Film Literacy

In which Bart attempts to expand his film knowledge, both the history and the methodology, by sticking his nose in a few good books. Having no background in film outside of an intense love and amateur curiosity, nevertheless his goal is to find something, anything, to recommend to you, the constant reader. Suggestions are certainly welcome, with the understanding that this column will be a once-a-month thing, allowing Bart to read and then, loving, review each book.

Previously: Blockbuster.

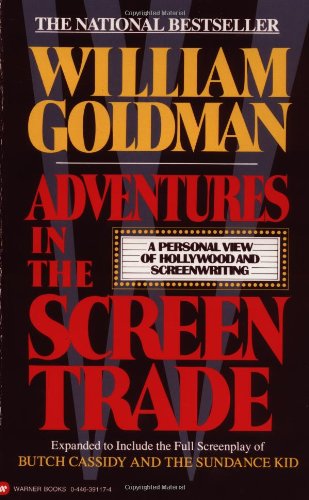

William Goldman has had a long and varied career as a Hollywood screenwriter. His works range from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid to All the President’s Men to The Princess Bride, but he is also known for his books, both fiction and non-fiction. His most well-known work of non-fiction is, by far, Adventures in the Screen Trade, his part memoir of his Hollywood experiences, part advice on and demonstration of the screenwriting process from ink to screen. Written in 1982 at the height of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial fever and published in 1983, 30 years on it offers up an insightful view from a Hollywood outsider that didn’t like the direction the industry was going. In the wake of Spielberg and Lucas, Goldman was at ground zero of the blockbuster’s toddler years and yet still trying to bring a little bit of class to his work. At the heart of this is the repeated adage, “Nobody knows anything,” about what movies hit big, but more importantly is the accompanying “Screenplays are structure”, which modern screenwriters should have to write on a chalkboard 100 times in a row before starting work on a movie.

The 1983 edition of the book (there was a 2nd edition released in 1996) is broken up into three parts: “Hollywood Realities”, “Adventures”, and “Da Vinci”. The first section lays the groundwork and attempts to teach the reader the language of Hollywood, offering up a bit of history and abstractly defining the jouissance of that dream-like place. The second section borders on gossip rag at times, offering up behind-the-scenes stories and the inside scoop on celebrities but, more importantly, is done so in memoir format with Goldman chronicling his rise from aspiring novelist to being on set with Laurence Olivier. The third section is a bit undercooked, unfortunately, as Goldman rushes through how adapting one of his short stories to the screen would work by including the prose story, a pre-writing thought process, a screenplay version, and then interviews with a designer, cinematographer, editor, composer, and director.

What’s significant and extremely accessible about Goldman the writer, as opposed to Goldman the person, is the tone and attitude of this jeremiad. As evident from his works, especially those that have made it to the screen with his clear stamp, he has a bit of an irreverent streak. Being a Midwestern kid, he’s horrified by the whole culture of Hollywood, allowing him a bit of dissonance from that world. In terms of his role there he’s very blunt, describing screenwriters as ranking “somewhere between the man who guards the studio gate and the man who runs the studio (this week)” (xii). What’s commendable, moreover, is his love not just of cinema but of the cinema experience. He begins the first section with an anecdote about what going to the movie theater meant for him as a child. It’s obvious that he believes in the powerful communal effect of going to see a movie, something that’s being lost in the 21st century. It’s obvious, as well, that he believes cinema is a form of art (although he never uses that phrasing), and was becoming increasingly frustrated with the Hollywood factory system and what he deemed the “comic-book movie”.

This is laid out in the second section and, unfortunately, this is where Goldman the person butts heads with Goldman the writer. As a writer, his style is comparable to John Irving in its slightly subversive portrayal of an America on the verge of violence, with a penchant for both strictly researched realism and magical realism, a fine line to walk. What bridges that gap is his hard-line emphasis on the unifying theme and heart of a story. Repeatedly in his adventures he wrote screenplays based on real-life events (Butch Cassidy, All the President’s Men, The Right Stuff), and repeatedly he shows a great understanding of finding the story within those series of events and that’s in the character. This is brushed off as a shortcoming, his inability to be flexible as a writer, but there’s also an implicit and somewhat elitist message there about what he values in a story. He spends an entire chapter, titled “The Ecology of Hollywood”, lamenting the dominance and influence of Spielberg and Lucas and their “comic-book movies”, which he calls “empty calories” while being quick to say that’s not in the “pejorative connotation” of “junk food” (152).

The knee-jerk reaction would be to assume that he’s talking about what is known today as the “pop corn movie” or the blockbuster. Especially in light of Tom Shone’s exploration in Blockbuster, one might find bewilderment at Goldman’s bewilderment. In 1982, he was at the epicenter of intelligent, engaging action-adventure spectacles like Raiders of the Lost Ark, but he wasn’t lamenting a dip in quality but rather an evolution in the storytelling method. He doesn’t, in fact, single out the blockbuster, putting the Academy Award winning The Deer Hunter in his sights with his real grievance being narrative shorthand, or more likely what he views as contrivance. Goldman is all about emotional honesty, but not at the expense of the screenplay’s structure, so rules must be established and then cannot be broken. The Deer Hunter, for instance, suffers in Goldman’s eyes because of Robert De Niro’s ability to slip into Saigon during wartime, and Christopher Walken’s ability to win at Russian roulette for months against all odds. This is where he and I disagree, because, the majority of the time the whole impetus of a cinematic narrative is the rarity of the circumstances.

Take, for instance, his virtual adaptation in the third section of his short story “Da Vinci”. It really only works in the broad, allegorical sense in that it’s framed around a theme. It lacks emotional honesty in how the relationships between Willie and Porky and Willie and his father play out, and the narrative is anchored upon convenience and brevity. “Comic-book movies”, by his definition, suffer from truncated and bifurcated plots in order to entertain, but I would argue in the case of Raiders of the Lost Ark and The Deer Hunterthat simplification ties together both theme and emotional honesty, putting the characters front and center at the expense of logic. Character, after all, is the first step to drama. He has a similar problem with horror films, which is understandable considering the Slasher genre was it its nadir in 1982, but those films are generally all allegory with paper-thin characters. The best of them, like Halloween, inject fascinating social commentary and mythic meaning into that allegory, something Goldman would dismiss as “You don’t fret a whole lot about subtext if you’re writing Halloween VI or Conan the Barbarian” (127).

This third section is commendable at least because it’s advocating original work and having a real purpose when working in film. In this case, “Da Vinci” is meant to convey that art and taking one’s time is no longer appreciated in the modern world. This, again, is an overriding theme in much of his work, as there’s a sense that some innocence has been lost, an era is over and the world has moved on. Only with The Right Stuff did he go on with the stringent message that America is still a good place to live. With “Da Vinci”, the commentary from the industry experts is truly enlightening, although Goldman is quick to note that this kind of back and forth would never be possible in Hollywood, giving the theme of “Da Vinci” a meta-commentary on the entire endeavor. The best part is after the polite attempts at conceptualizing “Da Vinci” in film form by the designer, editor, cinematographer and so forth, director George Roy Hill (Butch Cassidy, Slaughterhouse-Five, The Sting) comes in and tears Goldman apart, declaring that Goldman’s screenplay is “a physical drain” as it attempts to convey unknowable beauty in moments like a haircut, something Hill concludes is impossible (393).

Don’t go in expecting a how-to guide on screenwriting. Instead, Adventures in the Screen Trade is a necessary read for those that want to break into Hollywood and a fun read for those intrigued by it. It’s certainly not unbiased, as every word is Goldman’s blunt opinion, but it’s all earned and worth your time. I don’t always agree with what he has to say, but I respect it and was always entertained.