These articles are from a series of pieces I wrote back in 2008. I’m porting them over to CHUD for reference since I’m also in the midst of a week of non-Godzilla kaiju films.

Godzilla Raids Again (1955)

I’d never seen this particular chapter in the green guy’s history, as I think the films that played most often on TV when I was a kid were the color kaiju movies from the 60s and 70s. This entry from 1955 seems to have served as a bridge between the mostly somber and straight-faced atomic bomb allegory of Gojira and the more psychadelic, pure entertainment of Godzilla films that came later. Raids Again introduces Godzilla’s first kaiju nemesis in the form of Anguirus, a kind of big spiky turtle-like creature that looks a bit like a cross between Gamera and an Ankylosaurus. As a first giant monster opponent, Anguirus is an odd choice because he’s not bipedal like Godzilla, which would have presented the production crew with a whole new set of challenges on the set. Since giant monster-on-monster fight action is what propelled the kaiju genre, Godzilla Raids Again seems to have a pretty important role in kaiju history by way of its introduction of monsters battling other monsters.

This is an interesting film in that it tries to remain somewhat grounded in reality and it still focuses on the human characters, while it obviously begins to open up a world where Godzilla himself becomes a hero. It maintains some continuity as characters discuss the way Godzilla was dispatched with the Oxygen Destroyer, but it also opens the revolving door for an endless stream of Godzillas that can be destroyed and then reborn or replaced. I’m still on the fence about this. Godzilla wouldn’t have nearly the pop icon appeal if he was always just a destructive manifestation of mankind’s hubris, but there’s something about rooting for the giant beast that is stepping on people that seems wrong when you consider the creature’s origin.

There’s a wonderful depth to Godzilla as the metaphorical doom brought about by the atomic age, but that kind of depth only works if the monster remains threatening. In later films, Godzilla is clearly the hero, and he’s more or less protecting the earth from other monsters, or at least fighting them off in a way that benefits humans. Cloverfield played a bit with the idea of a monster stomping on New York as a symbolic reminder of September 11th, and while it didn’t do as much with that connection as it could have, the idea was clearly there. These giant monsters are flat out silly in a lot of ways, but they give us a good chance to see the effects of large scale destruction and devastation through an easy-to-stomach allegory. A kaiju film that served as an allegoy for ethnic clensing, violence in places like Darfur, the repression in Tibet, or even the US government’s pathetic response to events like Katrina could all work. We need these movies sometimes to remind us of the human toll; to show us that when a monster’s tail takes out a whole building, there are dozens or hundreds of lives crushed and irrevokably changed in an instant.

Godzilla Raids Again might be seen as the point at which the kaiju films began to lose some of their allegorical power, but it also reminded me that these films used to try to balance the entertainment with a conscience. For old, slow-moving, black and white Godzilla, I still prefer the original but this one had a nice expansion of scope and never strayed too far into farce.

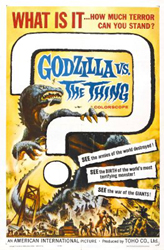

Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964)

I feel like I must have seen this movie a dozen times or more, but in fact I’m sure that I’ve never sat through the whole thing. Some of the imagery is remarkably close to footage from Mothra, and some of it wound up in a black and white Super 8 reel that I have, so it has a kind of familiarity but watching it now made the whole thing seem very new.

Mothra Vs. Godzilla builds on the template set out by Godzilla Raids Again by pitting the king of the monsters against another giant foe, but this time, Godzilla is clearly the villain. Carried over from Mothra’s origin story in her own film, the giant moth monster is once again represented as a benevolent and naturally peaceful creature tied to the peaceful natives on Infant Island. While the natives and the little pixies that sing to Mothra aren’t quite as psychadelic and out there in this film as they are in the original Mothra, it’s interesting to see how their look derives from a blend of Polynesian and Ainu motifs.

Also interesting was the theme that this film built off of. While it threw in enough jabs at nuclear experimentation to keep that idea running, the major plot and conflict for the human characters in Mothra Vs. Godzilla is one about trust. From the fishermen and businessmen who initially find Mothra’s egg at sea and screw each other over trying to make a buck from it, to the modern Japanese asking the tribal natives of Infant Island for help in spite of their comrades’ obvious attempt to cash in at Mothra’s expense, the whole film winds up being about people trusting other people. It’s a relatively thin and obvious morality play, but these weren’t movies made for adult audiences to deeply analyze. The fact that the series tackles an idea outside of the danger of atomic/nuclear experimentation is proof enough that the films aren’t simply throw-away cheese.

While the theme music used in this film is probably my favorite of any of the kaiju films I’ve seen, it defintiely felt like there wasn’t enough time to write a full score, as the same theme plays over and over and over again. This movie also employed a more obvious use of sped-up monster footage to keep the lumbering beasts from looking like people and pupeteers struggling to fight on a soundstage. In one respect, I love that the sets and models and scale version of everything are very easy to detect because those elements lend these movies some charm. However, much of the battle between Godzilla and the Mothra larvae takes place on a desolate island where there’s not much to give the monsters a sense of scale. While the set and repeating theme render the battle scene a little tedious, it’s still fun to watch Godzilla fail to deal with two worms that are much smaller than he is that have really only one power.

Mothra Vs. Godzilla was an obvious attempt to cash in on the power of two monsters who’d each had their own features, battling to the death in a single film. I think that the analog today might be something along the lines of Alien vs. Predator, and when I look at this film in that light, I see how easy it is to dismiss it. Still, it’s hard to be so cynical about these movies because they seem to always know what they are, and who they are for. The series may never attempt to get back to its more serious origin in Gojira, but this installment makes for an entertaining and at least partly thoughtful romp that works well with both the Mothra and Godzilla mythos. It explains how Mothra can live forever through a cycle of death and rebirth, and it begins to give us unexplained Godzilla returns to set up the idea that Toho isn’t going to worry about HOW Godzilla keeps coming back–they just want you to know that he will.

King Ghidorah the Three Headed Monster (1964)

By late 1964, Toho had already established Godzilla, Mothra, and Rodan in their own movies, so to keep the series going they came up with a new monster that was enough of a badass as to necessitate a giant monster team up. King Ghidorah, the three headed dragon kaiju who is born out of a strange meteorite that has crashed to Earth is indeed the fiercest and biggest of the monsters, and Toho did something pretty remarkable in bringing him to life. For Ghidorah, the typical rubber suit is augmented by pupeteers who work the three heads, wings, and twin tails so that the monster is always moving. Since all of the monsters have a signature lok and sound, it must have been a challenge at this point to create a new beast that was significantly different as to be instantly recognized in posters and trailers and huge battle royale scenes, but Ghidorah is a real triumph in monster design.

The story follows a brother and sister team (a common theme in these films, which is antithetical to the American notion that every leading adult couple in a film has to share a love story,) who get wrapped up in the mysterious disappearance of a princess who reappears claiming to be from Venus. The Venusian’s predictions about bad things happening and monsters appearing start to come true very quickly and the film is off, with a carload of gangsters out to kill the princess, the brother who’s taken on the assignment to protect her, the sister who wants the princess’ story, and of course the pixies from Infant Island who will eventually be called on to ask Mothra for help.

There’s franky not much new in the story of King Ghidorah, and most of the film feels like little more than the necessary machinations to introduce a new monster and a giant battle. As a fan of the genre, I don’t really mind that, but I can see how this particular entry in the Godzilla series might not excite a lot of people. The film spends almost no time on any of the allegorical themes that made the genre interesting, and it instead seems to use nondiscript characters to fill the perfunctory roles of scientists, reporters, and military men.

If King Ghidorah himself wasn’t such a cool character design, I don’t know that there’d be much in this film to warrant repeated viewings. The battles get a little tedious and the human story lacks an emotional core that might otherwise keep it interesting. Maybe the producers knew that they had a good thing but not necessarily a great movie in King Ghidorah, since nearly the same cast of characters would show up just a year later in Invasion of Astro-Monster, a film that put a new spin on all of this and wound up as one of my favorites of this era.

Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965)

For my money, Invasion of Astro-Monster is the high water mark for this classic era of man-in-suit kaiju films. While the team up of Godzilla and Rodan against King Ghidorah is a complete rehash of the monster conflict from King Ghidorah, the rest of this film offers something funky and new to Toho’s formula.

The film starts off by announcing a complete disregard for logic and rules of the real world by stating that the action is taking place in 196X. We quickly see a manned rocket mission from Earth on its way to Planet X (actually a moon of Jupiter,) where the duo of an American and Japanese astronaut are sent to explore a newly discovered world. It’s about here, five minutes into the film, where things stop making any real sense. The scientists explain that they are only now able to see Planet X because their telescope technology wasn’t advanced enough before which speaks a little bit to the idea that humans in this world have to deal with realistic limitations. Then we see the two astronauts landing their rocket ship and venturing out onto Planet X and we’re supposed to buy that mankind lacked the technology to even see Planet X a few years ago, but that we’re perfectly capable of sending a couple of guys there in a matter of hours.

Of course, Planet X looks a lot like the moon, but it turns out to be inhabited by a race of odd and stiff humanoid aliens who have been forced underground by the destruction of Monster Zero. We soon come to learn that Monster Zero is the same beast that folks back home know as King Ghidorah, and the astronauts get to watch Ghidorah going to town on the Planet X terrain via a video screen. As the Planet X leader explains in his mechanical monotone, Godzilla and Rodan go by different names on Planet X, specifically Monster Zero One and Monster Zero Two. Okay, really? Not just Monster One and Monster Two but Monster Zero One and Zero Two? Is there any way that makes sense?

The plot is kicked into gear when the astronauts are sent back to Earth to ask Earth’s leaders if it’s okay for Godzilla and Rodan to somehow travel to Planet X to fight off Ghidorah. Nevermind that no one has really ever come up with a good way to find or talk to these monsters, the astronauts figure it’s worth a shot since the Planet X guys are offering a tape with data about how to cure cancer in return!

Invasion of Astro-Monster is just willfully silly as it mashes up the kaiju tropes with American 1950’s Sci-Fi imagery straight out of Plan 9 From Outer-Space (although in this world, maybe it would have been Plan Zero Nine.) The aliens fly in iridescent saucers and they shoot ray guns, while Earth’s mightiest model Jeeps, tanks, and rocket launchers are typically useless when aimed at giant monsters. I love it. It’s as if the world forgets what works against these monsters after each encounter, and they are always mobilized to come up with a new strategy for thwarting or fighting off Godzilla and his pals. At least this time they ask the Association of Housewives for advice (and I’m not making that up!)

This film epitomizes all of the cartoonish fun that that these films can be by throwing so many ridiculous plot elements at the screen that the audience has to just laugh through it. On the human side, there’s another brother/sister dynamic, a romance between the American astronaut and a Planet X spy, and a nerdy inventor of a device called the Lady Guard that looks like a compact but winds up being a kind of personal alarm device. On the monster end of things, Rodan and Godzilla get to square off against King Ghidorah, and Godzilla breaks out into a bizarre kind of kung-fu leprechaun dance when they defeat their foe. During the film’s climax (and honestly, the last 30 minutes all feel like one big climax,) the monsters fight each other and the humans fight off the aliens (whose intentions, it turns out, were to use the monsters to conquer Earth to get some water) with what can only be described as a precursor to the Minmei defense!

And yet in all of this, and maybe I’m reaching here, is the return of the symbolism that made early Godzilla films so resonant. While the film isn’t concerned with milking the atomic bomb/nuclear threat story much more, the role that technology plays here is key, especially the idea of the computer. The Planet X aliens get all of their instructions from some unseen computer that has essentially turned them all into carbon copy automatons. It’s the classic fear of losing the self to the cold world of machines that underpins the human drama in Astro-Monster, and that’s a theme that not only picks up where the atomic bomb left off, but winds up being fairly prescient of a large swath of future Sci-Fi films. Ultimately, it’s a man-made piece of technology that saves the day, so the film doesn’t stick to a hard line about technology the way something like Terminator wants to, but the underlying premise is there and it reminds me that these movies, as silly as they are, can still work on multiple levels.

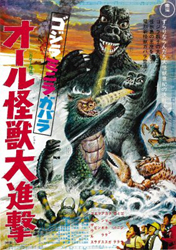

All Monsters Attack (1969)

All Monsters Attack (also known as Godzilla’s Revenge) is undoubtedly the strangest kaiju film I’ve watched as part of my Godzilla Madness program, as well as the most deceptively advertised. Rather than focus on a giant monster melee or Godzilla actually raining down revenge on anyone, the film is centered on a little boy named Ichiro, and it tells the tale of his blossoming from a wimpy crybaby to an obnoxious jerk like the rest of the bullies. I knew that this was going to be a different kind of monster movie from the funky mod song that played over the title sequence, but I wasn’t prepared for the film to be a morality play about how you should give in to peer pressure to become a nuisance.

Ichiro is a latch key kid who is smaller than the other kids from school, who’s best friend is a girl (icky), and who dreams of escaping away to Monster Island. The only way that I can explain the way that last bit works is to rationalize that All Monsters Attack does not take place in the same universe where the events of Godzilla really happened. Since the only time monsters appear in this film are in Ichiro’s dreams and imagination, I can only conclude that Ichiro lives in OUR world, where Godzilla is a cult hero, action figure, and movie icon. How else could anyone ever make sense out of a film series where the central character goes from being a manifestation of our fears and guilt about the atomic bomb to a corny father figure showing young Ichiro how to fight off bullies?

All Monsters Attack illustrates a funny point about popular movie villains that seems to be true over and over again. Any villain that’s significantly well-designed and represented in a series of films eventually goes from being someone that the audience is terrified of to someone that the audience roots for and and wants to see on a t-shirt. Darth Vader. Jason. Freddy. Hannibal Lecter. These characters epitomize the villain, they are often embodiments of evil, and yet they usually become the main selling point of pop cultural empires that appear on the surface to be about good triumphing over evil. While Godzilla always had the potential to be cheesy, I have to admit that I never thought I’d see him training his son Minilla to breathe fire as a way to teach a sissy kid how to stand up for himself.

The bully storyline is interesting too, because it reflects a theme from one of my favorite Japanese movies, Tampopo where another undersized kid has to learn to stand up for himself with the help of a surrogate father figure. I find the way that these two films handle the bully story to be opposed to the way that classic set up is usually handled in American narratives. Over here, the moral is almost always that fighting and violence won’t solve anything, and that there are other ways to stand up to a bully or that fitting in with the bully and his crowd aren’t important in the long run. Often the American version of this story ends with a kid having to beat the bully despite his best effort to avoid confrontation–the same way that a villain in an American movie often gets his comeuppance in a final desperate act of self-defense on the hero’s part rather than as a natural consequence of the climactic confrontation itself. I was surprised that Ichiro’s journey was scripted to end with his beating up of the bully, but I was even more surprised that he then skipped off and joined the bully’s gang! If that wasn’t bad enough, I moved from being surprised to being shocked when the adult antagonists in the film repeatedly admonished one another with shouts of ‘God Damn!’ I thought this was a family film?

This 1969 entry to the classic kaiju era was supposed to be a film for kids that capitalized on Godzilla’s growing popularlity among younger audiences. I shudder at the thought that those audiences were leaving the theater thinking that the best way to deal with a bully or a gang of prankster kids was to become one. I’m not sure that the same morality play would have ever floated in the US, but I guess this film WAS released for American audiences, and in fact it’s one that I think I’ve probably seen parts of on television more than any other. After the sublime monster goodness of Invasion of Astro-Monster, it seems like the Toho clan was running out of viable ideas for Godzilla, and as a result this film winds up falling between the cracks as being too juvenile for older audiences, but oddly inappropriate for kids.

Godzilla vs. Hedorah (1971)

This installment from the classic Godzilla era is easily the most gleefully ridiculous Godzilla film that I’ve yet seen. It was released in 1971, which goes part of the way towards explaining the hippies, go-go dancers, acid rock band and environmental theme, but this movie has to be more than just a product of its time. In the same way that Super Mario Bros. gave many westerners their first glimpse of the zany, dayglow side of Japanese culture, Godzilla vs. Hedorah is a great example of the Japanese penchant for non-sequiter humor and blissful disregard for coherent storytelling.

The movie follows a young boy who is himself a Godzilla fan as the Japanese countryside is attacked by a giant smog monster made up of toxic pollution (with eyes!) Clearly the morality play has shifted in this installment from a warning about mankind’s technological hubris to a warning about our destructive impact on the environment, but that shift actually feels pretty natural after years of monsters who exist for no other reason than to remind us of the dangers of splitting the atom. Hedorah does an amazingly good job of serving as the symbol of environmental devastation, and while the movie is never subtle it its tale, the monster is for once at least considerably disgusting and threatening. Unlike Gigan, Ghidorah, or Mothra, Hedorah is a beast that it’s really just about impossible to root for. Also unlike those other monsters, Hedorah is seen not only flying over and wrecking cities but affecting flowers, plants, and individual people who are running around trying to escape. Usually the devastation has a grander scale, but some of this film’s most shocking scenes involved individuals being scarred or melted to the bone by Hedorah’s sulfuric acid exhaust.

While the battle scenes make up a large part of the running time (and they do drag,) the rest of the movie is stitched together from relatively little narrative. What holds it all together are these weird cartoon interludes, scenes in a swinging nightclub, and inexplicably stylized shots of pollution and of people reacting to Hedorah. This was the first Godzilla film that made me laugh out loud several times and I had to stop often just to make sure that the film was really going in the places that it seemed to be going. It would be easy to chock all of this up to the era in which the film was made, but in fact, there were movies made just before and just after this one that weren’t quite this weird.

Just when I thought I had seen all that this series in its classic incarnation had to offer, I picked up Godzilla vs. Hedorah and I realized that while some of these films (ok, most of them) were derivative to a fault, the series continued to be fertile creative ground for people who wanted to entertain audiences. I only wish that this film was part of the Godzilla Classics collection, as I’m now going to have to buy this DVD separately to hold on to all of this crazy.