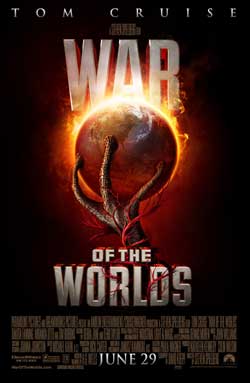

When you’re talking about CGI you’re talking about ILM’s Dennis Muren. From the earliest CGI work, like Young Sherlock Holmes, to War of the World, Muren has been at the forefront of the special effects business. And he doesn’t just do digital – he’s been doing effects in films longer than some of you have been watching them, and his work on movies like Jurassic Park and the first five Star Wars have made him the only FX man with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

When you’re talking about CGI you’re talking about ILM’s Dennis Muren. From the earliest CGI work, like Young Sherlock Holmes, to War of the World, Muren has been at the forefront of the special effects business. And he doesn’t just do digital – he’s been doing effects in films longer than some of you have been watching them, and his work on movies like Jurassic Park and the first five Star Wars have made him the only FX man with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

He was the first person I spoke to at the junket. He was originally going to give a presentation to the press, but that got scrapped at the last minute. Instead Dennis joined the circuit of roundtables in the Grand Ballroom of the Essex House Hotel on Central Park West, where he spilled some secrets.

This interview contains what could be considered spoilers. While I don’t think there is anything here that will ruin your enjoyment of the film, be warned in advanced if you are staying spoiler free.

Muren: I think they were talking about showing a scene here. It might have been the ferry boat. I think they decided they didn’t want that running in the background.

Q: So how did you do it?

Muren: It’s all real. I guess that’s all I’m supposed to say. There are no effects or anything in it, we just tipped a real boat over. We lost some people, I’m sorry but…

Q: How much is digital?

Muren: There was a lot of work in the show. A few hundred shots. But the idea that we were trying to do is present it from the point of view of a working man. So it’s not a typical Hollywood movie where you’re looking at New York, you’re looking at London, you’re looking at Tokyo – it’s all from the point of view of this guy in his neighborhood, which means you only see what he sees. The shots that we’ve got to do are designed different than a regular movie – they’re all done documentary. We looked at the 9/11 footage people shot, at a lot of war combat footage. You’re surprised because something just flies in from the side of the frame that you didn’t know about. That was Steven’s direction, and I encouraged it. It makes the effects a lot harder, but it makes it a lot more interesting to look at the movie because it’s different. It’s not like a regular movie where you see it from a lot of different views and you can figure it out, you only see it from Tom’s point of view.

Q: How many people on your staff?

Muren: We started at 60 and in the last month we were at 175 or so.

Q: How much input did you have in the actual design of the alien ships?

Muren: We designed them. ILM designed the alien ships and the aliens themselves.

Q: What were they based on?

Muren: We didn’t quite know. Everybody reads the book and they have different ideas about these walking tripod creatures, which weren’t done in the [1950s George Pal] movie. It was because they didn’t have the technology to do it. Now we have the technology. We looked into it, and Steven definitely wanted tripods, but he didn’t want them to be clunky. We did over a hundred designs, some of which were very insect-like, some of which were very stiff walking machines, some of which were very blocky, like large pieces of concrete. So they would look very, very strong. But we ended up with what’s in the film, which is a combination of things, which is actually very sinister looking and yet invincible. We wanted it to look like an invincible killing machine. And compelling to look at, so that when you see it in silhouette up on a hill it’s interesting and you want to look at it. But you don’t know what’s going to happen to you and you know this thing could wipe you out.

The point of view of it is the way that – whenever any kind of attack goes on where a high end civilization invades a low end one, and that’s gone on all through history, usually the people on the bottom who see the invaders coming have no clue what the armament is. They don’t understand the language of the invaders, they can’t discuss it with them – “We’ll give you our land!” They just attack. That’s the point of this. We wanted them to look like that, they’re there the attack you but you can’t fight them, you can’t even talk to  them. You don’t know what kind of machinery they have, what weaponry they have.

them. You don’t know what kind of machinery they have, what weaponry they have.

Q: Speaking of the invaders, we see the aliens briefly. Can you talk about the design of the aliens?

Muren: They look ugly and creepy, but we didn’t want them to necessarily look scary. We just don’t understand them. To them they look OK, to each other. We look weird to them. They’re here to conquer, to take over, it’s part of their job. We followed something that I believe is in the book, which is that everything is in threes. The tripods are on three legs and the aliens themselves are on three legs. They have three fingers, and viewed from the top they have an almost triangular shaped head. Same with the war machines. So we sort of carried that through. We tried three eyes but that looked too weird.

They’re trying to look strange, we wanted something you hadn’t seen before but not a monster. We didn’t want that at all.

Q: Why aren’t they from Mars this time?

Muren: We felt that wouldn’t work today. Too many people know what’s up there now. They’re just from out there somewhere – which in those days, the 1900s, people thought that Mars was way out there.

Q: What was the most challenging shot for you?

Muren: The biggest sequence for me was the Newark sequence at the beginning, where the ground opens up and the buildings sort of shred. Doing all that. The approach I took to the film was not to use too much blue screen, if any at all, so we shot it on the real locations. It left Steven to be able to direct it as if everything was around him – and he’s good enough to visualize that the building over there is now leaning this much to the left. The actors can do that rather than go back to LA and do it in front of a blue screen, which is tough on everyone. But the effects are pretty challenging because it makes our work harder, but there’s a reality you don’t get if you break it up into parts and shoot several elements at different times.

Q: Do you think that there’s a backlash against blue screen and heavy CGI use? Do you think the pendulum will swing away – more blowing up real buildings?

Muren: I think it’s leveled out. Things haven’t changed much in the last three or four years. It’s found its level, and a lot of it’s budget – everybody wants to blow up the real buildings. Directors want to do it because they can put more cameras on it, but it’s too expensive. You can’t do shots like this where you’re actually driving down a real street – which is obviously real, and not a backlot – and everything is blowing up and people are dying… there’s no way to do that full size.

What we’re missing, from an effects point of view, is that there’s too many movies coming out that don’t look real. That’s a product of there being a lot of people getting into the business now who don’t know what reality is. They’re copying special effects, they’re not copying reality.

Q: I ask because on the one hand you have Robert Rodriguez doing Sin City almost completely CGI and on the other Christopher Nolan trying to do as much of it practically as possible on Batman.

Muren: It depends on the director. Christopher Nolan can go into real environments and do stuff, he’s trying to get the proper performances out of the actors. He wants to get them in the zone, in that mood, and it’s tough to do in front of a blue or a green screen. It’s harder. Although Robert says that the actors really got into it. But on that film it’s a noir film, so it’s easier to jump in – and they had the comic book, so they could always understand what’s going on.

Q: You said that people getting into the business now aren’t as familiar with reality, but do you think it’s also possible that a problem is that audiences are more sophisticated and know what’s digital when they see it?

Muren: Maybe. I’m not so sure. I think it might go the other way, where people are used to games and so it’s OK that it doesn’t look quite real. But maybe looking like a game brings it too much into their own home, and I’m not going to pay 10 dollars to see imagery I could see at home. I don’t know. There’s some incredibly realistic stuff being done now, maybe the whole bar has been so raised that it’s harder to make it look really real.

We’re always pushing ourselves. When I’m done with a film, I always assume that work is obsolete and I try to figure out what the audience will want to see next time. And this had all the problems – bright daylight, handheld shots, long shots that go on for a while and right at the end of it some effect happens. As opposed to, in some movies, the entire shot would be an effects shot and look kind of off so that at the end something could happen.

Q: How many effects shots are there in the film?

Muren: Three or four hundred. There’s other stuff in there – we have under 300 visual shots, but there’s other stuff like pyro going on. We did a lot of miniatures. Our work isn’t all CG at all. The tripods are all CG,  but a lot of the explosions and buildings blowing up – we just blew up parts of buildings, not whole buildings, and put those in the shots.

but a lot of the explosions and buildings blowing up – we just blew up parts of buildings, not whole buildings, and put those in the shots.

Q: What is it like to work with Steven as a director? Is he there with you every day?

Muren: I’m there with him on the set. Either me or Pablo Helman, who is my associate supervisor. This show was so rushed that we had to have two supes to get it done on time and keep the quality up. We communicate with Steven by a video conference of some sort – satellite or T1 line or whatever we can get – at least 2 days a week, and the last three weeks every day. So we talked to him 45 minutes a day and show him the stuff. But I’ve worked with him so long that I kind of know what he wants, and I know the intent of what he wants. A shot exists for a reason, and that’s completely different than if you look at the shot. You have to direct the shot for the point of view of whatever story the director is telling, and I know the story Steven is telling, so it’s very important that each shot not just be a shot on its own, but that it be a part of a whole. If something falls apart it’s important that it not just blow up but that it crumbles in an interesting, aesthetic way. He’s a very aesthetic person.

Q: You say that you know what he wants. Are there ever times when you think you know what he wants and you’re wrong?

Muren: Not very often but sometimes. Nobody knows the story like him. I may have 200 people running down a hillshide and he’ll want 400, and I just thought 200 was enough. But he looks at it and he knows that at that moment in the movie he needs more than 200, because he knows the whole story.

We were working right up on the shot of all the people running down the hill that you see at the end of the ferry sequence. The tripods are coming over the hill and they’re shooting all these hundreds of people… that was a difficult shot because we had to show the tripods destroying people, people turning into that dust, and their clothes flying up in the air from the explosions so that a couple of shots later the clothes are coming down through the trees. That’s an awful lot of things to get into one shot – tripods appearing, people running, it’s nighttime, it’s raining, there are all these puffs of people blowing up, clothes are falling. That was just tough to try to get that to even read. Looking back at it, it would have been nice to have one or two more shots in there. But we were working on that right up to the very end.

Q: When did you finish the last shot?

Muren: Probably about a month ago or so. We’re in June now? It was May, May 15th.

Q: How did you guys decide to have people turn to dust?

Muren: We didn’t want it to look like every other movie you’ve ever seen. We didn’t want fireballs there. I was there when Steven came up with that idea. He said, “What if they just turn to dust, and their clothes go flying up? And then we could have the clothes falling down in other shots.” That’s just genius. Where that came from – when he said that, when he talked about the clothes falling, I thought, “Oh it’s people’s souls.” What a great idea. But I have no idea where it came from. But it did come somewhat from not wanting to show what other movies have shown.

What we were doing was trying to make it look different. We didn’t want it to look really super contemporary and slick looking. We wanted no laser blasts coming from these things. They have a little more textured rays. The machines aren’t slick, smooth chromium – they’re more armor plated, almost 19th century machines. They’re more gritty. They’re more harsh looking.

Q: Going back to the dust, I was struck by how that relates to the 9/11 imagery of people covered in dust after the towers collapsed, and that some of that dust was… well, people. When you’re making a film like this, which has wholesale destruction on that level, how does that work in a post-9/11 world?

Muren: We try to copy reality as much as we can. Once the audiences sees it, they know it. And it’s true for us too – once we see it, we know it. We had never seen anything like that. I would never have guessed in a million years that the Twin Towers would have fallen the way they did. I never anticipated that. I thought they would fall over. And that, I think, is what bin Laden was expecting, too. That’s why the planes hit from both sides. It was what he was trying way back in 93 with the bombing.

It makes our work harder, because you’ve seen the reality. But as much as we used that stuff, we used combat footage too. Things come in from the side of the frame where you can’t see it. If you’re an individual looking, like Tom’s character, that’s all you can see. In a typical Hollywood movie you would show the battle and then show Tom looking and ducking, or whatever. We tried with a lot of the stressful shots to make things unexpected. Which gives it a lot of energy.

Q: In the basement scene, when the camera/eye thing comes in and snakes around, was that a nod to The Abyss?

Muren: You know, somebody reminded me of that and I thought, wait a minute, that’s in the book! And did Jim get that from the War of the Worlds book? It’s also in the [1950s] movie.

Q: But just even in the way that it moves, it was sort of the evil version of the psuedopod.

Muren: I did that too, but it wasn’t intentional.

Q: How rushed were you, and how much did it affect you?

Muren: It was tough, but as long as I know in advance I can plan for it. We knew in September what was coming, so we just geared the crew up. That’s why I put another supervisor on the show. We had 179 guys for the last three or four weeks of the show. For us it was OK. As long as we can get feedback from Steven, and he made himself accessible.

Q: Were there things you would have done differently if you had more time?

Muren: Probably. We could have had more shots in the show. There are a few shots here and there I would have liked to work more on. But most of the work I’m pretty happy with.