Wheelchair rugby. It sounds like a contradiction in terms. The game is played in post-apocalyptic wheelchairs on basketball courts, as squads of quadriplegic smash into each other to get possession of a ball and deliver it to the other team’s goal line. Fast and brutal, the sport once known as Murderball is thrilling and scary. And the guys who play it are profane and funny badasses who, even in a chair, could probably beat the crap out of you.

Wheelchair rugby. It sounds like a contradiction in terms. The game is played in post-apocalyptic wheelchairs on basketball courts, as squads of quadriplegic smash into each other to get possession of a ball and deliver it to the other team’s goal line. Fast and brutal, the sport once known as Murderball is thrilling and scary. And the guys who play it are profane and funny badasses who, even in a chair, could probably beat the crap out of you.

The movie Murderball isn’t really a documentary about the sport, though. It does give you the basics of how the game is played (the most interesting aspect is that each player is given a .5 incremental score based on the severity of their condition – so a player with complete paralysis of all their limbs would be a .5, while a player who has pretty decent use of their arms (and there’s a distinction the film draws, which is that a quadriplegic is someone with some impairment of both sets of limbs – not every quad is Christopher Reeve) will be a 3.5. A team can play up to 8 points in combined value at any one time), but it’s more interested in who these guys are, and what their experience as quads is like.

But don’t think this is some kind of “triumphant cripples” movie – it’s not, and the quad rugby players wouldn’t have it. If these guys are to be looked at as role models – and some of them are – it’s because of who they are, not because of what has happened to them.

Although what has happened to some of them is tragic. Mark Zupan, the star of the film and one of the top quad rugby players in America, became paralyzed after he fell asleep, drunk, in the back of a pick-up truck. His best friend, not knowing Zupan was in the back, smashed it up. Zupan spent 14 hours in a watery ditch, holding on to a branch until someone heard his cries. It’s Zupan’s slow reconciliation with the friend – they hadn’t talked in a decade – that forms some of the film’s emotional core.

The main emotional and narrative core, though, is in Joe Soares. Formerly a star of Team USA, he became embittered after not making the team one year. In what many of his former teammates saw as the ultimate betrayal, he left to coach Team Canada – beating the US in the World Championship at the beginning of the film. The movie follows the rivalry of the two teams as they prepare for the Paralympics, where they face off again.

Joe’s homelife is fascinating. On their anniversary his wife toasts, “To us.” “To Canada,” Joe replies. They live in Florida, to put it in perspective. Joe’s son is a doughy nerd (in a scene that is easily among my favorite in the history of cinema the documentary filmmakers interview a bully at his school, and the kid says – on camera – “Yeah, I tore pages out of his book, and I’ll do it again if he steps out of line!”), and the reversal here, where a disabled dad is annoyed that his son isn’t more physical, is fascinating.

There’s also the parallel story of Keith Cavill, a biker who is recently paralyzed. It’s through his eyes that the filmmakers introduce us to what reality is for a quad – including instructional videos on how to have sex. Yes, many quads can have sex, and the ones in this movie have hot girlfriends to prove it.

Keith’s experience is heartbreaking. We’re there when he first goes back home after months of rehab. Everything he ever took for granted in his home is now changed as he is stuck in the chair. But then you look at the film’s other quads, who have had years to get used to their disability, and when you see Keith’s eyes light up when introduced to the sport you see his future.

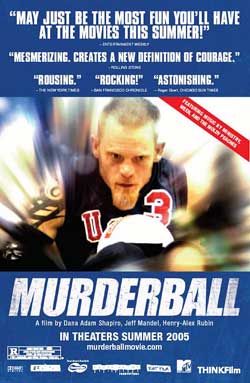

The movie’s damn funny, too. These are hard drinking, fun having guys and they crack wise and obnoxious throughout – just like any athlete. The great documentaries bring you completely into another world, and directors Henry Alex Rubin and Dana Adam Shapiro do just that – we’re immersed into the sport and the players’ lives. What’s most rewarding, though is how strange and unknown this little subculture is. The film is really exploring something just left of our normal reality and it’s easy to get sucked right in.

The triumph for Shapiro and Rubin is how they’ve crafted a narrative strong enough for a dramatic feature. Hell, I would be shocked if this thing hasn’t been optioned by now – with the rivalry between Canada and the US, the personal aspect of the disdain between Soares and Zupan and the redemptive aspects of Zupan’s relationship with the guy who was driving that truck, this is Oscar winning territory. Hell, Soares looks an awful lot like Robert Duvall, so I’ve already got you started on casting.

The thing is that I don’t think Hollywood would know how to approach this without cloying sentimentality. Because Murderball is willing to look at all sides of these guys – the inspirational as well as the assholish – we get reality, and reality is the antithesis of sentimentality. That isn’t to say that the movie isn’t affecting – I will cop to some tears towards the end – but that emotion is earned and true, not some gross manipulation.

Murderball, in its 88 minutes, did more for my understanding of the disabled than anything else in my life. On top of that it managed to get me excited about a strange new sport, and that’s not something that happens to me every day. Murderball isn’t just one of the year’s best documentaries, it’s one of the year’s best movies period.

9.2 out of 10