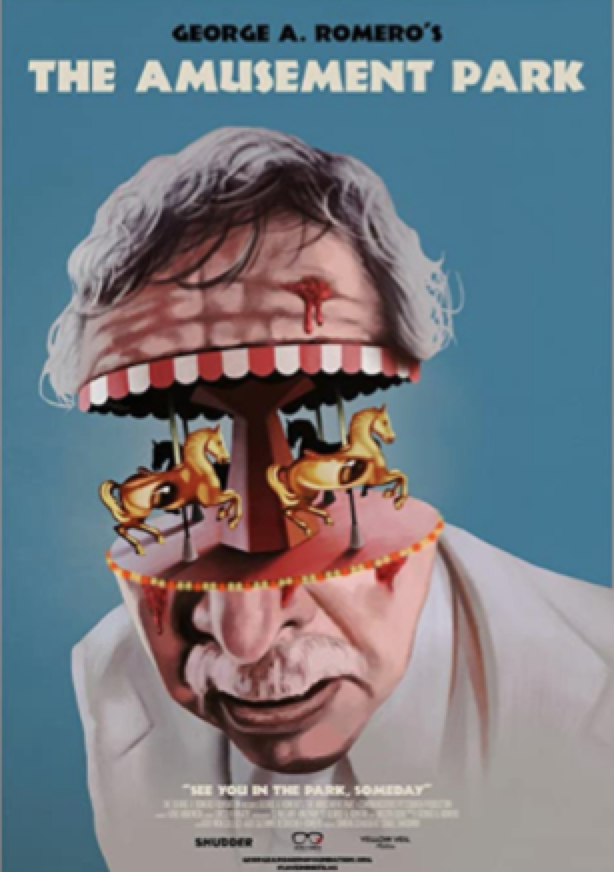

THE TRAILER

THE DIRECTOR

GEORGE A ROMERO

THE ACTORS

Harry Albacker, Michael Gornick, Lincoln Maazel, Jack Gottlob, Phyllis Casterwiler, Halem Joseph. Marion Cook

THE STORY

The Amusement Park is a nightmare about the many old-growing indignities. Whether it’s suffering from a bumper car crash or being accused of it because they speak to young people, an older person in a white robe (Lincoln Maazel) attends an amusement park with other senior citizens where tragedy strikes after a disaster. The Night of the Dead Living lasts 52 minutes. An appeal to compassion, the writer’s figurative horror show evokes a sense of the ugly nature of life at the twilight of our lives, where indifference and brutality reign.

THE RUNDOWN

Romero never was interested in criticizing anybody gently. ‘The Dead’s Dawn, ‘Monkey Shin’ (1988), ‘The Dead’s Country’ (2005) in particular, and his most recent movie ‘The Survival of the Dead’ (2009) wasn’t long overdue waiting to see whether you caught on. They are beginning by attacking the US Army, the rich, corrupt government, and the systemic deprivation of the rights of Americans of the poor and working class. “The Amusement Park” clamps down on her hero’s neck and rejects healing, like the “The Crazies” that reconstituted Vietnam’s War in a suburb of Pittsburgh the same year. No matter what the Luthern think they paid for, at the height of his fiercely declining morals, they inadvertently released our most cynical painter to the declining morality of the nation.

Lincoln Maazel, the pious grandpa in Romero’s ‘Martin’ (1978) who opposed the main character, opened the movie to direct speech. He walks across the open, rain-slicked park about how, at your age, you are reduced to an abundance of services and possibilities until there is no room for the old. Utilizing a show, Maazel will lead us to The Fun Park, which, despite its carnival, seems a lot like the outside world.

In a pristine white suit, Maazel, cheerful dapper, enters a vital, antiseptic waiting area with just a few seats and a sad, lonely face and respiratory hemorrhage. Maazel invites this guy to walk with him outdoors. “Nobody’s out there. You won’t like it!” manages the wounded guy between gasping sobs. Maazel begins his day at the park Undeterred. Before he gets money in exchange for tickets, the ticket holder must be stopped from low-balls seniors out of their precious belongings as if they were a crooked antiquarian. All the signage does not show the park’s characteristics but reads as if you had concerns about an insurance form or medicine cautions. On Halloween, Maazel takes a miniature train ride that turns scary when individuals start appearing aboard the train. There seems to be nobody else noticing them.

Even when the old-time vehicles strike the bumper and see a collision, something extraordinary is underway. They eloped and treated each other like a snub, an elderly lady, and a young guy, so much so that they might get a policeman involved. While Maazel attempts to testify, the policeman reports in his records that he should use spectacles. How could he have seen anything without them? He thoroughly humiliated the younger driver’s noises that the old should not be let on the road leave the collision scene.

Unfortunately, as things were till now, without any warning, they jackknife in the nightmare. His meal was destroyed by the fact that a rich man asked his table to be moved so that he did not have to look at his hideous vittles eating the most diminutive moneyed boss. He watches over a fortune teller to show a young, loving couple what they are supposed to be—pest and panic. In some stupor, the park empties except Maazel, then several motorcyclists appear to beat him and loot him. He attempts to look for medical care and gets band-help and a pinch-off. He is broken eventually by trying to join the picnic of a young girl, and she is quickly packed up with her mom, forcing her to go, reading a tale to her. He sees a dreadful crescent walk the park, and a clutch of customers drive him away with murder in their eyes from the freak show. Suddenly it does not seem so awful in the antiseptic white room.

Romero’s favorite movie was “The Tales of Hoffmann” by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Romeo, interviewed by Robert Elder, told us, “It was movies, fantasies… It was everything. And it early gave me a sense of the power of the visual medium — the idea that you can play with it. He did all his stunts on the camera and was some evidence. But it worked.” It was transparent. Romero never relied much on the technique he had seen at the filmed opera of Powell & Pressburger. The work that turned him to the camera would inspire little emblems, such as the white face of 2000’s “Bruiser” anti-hero, or the magnificent comic books of its homage to the EC Comics, “Creepshow” (1982). It always appeared as though the pupil with an apparent master never had a workout like his passion for Powell & Pressburger. until the Amusement Park had dismantled it. It was not enough. The film is designed to put the hero against an unearthly array of opponents in strange vignettes from “The Tales of Hoffmann.” The Amusement Park is the only one of Romero’s movies that intentionally seems episodic and does not lose its whole line. Everything conspires against Maazel in the aesthetically stunning “The Amusement Park” to make him feel soothed, unwelcome, and outmatched. Romero strikes him after another with one goddamn thing till implacability becomes the topic. That is his Powell film, and it’s touching to see him as a lifetime fan of Romero finally.

His thinking was simpatico, and Romero found himself in a position where the tiny budget he had. He wanted to see it all cheap and apparent since he tried to attract the attention of his audience to things that may appear customized but are right in front of us. An excellent example is a fun meal in this film. Two comical waiters with utensils are serving the wealthy guy who offends at dining near Maazel. Still, even if it has some sort of insanity from Chuck Jones, it is so blatant that he can only feel genuine by lifting the expensive dinner into his chair and bringing it to the other side of the table. Discrimination against the poor will not look like it here, but it will always feel like it. The latex masks, which indicate the evil images that haunt the park, have a more artless effect. Rob Zombie anticipates his wonderfully outraged America, a mentality that similarly avoided nuance in depicting the class struggle and male aggression because of the outrageous juxtaposition of Hell’s angels and 5-and-aft outfits.

Naturally, I do not believe that Zombie’s destiny for the young lovers was as distinctive as that of a fortune-teller. The wife notices that her husband is sick and cannot call her doctor because the apartment is wrecked, and the power or telephone is not present. She goes to her payphone to call the landlord, explaining how their run-down apartments are the tenants’ fault. The doctor responds to the telephone and hangs up just as soon, deciding not to assist the elderly wife or the strangely sick guy. She comes back to the flat and must stand, the eyes wobbling in agony. So, she walks down the street again to attempt to contact the doctor, but this time a procession drowns her cry out.

With the revealing of this missing film, the restoration of Orson Welles’ ‘The other side of the wind’ would be a worldwide child of artists like Romero. But to do this, the world should be far more interested in what horror films say. The world, in general, has never taken horror seriously since its emotions are regarded as trivial. We are being frightened or investigating what makes us so is not considered a significant effort. Romero maintained a reputation untainted by widespread approval because of the degenerate character of his research, even struggling for budgetary means at his old age. Roger Ebert stated, “There may be … a bit of a ghastly voyeur within us, in his review of “Dawn of the Dead.” We are afraid of it. We enjoy tremendous excitement. We claim we don’t want a film to go too far.” It is just. The only place ever headed was “Too far.” It is time we catch up with the rest of us.