night before it was due in because the whole film has an urgency that suggests Sam and Kaulder’s one strike “we might not get another shot at this” circumstances were mirrored by events behind the camera. Some shrewd editing lends even the most throw-away exchange or respite from running around a deliberateness that suggests even the moments that were born of necessity rather than choice were supposed to be that way all along.

"I'm not even supposed to BE a scruffy Adam Goldberg today."

Going into Monsters for the first time after the hubbub had already died down allowed me to see clearly that it’s a remarkable first effort from a highly promising filmmaker. A dress-rehearsal more than the finished article it may be, but what a dress rehearsal. It bodes very well for just about everyone… except the droves sure to be stomped on when Edwards reboots Godzilla. Unlike with his debut, I plan to be there opening night.

The Package

There isn’t a great deal of bonus material on this disc and the only feature of real quality is the commentary between the director and his two stars. Equal parts anecdotal and technical, it offers something for the casual and seasoned film-fan alike. Edwards shows none of the bashfulness that sometimes hampers directors’ contributions to commentaries and he reveals how he cut corners and posits theories on the film’s scenes with the willingness of a fan rather than a creator. Very often, he plays the magician next door who loves nothing more than to reveal his tricks. Many variations on “that *blank* wasn’t really there, obviously” get trotted out, but it’s nice to hear a commentary where the director and actors sound like friends on a level pegging rather than a teacher and his slightly intimidated students.

The scenes filmed in Galveston, Texas in the wake of an actual hurricane take on a different dimension here. From a purely practical sense, that location afforded Edwards the opportunity to utilize an incredible amount of genuine destruction for a massive “aftermath” moment. “Ready-made production design”, in a manner of speaking. Not only that, but allowing actors to wade through the wreckage of people’s lives led to some powerful reactions from McNairy and Able. The horror on their faces is probably truer than most considering both actors hail from Texas. Edwards reveals that a small donation was enough to grant him access to this site, but there comes a point where the ethics of such an approach must come into play. Some might argue that filming in this way can be seen as a positive since it allows something “good” (art) to come of something bad (death, destruction, and real human loss.) Still… imagine how you might feel if the aftermath of a Middle-Eastern skirmish was used similarly in a war film instead of the wreckage from a natural disaster on American soil. Footage of where Allied soldiers had really fought and possibly even been killed. Consider the difference, then ask yourself how you feel about it.

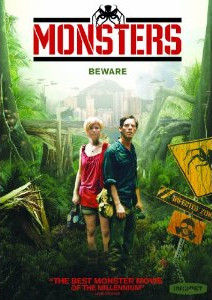

Otherwise, 4 deservedly cut deleted/extended scenes and an HDNet promo fluff piece are all she wrote as far as special features go. It’s a pretty lackluster showing given the amount of creature and special effects design that went into the film. Edwards amassed numerous sketches whilst designing the creatures so there’s really no excuse for ignoring such a mammoth design process. Even a brief stills gallery would suffice (I smell an impending double-dip.) A/V presentation is solid. Too solid, in fact. If the picture and sound weren’t so impressive, maybe the effects wouldn’t prove so distracting. But the same can’t be said for the truly lamentable cover art (see above.) Maybe someone felt that, with all the Photoshop in the film itself, no-one would mind if the cover art got phoned in. Slapping a cut and paste job as lazy as that on to what is unmistakably a labour of love sums up the missed opportunity that is this release.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars