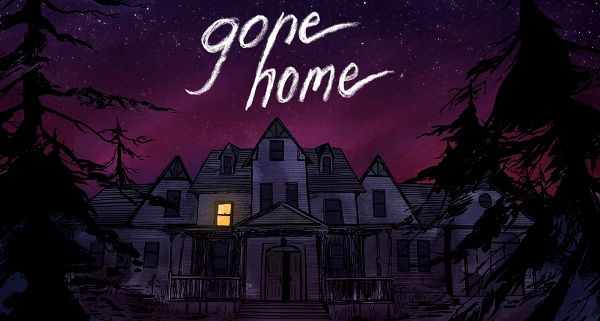

As you probably already gathered from our review, we liked Gone Home a whole lot. The Fullbright Company’s audacious debut has caused quite a stir in the gaming community, serving up a genuinely enjoyable exercise in atmosphere and exploration (Apt for a crew who have been closely involved with the Bioshock franchise), while sparking debates we’re not used to having as gamers.

We spoke to creative lead Steve Gaynor and co-writer/2D artist Karla Zimonja about Gone Home and its reaction, and about the cultural expectations of gaming and how they are steadily evolving.

Steve and Karla were very generous with their time and gave a lot of fascinating insights into the experience of running a small indie studio, as well as the resources available when refining and promoting low-budget games. It’s rare to see a company approaching the development process in such an intimate and low-key way, sharing the house that doubles as their studio and home. It sounds like a sitcom pitch in the making, but Gone Home shows that it may be a quite ingenious way of making games of a character we rarely associate with the medium.

Steve and Karla were very generous with their time and gave a lot of fascinating insights into the experience of running a small indie studio, as well as the resources available when refining and promoting low-budget games. It’s rare to see a company approaching the development process in such an intimate and low-key way, sharing the house that doubles as their studio and home. It sounds like a sitcom pitch in the making, but Gone Home shows that it may be a quite ingenious way of making games of a character we rarely associate with the medium.

SPOILER WARNING: Gone Home is best enjoyed knowing as little about the story or premise as possible. Our conversation necessarily wandered into Spoiler Territory, and while we’ve made an effort to say as little as possible overtly, some important story points had to be openly addressed in order to discuss them fully. We strongly recommend that if you are intending to play the game, you do so before reading this interview.

Cav: How did The Fullbright Company come about, and how does it compare to your experiences in large companies?

Steve: For me a lot of it was a question of contrasts, because we had worked together on Bioshock 2 which was a large team, and then the Minerva’s Den DLC which is a much smaller team within a big organization. We all had this investment in that project and felt a lot of ownership of it, a thing we had made together. And then I went off and joined an even bigger team on an even bigger project (Bioshock Infinite). A year there made me realize that I really wanted to work on stuff that was smaller and with people I’d worked with before, and that was when I contacted Karla and Johnnemann [Nordhagen, Programmer] and we started talking about Fullbright. There are a lot of different challenges, because in a big company it’s always somebody’s job to get all the little bits and pieces done. There are producers, people that handle licensing and legal stuff. When you’re a team of four people, if there’s something that needs to get done, one of the four of you is going to be doing it! You can’t say there’s someone else that handles that thing I don’t know how to do, so you have to learn how to deal with stuff like music licensing, writing press releases and all that, which has been really interesting.

Steve: For me a lot of it was a question of contrasts, because we had worked together on Bioshock 2 which was a large team, and then the Minerva’s Den DLC which is a much smaller team within a big organization. We all had this investment in that project and felt a lot of ownership of it, a thing we had made together. And then I went off and joined an even bigger team on an even bigger project (Bioshock Infinite). A year there made me realize that I really wanted to work on stuff that was smaller and with people I’d worked with before, and that was when I contacted Karla and Johnnemann [Nordhagen, Programmer] and we started talking about Fullbright. There are a lot of different challenges, because in a big company it’s always somebody’s job to get all the little bits and pieces done. There are producers, people that handle licensing and legal stuff. When you’re a team of four people, if there’s something that needs to get done, one of the four of you is going to be doing it! You can’t say there’s someone else that handles that thing I don’t know how to do, so you have to learn how to deal with stuff like music licensing, writing press releases and all that, which has been really interesting.

Cav: How did you approach the environment-driven narrative?

Steve: It’s a little bit of a chicken and egg thing. We’re a small studio but we also wanted to do stuff we had experience with and we felt that we were good at. And so when we were talking about what we wanted to make, it came down to that we’d made these games that were about exploration and non linear traversal through a first person space, with atmosphere and discovering stuff. So for us it was more achievable to say, ‘Let’s just make an environment and distribute the story throughout it, and we’ll make the game the finding of that story’. And we were more interested in trying something that didn’t have more traditional ‘gamey’ elements; we’ve all shipped stuff that has those kinds of elements in it, and playing those games is fun, but on the other hand taking that stuff out just allowed us to do things that we couldn’t have done at all if it had been a more traditional game.

Cav: It’s rare to see a game that completely takes place in the real world without any conceptual ‘heightening’. When it comes to designing a game like that, does that require a different approach from a more traditional kind of game world?

Karla: It doesn’t really make that much of a difference. A lot of that was handled by Kate (Craig, 3D Environment Artist). Either way you have something to refer to, which in our case was the Sears catalogue – which is a little different from what the concept art pile usually is. But you refer to something and you try to make it adhere to that as best you can. Whether it’s fantastical or someone’s awful wicker thing – which is also fantastical when you think about it – it’s really the same process.

Karla: It doesn’t really make that much of a difference. A lot of that was handled by Kate (Craig, 3D Environment Artist). Either way you have something to refer to, which in our case was the Sears catalogue – which is a little different from what the concept art pile usually is. But you refer to something and you try to make it adhere to that as best you can. Whether it’s fantastical or someone’s awful wicker thing – which is also fantastical when you think about it – it’s really the same process.

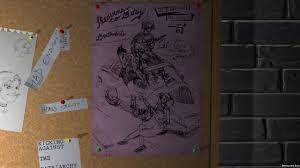

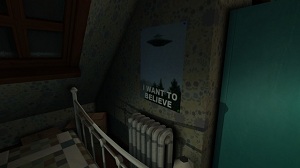

Steve: I think something that’s interesting though, is that Karla’s contribution to the game was very similar to the stuff she did on Minerva’s Den regardless of the setting being different. She made the posters in Rapture and all these cool reproductions of these old passports, and-

Karla: Don’t forget the telegrams, Steve! (Laughs)

Steve: Oh yeah! So I assume that was a close parallel between the two projects.

Karla: Yeah, they’re both really similar. It’s just trying to keep close to your reference material and making it believable.

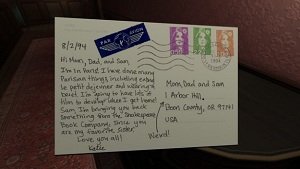

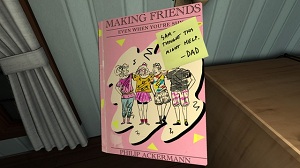

Cav: It’s not every day you find yourself admiring handwriting in a game. Karla, as the 2D artist how different would you think your job would have been if Gone Home was set today?

Karla: It would be pretty different! Think today of something you could strew around your house that people could find and read about you. It would be… A phone, and that’s it. Maybe a laptop somewhere else. Nothing is distributed anymore, nobody keeps boxes of old emails in the back of their closet. I hope! (Laughs)

Karla: It would be pretty different! Think today of something you could strew around your house that people could find and read about you. It would be… A phone, and that’s it. Maybe a laptop somewhere else. Nothing is distributed anymore, nobody keeps boxes of old emails in the back of their closet. I hope! (Laughs)

Steve: Maybe my Mom does, she tends to print out a lot of details for some reason!

Karla: That is true, I think mine does too… Okay, so maybe moms! Maybe we could do a Mom story.

Steve: That is a big reason we set it fifteen years ago. So much was physical and conveyed in notes and letters and Post-It notes stuck to things. Mechanically, starting from the very first point of what you do in this game we wanted you to explore the environment and find bits and pieces of the story that you reconstruct. If it’s ‘Oh, I left you my iPhone’ You’re done! (Laughs) It’s a very different game. I’m not saying you couldn’t make an interesting story exploration game that’s set in 2013. It just wouldn’t have been the one that we made.

Cav: The game is very carefully structured around this as well. It guides the player along but always keeps exploration to the forefront, which means putting a lot of trust the player to find the relevant story information. How did you balance these things?

Cav: The game is very carefully structured around this as well. It guides the player along but always keeps exploration to the forefront, which means putting a lot of trust the player to find the relevant story information. How did you balance these things?

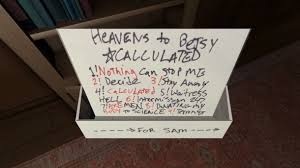

Steve: A lot of that technique came from working on the Bioshock series, and that in itself was an extension of the System Shock series and Deus Ex, where there’s all this distributed narrative you can find in the environment. A lot of it is just prioritizing, like hierarchical placement of objects. The stuff that has Sam’s audio diaries attached to them, for example, is like the spine of the story, what everything else hangs around. So as a level designer you try and make sure you put the important stuff in a place that’ll be hard to miss. Then you go from there and say “Well, if something is more of a supporting concept or just fleshes out this one character a little bit but if you don’t see this thing you won’t lose the thread of what’s going on, you can hide that under a hidden panel or inside a draw and maybe nobody will ever find that, but since our game is about exploration and investigating this space the converse is that if someone does look hard enough and does find it, and knows ‘Oh, not everybody found this, they feel more invested and more rewarded by finding it, and put additional significance on it.

Karla: Yeah, and people are naturally curious, and we believe that that being a basic human drive would get people through the game. A thing that is really easy to be curious about is other people, and so it all falls together in a nice way, I think, just in the sense of you find a little bit and it’s not too find more, and that builds on itself and you get more and more interested.

Steve: It’s partially thinking where might this stuff actually go in real life, and it’s partially a video game level design/player path kind of thing. One thing that’s interesting about players’ approaches to the game, is that we playtested the game at the Game Developers Conference. Obviously a lot of people there work in the game industry, but a lot of them aren’t game designers but marketers or whatever. So in various contexts we had people come up and play the game and we would see that if someone was a very gamer-focused person who played a lot of games, they would go into the foyer at the beginning, would see the big set of stairs in front of them, and then they would start looking round and dig through the whole foyer and find everything. People almost always ended up going into the west hall first, which is how the intended progression goes. But someone who was less familiar with gaming tropes and didn’t have this ingrained instinct of ‘Okay, I’m in this space so I should to find everything in it first before I move on’ and without that gamer baggage, would be more likely to just go ‘Oh, stairs. There’s a door up there’ and just go upstairs (Laughs). And we support that way of doing it, I mean they eventually have to come back downstairs to get the next part of the story, but It’s been interesting to see how people’s experience and playing styles have influenced how they play Gone Home.

Steve: It’s partially thinking where might this stuff actually go in real life, and it’s partially a video game level design/player path kind of thing. One thing that’s interesting about players’ approaches to the game, is that we playtested the game at the Game Developers Conference. Obviously a lot of people there work in the game industry, but a lot of them aren’t game designers but marketers or whatever. So in various contexts we had people come up and play the game and we would see that if someone was a very gamer-focused person who played a lot of games, they would go into the foyer at the beginning, would see the big set of stairs in front of them, and then they would start looking round and dig through the whole foyer and find everything. People almost always ended up going into the west hall first, which is how the intended progression goes. But someone who was less familiar with gaming tropes and didn’t have this ingrained instinct of ‘Okay, I’m in this space so I should to find everything in it first before I move on’ and without that gamer baggage, would be more likely to just go ‘Oh, stairs. There’s a door up there’ and just go upstairs (Laughs). And we support that way of doing it, I mean they eventually have to come back downstairs to get the next part of the story, but It’s been interesting to see how people’s experience and playing styles have influenced how they play Gone Home.

Cav: Reactions seem to vary a lot based on individual peoples’ ‘game literacy’.

Cav: Reactions seem to vary a lot based on individual peoples’ ‘game literacy’.

Steve: Yeah, and we didn’t want to design the game so such a way that it’s like, you’re not going to get anything out of this unless you know all the game conventions, but it’s interesting to think that maybe if you don’t have that familiarity it’s additionally interesting. You come in without kind of thinking you don’t have any idea how this is going to go, but on the other side of that, there’s been a lot of good writing that we’ve read about people who talk about how a big part of their enjoyment of the game was seeing the tropes we start off pointing at and the imagery and the implications of the kind of game it is, and the surprise and enjoyment of seeing those things being subverted by not going the way that they normally do in games.

Karla: Yeah, we definitely wanted to be very accessible so that’s cool to hear if people who’re less used to games might like it.

I found myself expecting things to end up in a more traditionally ‘videogamey’ fashion, but consciously hoping that it wouldn’t.

Karla: I’ve heard from a couple of people who have gone into it, and they’re all ‘I knew what was going to happen and there was going to be death and murder and horrible things, and then by the end I was praying that wouldn’t be the case’! (Laughs) That’s a really good thing.

Cav: A lot of that is due to the characters. Were they written from a thematic basis first and the game built around that, or did they evolve as the game shaped itself?

Cav: A lot of that is due to the characters. Were they written from a thematic basis first and the game built around that, or did they evolve as the game shaped itself?

Steve: It definitely came from the needs of the game first. Something that is really important to us is that you always start from what is the game, what are the mechanics and what does the player do and why is that interesting, and then that forms the constraints for everything else. So for us it was definitely a case of ‘You’re exploring this empty house, there’s a family who’re supposed to be here so why aren’t they here?’ The big question that starts the game and story that we had to answer. So to have conflict in this family we drew on the idea that if the kid falls in love with someone the family doesn’t approve of, that causes conflict and could lead to the drama of the story. We decided who the core players of this conflict were in an archetypal way, but then thought about who they are as individuals, and it continued from there. Something that’s interesting about what you said about not wanting the game to end in certain ways because of the characters – it was kind of the same for me when writing the story. I started from a certain point of ‘Okay, this will end in like a melancholy way, and the girls will want to be together and they won’t be able to and it’ll be sad and wistful’… And then I was just like, ‘Fuck this! I like these characters too much to be mean to them’. It still needs to be an interesting, conflicted, unpredictable story; I mean, you still have to worry that it might end badly, but late in the development we had to do a lot of work to figure out how can the drama be about them being pulled apart but the resolution be about getting them to be together? But then again, after the credits roll they’re still in a pretty dicey situation. But at least in the moment, they’ve decided to try which is more interesting to me than ‘This can’t work’.

Cav: The game is most effective the less the player knows, though you have to tell people about the game to promote it – and Gone Home generated a sizable amount of online buzz even during development. How did you manage the information going out there?

Cav: The game is most effective the less the player knows, though you have to tell people about the game to promote it – and Gone Home generated a sizable amount of online buzz even during development. How did you manage the information going out there?

Steve: It’s been kind of interesting because we haven’t had to do that much, honestly! Starting last March we started building the game and the deadline for the Independent Games Festival was in October, so we said ‘Okay, we have six months to make the first part of this game at a highly polished level then submit it for the IGF’. So that was the first hour of the game, which we gave to hundreds of IGF judges and we had the press preview it, and I figured that anything in that was fair game, as that was the premise of the story. But totally voluntarily, no journalists talked about the deeper overarching themes of the story and of Sam and Lonnie’s relationship, because some of them said to us, ‘Discovering that part of the story was really powerful for me and I wouldn’t want to spoil that for anybody who reads about it’, and when we sent out review code I asked people to avoid anything that was an obvious spoiler but trust your judgement. I think because people found the experience of playing through the game powerful, just from their own volition they told people as little about the specifics as they could.

Karla: Even though it seems like Sam and Lonnie’s relationship is sort of a given in the story, it doesn’t really form until a little further into the first part of the game, and we’ve had people say that they were genuinely on tenterhooks, going ‘My God, can it be? Is it true?’. And I would hate to take that away from someone if that means the most to them.

Karla: Even though it seems like Sam and Lonnie’s relationship is sort of a given in the story, it doesn’t really form until a little further into the first part of the game, and we’ve had people say that they were genuinely on tenterhooks, going ‘My God, can it be? Is it true?’. And I would hate to take that away from someone if that means the most to them.

Cav: Nothing’s worse than a review that makes actually playing the game redundant.

Karla: I know… (Laughs)

Cav: There’s been a bit of controversy regarding the length of the game versus the price. Do you think games like Gone Home require different parameters when it comes to setting a price to it?

Steve: Everybody has their own threshold for what they feel is an acceptable value proposition. But, you know, there’s going to be Steam sales so I hope that people who feel that the initial price tag is too high will jump at the chance when the game is half off or whatever. We very intentionally priced the game to what we hoped the quality level was, and to what the value and detail and what you get out of the experience, as opposed to ‘Well here’s 20 hours!’ But yeah, if some people are not up for it there’ll be plenty chances to get it later.

Cav: The game’s one of many that have pushed a lot of buttons regarding traditional perspectives of what a game is/should be.

Steve: I think for us, if anything, I’m grateful that there is any kind of controversy because it means that people give a shit! (Laughs) It could’ve just sunk like a stone and it would’ve been a ‘thing’, and there would’ve been nothing.

Karla: A very Oscar Wilde viewpoint. Good job! (Laughs)

Steve: Well, I definitely don’t subscribe to the point of view of ‘If you made people feel anything at all then you’ve succeeded’. It’s really easy to push people’s buttons and get them riled up in a totally artificial way, but that said just the fact that people are talking about this is better than if they weren’t. It’s a case of slowly changing perspectives, but they only change when there’s something that upsets the status quo. We’re just part of this zeitgeist of games that are doing this: Dear Esther, Proteus and Antichamber and The Witness by Jon Blow, even Portal… Games that are about being in a space in first person but it being about a shorter and more contained experience about something other than defeating enemies, all the way to the biggest extreme of that which is 30 Flights of Loving which is like only fifteen minutes long, and I think really inspiring and experimental and cool. If we’re one of the more prominent examples of that exploration into a new space in what gamers think of games being, I think that’s really exciting and I’m comfortable with some people being uncomfortable with that.

Steve: Well, I definitely don’t subscribe to the point of view of ‘If you made people feel anything at all then you’ve succeeded’. It’s really easy to push people’s buttons and get them riled up in a totally artificial way, but that said just the fact that people are talking about this is better than if they weren’t. It’s a case of slowly changing perspectives, but they only change when there’s something that upsets the status quo. We’re just part of this zeitgeist of games that are doing this: Dear Esther, Proteus and Antichamber and The Witness by Jon Blow, even Portal… Games that are about being in a space in first person but it being about a shorter and more contained experience about something other than defeating enemies, all the way to the biggest extreme of that which is 30 Flights of Loving which is like only fifteen minutes long, and I think really inspiring and experimental and cool. If we’re one of the more prominent examples of that exploration into a new space in what gamers think of games being, I think that’s really exciting and I’m comfortable with some people being uncomfortable with that.

Karla: It is really good to have the chance to put characters like Sam and Lonnie in the spotlight of a game, just to give people another reference point since there really aren’t that many. It feels really nice to contribute culturally in that way, just to give games a little bit of visibility and something to identify with. That really feels like an important thing to me and I’m glad we got to do it, and I hope it’s even just a tiny bit meaningful to someone somewhere.

Karla: It is really good to have the chance to put characters like Sam and Lonnie in the spotlight of a game, just to give people another reference point since there really aren’t that many. It feels really nice to contribute culturally in that way, just to give games a little bit of visibility and something to identify with. That really feels like an important thing to me and I’m glad we got to do it, and I hope it’s even just a tiny bit meaningful to someone somewhere.

Steve: Yeah, it’s been really cool to see reviewers or bloggers or even someone who’s emailed us just to say, ‘I saw myself in these characters in a way I’ve never seen in a game before’, and if we can give people who feel like they aren’t represented in this medium that they love someone to see themselves in, I’m really proud of that.