As we all know by now, Disney has officially struck almost all non-movie Star Wars material from the official canon, a bold (but some might argue, well overdue) response to a franchise whose narrative tendrils have splayed in a ridiculous number of directions over the last couple of decades, with canonicity being somewhat-but-not-really managed by a Lucasfilm-crafted system that had become more like a five-headed beast of semantic shuffling.

Of course, this shouldn’t have come as any surprise to anyone who’s followed this franchise at all since the Prequels. Young Boba Fett should’ve been enough of a sign that the legitimacy of Extended Universe material was wholly revocable. Likewise, I don’t think anyone with half a shred of common sense really expected Kathleen Kennedy and J.J. Abrams to be okay with spending several years churning out adaptations of EU novels that have, for the most part, been resoundingly shit. Well okay, the Thrawn trilogy was pretty cool, and the X-Wing books. But still.

All in all, this means twenty years of Star Wars videogames have now been excised from the official lore. Like all the other EU media, they’re still around to be enjoyed and might possibly be rebranded under the Star Wars Legends banner (The new classification for material that essentially shifts non-endorsed material to ‘alternate universe’ status) but that seal of authenticity is now gone, which is understandably a bummer for those who still care about such things.

Either way, this marks the end of an era for Star Wars fans and especially those who enjoy the games. To mark this momentous occasion, we’re taking a look back at some of the highs and lows of original Star Wars stories in games, divided up into three distinct periods that for us signify the shifting eras of Star Wars fandom over the last couple of decades.

EPISODE ONE: THE GOLDEN YEARS (1993-1999)

While Star Wars games had been around since Kenner’s tabletop Star Wars Electronic Battle Command game in 1979, they had generally stuck to adapting the first three movies, or at least key sequences within them. The success of Timothy Zahn’s Thrawn trilogy, however, changed this. The novels proved that while Star Wars fans were now older their love of the trilogy was undiminished, and they were hungry for more. Lucasfilm were quick to capitalize with further novels, and LucasArts, still in the midst of their point-and-click hayday, were quickly brought onto the EU train.

1993

A mere two years after the release of Heir to the Empire saw the release of LucasArts’s first two completely original Star Wars games: one destined for notoriety, the other for classic status.

At the time, Rebel Assault was seen as a window to the future of games. Harnessing the incredible power of CD-ROM – LucasArts’s first release in the new format, in fact – the game turned heads with its FMV gameplay and full speech. Never mind that it controlled like a dead cow and looked like someone had made a flickbook of GameBoy Camera screenshots of the movies then threw up on it, in 1993 terms this was about as close to being in the movies as anyone could have imagined.

At the time, Rebel Assault was seen as a window to the future of games. Harnessing the incredible power of CD-ROM – LucasArts’s first release in the new format, in fact – the game turned heads with its FMV gameplay and full speech. Never mind that it controlled like a dead cow and looked like someone had made a flickbook of GameBoy Camera screenshots of the movies then threw up on it, in 1993 terms this was about as close to being in the movies as anyone could have imagined.

The game introduced a trope that was to become common in LucasArts’s Star Wars games of having the player character be someone participating in the events of the films, but removed enough so as not to have to be bound by the films’ plots. That said, Rebel Assault does let you ‘change the script’ in that it lets you take out the Death Star at the end of Episode IV instead of Luke. Apart from that, the game didn’t have a story as much as a grab-bag of scenes from the films around the periphery of which you could run/fly around shooting stuff.

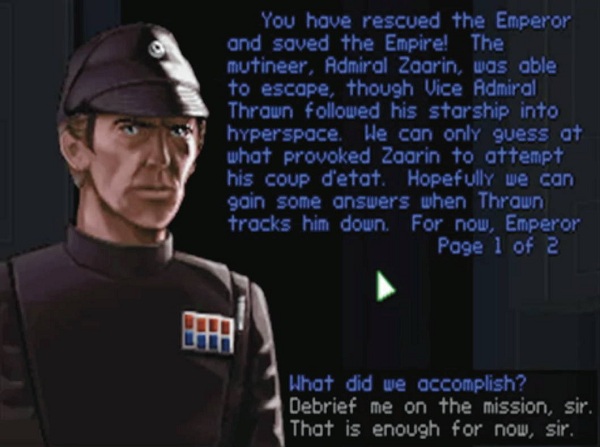

1993’s other big release, the great X-Wing, took this ‘background player’ idea and refined it. The game starts a few months prior to Episode IV, and casts you as a Rebel pilot engaging in a series of missions that culminate in the final assault on the Death Star. Apart from being, along with its sequel TIE Fighter, among the best Star Wars games ever made, it also saw LucasArts find the magic balance between adapting the movies yet giving the player a chance to discover their own stories among these events. Spread over three tours of duty, the missions begin with random sorties against Imperial forces but eventually involve the retrieval of the Death Star plans, the delivery of said plans to Princess Leia and eventually the Battle of Yavin (Where you play as Luke Skywalker, avoiding Rebel Assault‘s retconning).

1993’s other big release, the great X-Wing, took this ‘background player’ idea and refined it. The game starts a few months prior to Episode IV, and casts you as a Rebel pilot engaging in a series of missions that culminate in the final assault on the Death Star. Apart from being, along with its sequel TIE Fighter, among the best Star Wars games ever made, it also saw LucasArts find the magic balance between adapting the movies yet giving the player a chance to discover their own stories among these events. Spread over three tours of duty, the missions begin with random sorties against Imperial forces but eventually involve the retrieval of the Death Star plans, the delivery of said plans to Princess Leia and eventually the Battle of Yavin (Where you play as Luke Skywalker, avoiding Rebel Assault‘s retconning).

The magic of the game was the way it expanded on the militarized way the Rebel fleet was portrayed in Episode IV, and approaching the game very much like a ‘real’ fighter sim. This partly applied to the controls, possibly the best of any space sim ever, but also in the distinctly realistic feel of the missions themselves. Missions ranged to daring rescues and hit-and-run sorties to simpler recon and escort assignments more fitting of a pilot participating in a wider operation, and that sense of the practical and of playing a limited part in bigger events not only appealed to players’ memories of the movies but sold them on the universe at large. I’d wager that may of the older fans who saw their love of the trilogy rekindled in the 90s were in large part influenced by the way the X-Wing series brought a sense of groundedness and plausibility to the pure space opera of the films, and stands as a classic example not only of how you can create simple and effective storytelling at the periphery of a bigger story, but of how engaging the player on an emotional level can get you incredibly far by doing very little. The hook of the X-Wing series is the feeling that you’re actually in the universe, and LucasArts have never been smarter by giving you the tools and getting out of your way.

Well, within the game at least. X-Wing did have a central character and storyline; it was just up to you as to whether you wanted to read it. The ‘player character’ was technically Keyan Farlander, whose story is told in the Farlander Papers novella (included in early copies of the game) and continued in the game’s strategy guide. By keeping this material out of the game itself, however, LucasArts effectively gave the player the choice as to whether you wanted to recognize it or not. They basically let the player determine their own character, a philosophy that helps define some of this decade’s greatest games but would go into decline as the Star Wars games, and the franchise as a whole, would become increasingly obsessed with canonicity.

Well, within the game at least. X-Wing did have a central character and storyline; it was just up to you as to whether you wanted to read it. The ‘player character’ was technically Keyan Farlander, whose story is told in the Farlander Papers novella (included in early copies of the game) and continued in the game’s strategy guide. By keeping this material out of the game itself, however, LucasArts effectively gave the player the choice as to whether you wanted to recognize it or not. They basically let the player determine their own character, a philosophy that helps define some of this decade’s greatest games but would go into decline as the Star Wars games, and the franchise as a whole, would become increasingly obsessed with canonicity.

1994

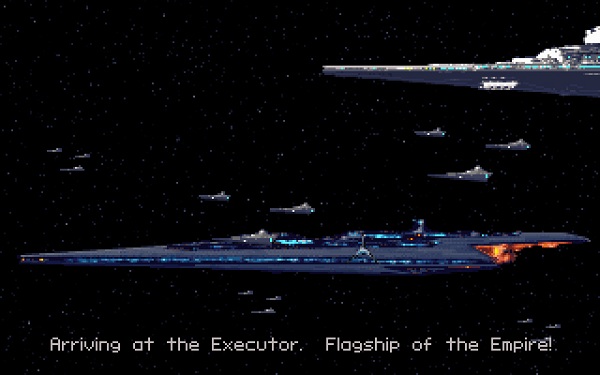

Sensing gold in them thar space sim hills, LucasArts were quick to follow up X-Wing with a sequel, TIE Fighter, the next year. The game improved on its predecessor across the board, including the story. Perhaps sensing that fans would engage with playing an Imperial slightly differently than with the Rebels, they introduced a more structured story that was wholly unlike anything Star Wars fans had yet experienced, in movie form or otherwise. Much of the story information is delivered in the form of Imperial propaganda that casts the Rebel Alliance as terrorists and traitors, no different from the pirates, defectors and various uppity alien races you put down in your career as a TIE pilot, itself a fun twist on the franchise. Knowing the weak pieces of shit those TIEs really were, it was certainly hard not to see those black-helmed TIE pilots blow up in the movies and not start to feel at least a little sorry for them.

Sensing gold in them thar space sim hills, LucasArts were quick to follow up X-Wing with a sequel, TIE Fighter, the next year. The game improved on its predecessor across the board, including the story. Perhaps sensing that fans would engage with playing an Imperial slightly differently than with the Rebels, they introduced a more structured story that was wholly unlike anything Star Wars fans had yet experienced, in movie form or otherwise. Much of the story information is delivered in the form of Imperial propaganda that casts the Rebel Alliance as terrorists and traitors, no different from the pirates, defectors and various uppity alien races you put down in your career as a TIE pilot, itself a fun twist on the franchise. Knowing the weak pieces of shit those TIEs really were, it was certainly hard not to see those black-helmed TIE pilots blow up in the movies and not start to feel at least a little sorry for them.

But role reversal was only part of TIE Fighter‘s narrative charm. It also added depth to the Empire, taking Vader’s schooling of that mouthy Imperial officer in Episode IV a step further with a Secret Order of the Emperor who enlists you to seek out disloyal elements in the higher ranks. This established the idea that the Empire was by nature divided, with the military and bureaucratic wing and the dark side element (which would eventually be grouped under the Sith) operating independently and not always harmoniously, an idea that would be alluded to further in future Star Wars games. Creatively it was an ingenious move, suggesting that there was more to the Empire as an institution than the faceless juggernaut portrayed in the movies and providing a loophole where by exposing/destroying the traitors the player could still ‘do the right thing’ – from a certain point of view.

1995

Although the first Rebel Assault was widely criticized for its restrictive (though some would prefer the term ‘non’) gameplay, it sold a boatload and encouraged LucasArts to come up with a sequel, Rebel Assault 2: The Hidden Empire. The hook this time was original FMV story sequences, the first live-action Star Wars material filmed since Return of the Jedi (That is, unless you count Caravan of Courage – but why would you do something silly like that?). Unfortunately, these efforts were somewhat wasted on a stock ‘find the secret weapon’ plotline that amounted to little more than an uninspired rehash of the first film. A disappointment, especially after X-Wing and TIE Fighter did so much to expand the lore of the franchise.

Although the first Rebel Assault was widely criticized for its restrictive (though some would prefer the term ‘non’) gameplay, it sold a boatload and encouraged LucasArts to come up with a sequel, Rebel Assault 2: The Hidden Empire. The hook this time was original FMV story sequences, the first live-action Star Wars material filmed since Return of the Jedi (That is, unless you count Caravan of Courage – but why would you do something silly like that?). Unfortunately, these efforts were somewhat wasted on a stock ‘find the secret weapon’ plotline that amounted to little more than an uninspired rehash of the first film. A disappointment, especially after X-Wing and TIE Fighter did so much to expand the lore of the franchise.

Thankfully Dark Forces, released the same year, did a much better job in all respects. Introducing fan favourite Kyle Katarn (in his pre-beardy lovechild-of -James-Remar-and-Vigo-the-Carpathian days) took a similar tack to the sim games and introduced espionage to the Star Wars franchise, wrapped in a superb FPS. Katarn is described as a mercenary though in this game he’s really more a blend of Han Solo and James Bond, dispatched by the Rebel Alliance in the first level to steal the Death Star plans (Apparently Death Star blueprints are the Star Wars equivalent of a hot potato: everyone holds them at some point).

Thankfully Dark Forces, released the same year, did a much better job in all respects. Introducing fan favourite Kyle Katarn (in his pre-beardy lovechild-of -James-Remar-and-Vigo-the-Carpathian days) took a similar tack to the sim games and introduced espionage to the Star Wars franchise, wrapped in a superb FPS. Katarn is described as a mercenary though in this game he’s really more a blend of Han Solo and James Bond, dispatched by the Rebel Alliance in the first level to steal the Death Star plans (Apparently Death Star blueprints are the Star Wars equivalent of a hot potato: everyone holds them at some point).

Much like the X-Wings, it wasn’t the actual plots that left an impression as opposed to the general tone, with Katarn’s down and dirty infiltrations feeling like a ground-based Special Ops alternative to X-Wing‘s military missions. Again, the story weaves in and out of the general saga, allowing the player to participate in it from a distance: another mission sees you rescue Imperial defector General Madine (Seen in Jedi), and elsewhere you encounter Jabba the Hutt and Boba Fett. The game also introduced the Dark Troopers, a kind of Stormtrooper-plus that while silly in concept would appear elsewhere in the EU and would prove popular enough to show up in later games.

The game’s main addition to Star Wars lore was, of course, Katarn himself. While he’s not an especially interesting character in and of himself, he happened to come along when fans were hungry for new heroes and as a result has achieved a long career in the EU. In Dark Forces he is introduced as an obvious Han Solo substitute, his status as an ex-Imperial mercenary blatantly mirroring Solo’s backstory. While rather dull in story terms, he provided players a Han Solo-esque experience without the ties to pre-established lore that would’ve been unavoidable if LucasArts has just gone ahead and made a straight Solo game. It wasn’t original but it worked, and would be a well LucasArts would return to in what would become known as the Jedi Knight series.

The game’s main addition to Star Wars lore was, of course, Katarn himself. While he’s not an especially interesting character in and of himself, he happened to come along when fans were hungry for new heroes and as a result has achieved a long career in the EU. In Dark Forces he is introduced as an obvious Han Solo substitute, his status as an ex-Imperial mercenary blatantly mirroring Solo’s backstory. While rather dull in story terms, he provided players a Han Solo-esque experience without the ties to pre-established lore that would’ve been unavoidable if LucasArts has just gone ahead and made a straight Solo game. It wasn’t original but it worked, and would be a well LucasArts would return to in what would become known as the Jedi Knight series.

1996

1996 was all about Shadows of the Empire, a multimedia extravaganza built around Steve (Not That One) Perry’s novel set between Empire and Jedi. Designed to build on the cultural impact of the Thrawn trilogy and, along with the Special Editions of the films to be released the following year, gauge the receptiveness of the public to new Star Wars movies, it was one of the first examples of the kind of multi-platform storytelling that has become par for the course these days. It was essentially as close to a new Star Wars movie as anyone had gotten in thirteen years, and arrived in a maelstrom of hype. Key to the story is its bridging elements between Empire and Jedi, namely the effort to rescue Han Solo from Boba Fett and a supercomputer holding the plans for the Second Death Star (Hot potato!). The story’s main antagonist, roofie-emanating crime boss Prince Xizor would also become something of an EU fan-favourite and pave the way for a slew of underworld-related spin-off material.

1996 was all about Shadows of the Empire, a multimedia extravaganza built around Steve (Not That One) Perry’s novel set between Empire and Jedi. Designed to build on the cultural impact of the Thrawn trilogy and, along with the Special Editions of the films to be released the following year, gauge the receptiveness of the public to new Star Wars movies, it was one of the first examples of the kind of multi-platform storytelling that has become par for the course these days. It was essentially as close to a new Star Wars movie as anyone had gotten in thirteen years, and arrived in a maelstrom of hype. Key to the story is its bridging elements between Empire and Jedi, namely the effort to rescue Han Solo from Boba Fett and a supercomputer holding the plans for the Second Death Star (Hot potato!). The story’s main antagonist, roofie-emanating crime boss Prince Xizor would also become something of an EU fan-favourite and pave the way for a slew of underworld-related spin-off material.

Adding to the anticipation for the game was the fact that it was one of the launch titles for the Nintendo 64. Unfortunately, its status as background material for a bigger story led to a rather uninspired set of levels that saw protagonist Dash Rendar skirt around the fringes of the book’s plot but have nothing that coalesced into a convincing story of his own. Neither was Dash the most charismatic of characters: having successfully created a Han Solo clone that players liked to play in Kyle Katarn, LucasArts struggled with giving Rendar much of note to do, as you might expect of a supporting character in a story simultaneously being told in different media. The Shadows of the Empire game is purely an exercise in narrative dot-joining, which is perfectly good fodder for a string of levels in an action game but hardly makes for compelling storytelling. Shadows may garner some affectionate looks back in terms of launch title nostalgia, but it was narratively one of the weaker elements of Lucasfilm’s multimedia campaign.

Adding to the anticipation for the game was the fact that it was one of the launch titles for the Nintendo 64. Unfortunately, its status as background material for a bigger story led to a rather uninspired set of levels that saw protagonist Dash Rendar skirt around the fringes of the book’s plot but have nothing that coalesced into a convincing story of his own. Neither was Dash the most charismatic of characters: having successfully created a Han Solo clone that players liked to play in Kyle Katarn, LucasArts struggled with giving Rendar much of note to do, as you might expect of a supporting character in a story simultaneously being told in different media. The Shadows of the Empire game is purely an exercise in narrative dot-joining, which is perfectly good fodder for a string of levels in an action game but hardly makes for compelling storytelling. Shadows may garner some affectionate looks back in terms of launch title nostalgia, but it was narratively one of the weaker elements of Lucasfilm’s multimedia campaign.

1997

1997 got off to a slightly disappointing start with the third of the X-Wing series, X-Wing vs TIE Fighter, taking a multiplayer focus and releasing with virtually no single-player or story content, alienating critics and fans. Given the prevalence of multiplayer over everything in many of today’s releases it seems that LucasArts were simply ahead of their time, and quickly added an expansion titled Balance of Power that added a couple of single-player campaigns which lacked the inventiveness of X-Wing and TIE Fighter‘s narratives. While the game would garner a following among online-friendly pilots, it was generally seen as a letdown and met with significantly less success than its forbears.

1997 got off to a slightly disappointing start with the third of the X-Wing series, X-Wing vs TIE Fighter, taking a multiplayer focus and releasing with virtually no single-player or story content, alienating critics and fans. Given the prevalence of multiplayer over everything in many of today’s releases it seems that LucasArts were simply ahead of their time, and quickly added an expansion titled Balance of Power that added a couple of single-player campaigns which lacked the inventiveness of X-Wing and TIE Fighter‘s narratives. While the game would garner a following among online-friendly pilots, it was generally seen as a letdown and met with significantly less success than its forbears.

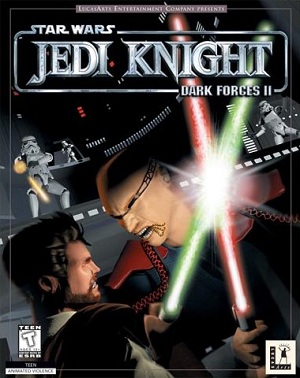

The real star of the year was Star Wars: Jedi Knight: Dark Forces II, which introduced two key aspects that would define the series from here: convoluted titling schemes, and lightsabers. Having teased Kyle Katarn’s Force-friendliness at the end of Dark Forces, LucasArts shifted him a little further in the direction of Luke Skywalker and created the first successful attempt at putting Jedi powers into a game. The game also saw a morality system employed in a Star Wars game, with the player’s actions and choices of powers able to push Katarn towards the light and dark sides of the Force. This mechanic was hugely popular, and would be expanded in games such as 2003’s Knights of the Old Republic and its sequel.

The game’s plot was equally strong, despite the horrendous FMV sequences:

Smartly, the game takes its time giving Katarn his lightsaber, instead starting him off in Han Solo mercenary mode and making him discover his past and connection with the Force gradually. This gave fans of the first game a decent shooting fix while building anticipation for the Jedi action to come, and while Jerec is a pretty goofy antagonist (having apparently graduated from the General Katana school of mugging) his minions make for a fun cast of enemies to pursue. Katarn’s search for the Valley of the Jedi is highly enjoyable, doubly so for it the time in which the game was released. People often forget that at the time of Jedi Knight‘s release The Phantom Menace had barely finished shooting, and fans were ravenous to learn more about the heroic order that had been a source of mystery for a decade and a half. Jedi Knight gave us the first serious hints at the Jedi’s history, and gave Katarn a depth that was absent in the first game. Even today Jedi Knight is a hugely enjoyable romp that is a great reminder of the mystique the Jedi had before the Prequels came and deflated it.

What’s also interesting is how Jedi Knight adopts the common early-EU trope of active Force users who are not affiliated with the Jedi or Sith. The Prequels soon brought into canon a rather two-tone interpretation of life as a Force-sensitive, i.e. that you were either a Jedi or a Sith and that was pretty much that. Back in the Nineties, however, the lines were far less defined: Luke Skywalker doesn’t actually become a Jedi until the end of ROTJ, and even then it’s in name only, and ‘Sith’ only existed as a mysterious term included in Darth Vader’s title. It’s only with the Prequels that the two orders became the only choices, and even Jedi Knight‘s expansion Mysteries of the Sith (Released the following year) doesn’t make too many specifications.

What’s also interesting is how Jedi Knight adopts the common early-EU trope of active Force users who are not affiliated with the Jedi or Sith. The Prequels soon brought into canon a rather two-tone interpretation of life as a Force-sensitive, i.e. that you were either a Jedi or a Sith and that was pretty much that. Back in the Nineties, however, the lines were far less defined: Luke Skywalker doesn’t actually become a Jedi until the end of ROTJ, and even then it’s in name only, and ‘Sith’ only existed as a mysterious term included in Darth Vader’s title. It’s only with the Prequels that the two orders became the only choices, and even Jedi Knight‘s expansion Mysteries of the Sith (Released the following year) doesn’t make too many specifications.

The shame is, this idea of ‘Jedi’ and ‘Sith’ being options in the uncharted waters of Force sensitivity makes for a much more compelling idea of the Force than the binary paths set by the Prequels. This narrowing of scope helped to strip the Force of a lot of its coolness in the pre-prequel era, and if anything could be salvaged for the new movies and the unified canon it’d be nice if this idea of non-affiliated Force use could be rescued.

Remember, I said nice. Not likely, but nice.

1998

The only release in this year to attempt any significant kind of story was Rogue Squadron, which released on N64 and PC to great acclaim. An arcadier take on the flight action of the X-Wing series, the game boasted hugely impressive graphics and succeeded in delivering an experience that arguably surpassed the Rebel Assaults and Shadows of the Empire in bringing the cinematic Wars experience to games.

But while Rogue Squadron was fun, it was as much a step down in story from the X-Wings than it was in complexity. While taking some cues from the sims in terms of mission structure, with escort and rescue missions featuring heavily, the game lacked the dash of realism that made those games so absorbing on a personal level. This was exacerbated by some odd narrative choices, such as rescuing Crix Madine in an apparent retcon of Dark Forces. That’s not to say that the story doesn’t have its charms, however: the formation of Rogue Squadron is fun to see play out, and you can never have enough Wedge. But at the end of the day the plot is hardly memorable either, its loosely connected grab-bag of missions lacking that sense of cohesion and atmosphere that the X-Wing series’ sim structure provided. As an arcadey romp starring the Rebel Alliance’s coolest flyboys, however, Rogue Squadron did a fine job.

But while Rogue Squadron was fun, it was as much a step down in story from the X-Wings than it was in complexity. While taking some cues from the sims in terms of mission structure, with escort and rescue missions featuring heavily, the game lacked the dash of realism that made those games so absorbing on a personal level. This was exacerbated by some odd narrative choices, such as rescuing Crix Madine in an apparent retcon of Dark Forces. That’s not to say that the story doesn’t have its charms, however: the formation of Rogue Squadron is fun to see play out, and you can never have enough Wedge. But at the end of the day the plot is hardly memorable either, its loosely connected grab-bag of missions lacking that sense of cohesion and atmosphere that the X-Wing series’ sim structure provided. As an arcadey romp starring the Rebel Alliance’s coolest flyboys, however, Rogue Squadron did a fine job.

1999

February of this year saw the release of X-Wing Alliance, the fourth and so far last of the X-Wing/TIE Fighter series. Taking on board criticisms of the lack of campaign material in X-Wing Vs TIE Fighter, LucasArts doubled down on story in this installment by putting the player in the shoes of the series’ most thoroughly defined character yet: Ace Azzameen, the youngest member of a neutral family of traders. In fact, you begin the game not taking part in the war at all and doing training missions with the family, removed from the wider conflict.

However, when the family are victimized by the Empire Ace falls in with the Alliance and you take part in various events from the movies and EU such as the evacuation of Hoth and the retrieval of the Death Star II plans from the freighter Suprosa (from Shadows of the Empire). The story sees you alternating missions for the rebels with helping your family defend themselves against a rival trade corporation, culminating in the Battle of Endor in which you take Lando’s seat and fly the Millennium Falcon.

However, when the family are victimized by the Empire Ace falls in with the Alliance and you take part in various events from the movies and EU such as the evacuation of Hoth and the retrieval of the Death Star II plans from the freighter Suprosa (from Shadows of the Empire). The story sees you alternating missions for the rebels with helping your family defend themselves against a rival trade corporation, culminating in the Battle of Endor in which you take Lando’s seat and fly the Millennium Falcon.

While Alliance is arguably the most reliant of any of the X-Wing series on pre-existing story events, Ace’s family story provides effective counterpoint and stays true to the series’ tradition of showing what the rank and file of the Star Wars universe get up to while the classic characters are off having their adventures.

Unfortunately, X-Wing Alliance would prove to be not just the final hurrah of LucasArts’ space sims, but of an entire era of Star Wars games. Three months after Alliance‘s release The Phantom Menace hit the big screen, and with it would come a significant change in the nature of LucasArts’s work…

TO BE CONTINUED IN EPISODE TWO: THE PREQUEL YEARS