BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

STUDIO: Palm

MSRP: $24.99 RATED: Unrated

RUNNING TIME: 109 Minutes

SPECIAL FEATURES:

• Cast and crew interviews

• Behind-the-scenes featurette

• Original Korean trailer

• Music video

• Trailers for other Palm features

• DVD-ROM weblinks

Park

Chan-wook is justly famous these days for directing Oldboy, his third

feature. Oldboy is part of Park’s Vengeance Trilogy, which was begun in

his second feature, Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance. JSA (unrelated to the DC

comics) is a completely different animal from either of those films. Where they

explore various degrees of burning revenge, JSA examines a much more

collected set of characters, and is concerned with brotherhood, friendship and

redemption (or the lack thereof).

The

screenplay is a quietly stunning examination of characters on both sides of the

demilitarized zone between North and

other as human beings rather than as representations of an opposing ideology.

Park makes few overt missteps in his direction of the screenplay, and those the

viewer does pick up on are in the service of his education as a filmmaker.

The Flick

JSA is divided neatly into three equal

sections. In the first section, Major Sophie Jean (Yeong-ae Lee) arrives in

Neutral Nations Supervisory Committee. The NNSC has been called in to discover

the cause of a minor scuffle across the titular joint security area which

resulted in the deaths of two North Korean soldiers.

As Major Jean

reviews the depositions of the surviving soldiers, the film takes on a Rashoman-esque

structure, displaying the actions that each soldier has claimed took place. The

depositions are not in total agreement. The South Korean soldier, a

well-respected sergeant named Soo-hyuk Lee (Byung-hun Lee), maintains that he

was kidnapped by the North Koreans, and then managed to escape. The North

Korean soldier, Sergeant Oh (Kang-ho Song), swears that Soo-hyuk crossed the

border of his own free will, with the intention of killing the North Koreans.

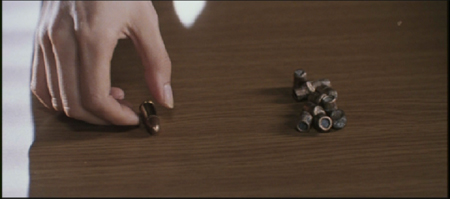

You’re not a man until you can do it with your fingers.

Something

doesn’t match up, so Major Jean digs deeper, uncovering inconsistencies in the

physical evidence. Soo-hyuk’s beretta held fifteen rounds in its magazine;

sixteen shots were fired on the dead Korean soldiers. With the mystery of the

missing bullet as her guide, Major Jean confronts both Soo-hyuk and his

subordinate,

the South Korean guard post.

Here, the

narrative rewinds as Soo-Hyuk recalls the events leading up to the night in

question. The second act is told entirely in flashback, starting at a point

several months before the night of the firefight. Over a series of hesitant

communications, a friendship kindles between Sergeant Oh and Soo-hyuk.

This act

is the heart of the film, the source of all the connection between the audience

and the protagonists. It was daring for Park and the writers to wait for so

long before building that connection, but it works seamlessly. In the first

act, the audience is captured by the mystery; in the second act, they are held

by the interplay between the two friends.

The two

soon become three, as Sergeant Oh’s subordinate starts to feel friendly toward

the capitalist Soo-Hyuk. Then Soo-hyuk brings Private Nam across the bridge to

the North Korean guard post, and the four begin to bond. They play games, talk

about girls, speak idly of their respective ideologies. There was a danger, at

this point, for South Korean Park to descend into propaganda favoring his side,

but there is none. The politics are kept at a distance; the characters are as

uncomfortable with it as the viewers are whenever talk of defection or

political gain is brought up in conversation.

Sadly,

the politics are important, inasmuch as they are represented by the other

soldiers on both sides of the line, the soldiers who see their opponents as

nothing more than enemies, puppets. The friendship, like that of any illicit

lovers, is doomed to fail. The second act comes to a brutal close as the

mystery of what exactly happened that night is revealed to the audience.

Soo-hyuk preferred cat, but this would do.

The third

act returns to the investigator’s frame story, and, again, the transition is

smooth. Now we see much more than simple reticence on Soo-hyuk’s face with

Major Jean asks for the truth. The unlikely friendship between Soo-hyuk and

Sergeant Oh carries with it an odd loyalty, a fragile desire to protect the

other from whatever fallout lies in wait, and a personal sadness that easily

tops that of either Romeo or Juliet.

That’s

not an idle comparison. There is much in the second act that resonates like a

love story. There’s the hesitant first overtures, the long nights of

conversation, giddy playfulness, honesty and occasional mistrust. These men

begin to treat each other like — and call each other — brothers. The third

act divides that brotherhood more cleanly than a guillotine. Except for the

very last shot, there is no reminder in the third act of those fleeting few

months of happiness, and it’s all the more heartbreaking for it. Park spends

enough time with the regret, with the fallout, that it becomes just as real,

takes on just as much weight as the second act.

The

conclusion is a lament for the sense of belonging. Soo-hyuk is unable to live

with himself as a South Korean man, a man defined by his nation. Sergeant Oh returns

violently and irrevocably to his role as an ideological figurehead, though his

motivation for doing so remains ambiguous. Even Major Jean, who develops into a

worthy character of her own, finds out a little something about her history

that puts her objectivity in jeopardy.

The

strands of friendship, torn loose by the night of the murders, remain loose

through the end. Park gives the resolution of the film, especially, an

observational tone; there is no judgment, there is no redemption. I felt that

this was because JSA is focused entirely on the characters, and the actions they

perform. There are no devices of plot throughout the building of the drama, and

so such an external device would have destroyed the ending.

The

screenplay is free of such devices, but the director’s choices betray too much

of a love of gimmickry that undermines some of the drama. Park makes heavy use

of unusual fields of focus, of unconventional camera motion, odd bits of

slow-motion and frame-removal. Many of the scenes feel like a man playing with

his post-production toolbox. Occasionally, these choices are distracting, but

more often they are in support of the drama and easily written off. I’m glad

for Park’s experimentation with the medium; here, it may not work perfectly,

but he has refined his sensibilities since JSA, and one of the results is the

iconic hallway fight in Oldboy. Here, he seems ravenous to

experiment, less deliberate.

The end

result is still a film worthy of respect. It gets downright beautiful at times,

and there’s as much character invested in the moments of tension as there is in

the moments of peace. As a study of friendship, JSA runs the gamut. Maybe

there’s not as much to say on the topic; after all, Park didn’t feel the need

to make a trilogy about this sense of brotherhood. But from the perspective of

this reviewer, there’s not much else that needs

to be said.

8.5 out of 10

"Hang on, you’ve got a bit of cat there…"

The Look

2.35:1

widescreen. The transfer is clean and serviceable. There are many sequences

that take place at night, and the blacks are in good contrast to the brighter

points of interest.

One bit

of Park’s style that doesn’t get overshadowed by his knack for experimentation

is his grasp of framing. He and his cinematographer, Sung-bok Kim, make heavy

use of nature to contain their actors, giving a definite sense of reality to

the spaces they inhabit. Individual shots are certainly beautiful; there is a

sequence in an overgrown field that is both tense and haunting, due in part to

the otherworldly shine that was captured of the moon on the stalks of wheat.

My only

complaint about the look is the occasional distracting CG. There aren’t many

scenes that are CG-enhanced, but those that are stand out like Batman jumping

off a building.

8.0 out of 10

As one, the three soldiers realized that they had each slept with Pvt. Nam’s sister.

The Noise

5.1 Dolby

Surround. The dialogue is presented with two options: English dub, or the

Korean original with English subtitles. I recommend the Korean track, but for

those uncomfortable with reading their movies, the English dub is serviceable.

My major complaint about it (apart from the words not matching the damn lips)

is that the actor used to dub Soo-hyuk has a lower pitch than it seems he

ought. I never got used to it.

The

directional sound is clear and crisp, with a presence that I didn’t expect.

There is a lot of warmth to the soundtrack, the dialogue, and the ambient sound

that makes the whole aural side of things feel full.

The music

choices are forgettable but serve their purpose, including several bits of

classic Korean vocal music. The score is moody and, particularly during the

first and third acts, sounds a bit like a Mark Snow composition for The

X-Files.

7.3 out of 10

Sergeant Oh always wanted to play Dufflepuds.

The Goodies

First off

is an informative set of question-and-answer sessions with the principal actors

and the director. Far from the marketing interviews that we see on our American

stations, these are full of thoughtful questions and reasonably thoughtful

responses, across the board. Of special note is the interview with Park, who

communicates clearly and intelligently, giving insight into his filming

techniques and theories.

There is

a behind-the-scenes featurette that lasts for about thirty minutes. Humor is

well-evident in the filming process; Park seems almost light-hearted, at least

in tone, when addressing his occasionally wayward actors. It’s a good little

feature, with more content than these tend to have.

The

remaining extras are throwaways. There’s the original Korean trailer, which

bills the film as a tragedy. There’s a music video (featuring an indeterminate

performer singing over clips from the movie). There are previews of other

releases from Palm, and there are weblinks to Palm’s website, and to a site for

the JSA

DVD.

5.0 out of 10

The Gingerbread Man, caught at last.

The Artwork

The cover

is dreadfully misleading. The dramatic heads float above a scene that doesn’t

even remotely relate to the content of the film. There are helicopters and

exploding huts on the cover, while there is maybe three minutes of combat

footage in the film itself. Glancing at the cover might make a potential viewer

think he was about to watch a war flick, instead of the cold war character

study he would actually be getting.

And the

tagline’s almost like a joke. "He crossed the bridge of no return."

Well, yeah, Soo-Hyuk kind of does do this, but it’s to play jacks with his

communist friends. How’s that for drama?

2.0 out of 10

Pick it

apart and put it back together, this is a film well worth watching, not just as

a step on the way to Park Chan-wook’s current output, but as a film in its own

right, powerful, haunting, and, unlike yours truly, subtle.

Overall: 8.0 out of 10