There remain a few scattered theatrical runs for Shane Carruth’s Upstream Color, but this last week the film has joined Netflix’s Instant Watch roster, which is likely to put it in front of more eyeballs than ever. It’s the kind of film one might be prone to queue and wait for that right moment to watch, only to find yourself still saying, “I should sit down and watch that,” a year later.

Allow me to encourage you to avoid that scenario and see the film as soon as possible.

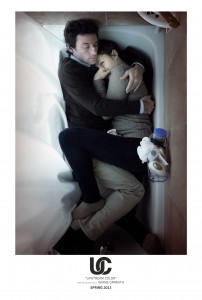

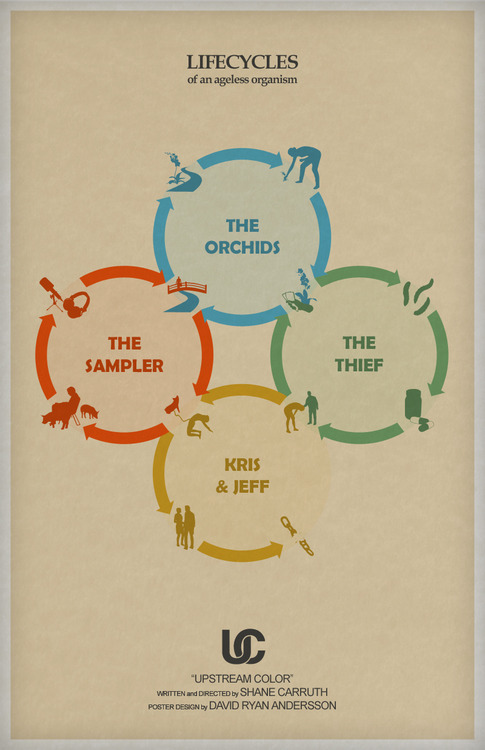

The second film from Shane Carruth –following his brilliant debut Primer nearly a decade ago (also available on Instant Watch)– Upstream Color spawned one of the most intriguing film conversations of the year as it debuted as Sundance, played SXSW, and then ran a course through a self-engineered theatrical and VOD release plan that involved no traditional distributor and, most importantly to Carruth, no compromises.

I saw Upstream Color at SXSW, wrote a weird review you can read here, and was lucky enough to arrange a substantial over-the-phone conversation with Carruth. I’m as pleased with this interview as any I’ve ever been a part of, so I hope you enjoy it. We discuss his through process on everything from distribution to acting as virtually every department head on his films to how likely (or not) it is that he’ll ever involve himself in Hollywood (spoiler alert: not gonna happen). Carruth’s is the kind of mind that is thoughtful and specific enough that I elaborated in my questions a bit more than usual, always knowing I’d be able to cut to something deeper and more specific and get a fantastically thoughtful answer from the filmmaker.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++

Renn Brown: So let’s start by talking a bit about the distribution model that you’ve come up with for this one…

Shane Carruth: Yeah. Basically, I started off just the same way I think, you know, anybody does when they’ve got a film. There’s Plan A, which is you try to get into a prestigious festival and maybe get some acquisition. Get the Focus [Features] deal. Get whatever. And that’s what everybody hopes for. Then you worry about: “Well, what’s Plan B? What if it doesn’t happen?” And so, I started thinking about Plan B the same way everybody else does. You know, at the beginning of last summer. And you know, I had been through distribution once with a distributor, and so I knew that more or less they hire out third parties to do some of the things they need, like theater booking and PR, and key art creation and stuff like that. So, I just went around just as a lark basically, just thought: “What if I was magically able to hire these people myself? And then I could make the high-level decisions. What would that look like?” And so I came to New York and I just started  going around and talking to people. And I don’t know. I sort of went: “Okay.” I sort of just walked into people’s offices and said, “This is what’s going to happen, so let’s talk about the mechanics of it.” And before long, it sort of seemed like it was possible. And then, I guess the other side of it – the business side – was the fact that I had a little bit of experience with using an aggregator to get into iTunes and all the other digital outlets that are available out there. So, I knew that that was, you know, not the biggest challenge in the world. It’s actually so much easier than it used to be with having to mass-produce DVDs and everything.

going around and talking to people. And I don’t know. I sort of went: “Okay.” I sort of just walked into people’s offices and said, “This is what’s going to happen, so let’s talk about the mechanics of it.” And before long, it sort of seemed like it was possible. And then, I guess the other side of it – the business side – was the fact that I had a little bit of experience with using an aggregator to get into iTunes and all the other digital outlets that are available out there. So, I knew that that was, you know, not the biggest challenge in the world. It’s actually so much easier than it used to be with having to mass-produce DVDs and everything.

Renn: Of course.

Shane: So, that’s sort of where it started. And then I think what really sealed it for me was the idea that it clicked for me that if I get to make these decisions that I get to contextualize the film exactly the way I believe it needs to be prepared for people. That you know, every trailer. The poster. Everything that anybody could come to understand something about the film before they actually sit in front of it, I can craft, and it starts to feel a lot like storytelling. My fear was that was a film Upstream — you know, a distributor can come along and they can say they get it. They could say they know how to sell this or whatever, but you know, if they decide they want to sell the story of blood and worms and pigs and horror, and thinking that’s going to make the most money, that’s what they’re going to do. And I’m not interested in that. I’m interested in making sure that people are receiving the work according to its ambition, and so I guess once that occurred to me it just seemed like: “Well, this is just going to have to happen.”

Renn: So I assume once the film had such an enthusiastic response at Sundance and kind of started accumulating traction, I assume you didn’t even entertain any offers or anything from any traditional studios?

Shane: I mean I pretty much shut down any conversations over a month before Sundance. I mean there was a plan put in place and it was to, you know, not spend a year trying to go to every possible festival that we could. That we were going to limit it and close – tighten up – the window so that we have sort of our coming out party at Sundance, but then by April, we’re in theaters. And I mean that was really informed by a lot of things. One, I want to be making another film. I don’t want to be traveling around with this one forever because I just don’t think it’s necessary. It’s like when I would be out in Dallas. You know, I’d hear about all these interesting films coming out at different festivals or whatever, but it’s like I would quickly put them out of my mind because, full well, I wasn’t going to see them for another year.

Renn: Right.

Shane: By the time they had a release of any kind, I would’ve already forgotten about them. I just didn’t want that to happen. I want to capitalize on this conversation. It’s weird. It’s weird to talk about because everything is part craft commercialism and part earnest storytelling.

Renn: Well, that’s filmmaking in general, I think.

Shane: Exactly. Exactly. Yeah, exactly. Wow, I’m glad you said that, because that’s exactly what it feels like. It’s, you know, you have to have the exploration and the literary gift, but then you also have to be compelling on a moment-by-moment basis. So, it’s the same way.

Renn: So, when you made this decision to do this kind of model and you were talking about – what I found intriguing – the idea that you can craft the contextualization of this film and the manner in which it’s going to be presented to people, tell me about your through process on that narrative for Upstream Color and how deeply you thought about it and how much, at this point, with the way film journalism works and everything, it’s largely a process of putting out pieces that then get snapped up and distributed at lightning speed. So tell me about working in that kind of thought process.

Renn: So, when you made this decision to do this kind of model and you were talking about – what I found intriguing – the idea that you can craft the contextualization of this film and the manner in which it’s going to be presented to people, tell me about your through process on that narrative for Upstream Color and how deeply you thought about it and how much, at this point, with the way film journalism works and everything, it’s largely a process of putting out pieces that then get snapped up and distributed at lightning speed. So tell me about working in that kind of thought process.

Shane: Do you mean that actual cutting of the material or deciding on the material, or do you mean like the politics behind getting it out there?

Renn: More like the cutting of the material. The imagery. The ways you released information.

Shane: Well, I always wanted to do a series of three [trailers] that we would — the first thing I wanted to do was just introduce the fact that this film exists. “Here’s some of the visuals that are involved.” “Here’s a little bit of texture.” But honestly all it was really ever going to do was sell the concept of being confounding in some way. That, “here comes a project. Here’s roughly what it looks like. And you can expect it to be challenging on some level,” because of the very teaser working that way. The next one was meant to be something that had no genre elements whatsoever. Like nothing that could be considered other worldly, and that was the second one that came out, and that was always meant to be something that just highlighted basically what’s on the emotional sleeve of this film. And I’d always thought of that one as sort of a gate. It’s like we’re not trying to — it’s not the idea that all awareness is good awareness. It’s that a certain type of awareness, letting people know. The people that are ready for this or want this – letting them know that it’s available, but not necessarily trying to sell it to everybody–

Shane: –and everything. So it was sort of like a gate and it says, “Look, we’ve got a narrative. We have a film and it has these confounding elements, and maybe things are a bit titillating, but at the same time, you’re also going to have to be okay with this sort of elliptical, emotional, subjective experience.” And so that’s what that was conveying. And then the last one – the actual trailer – was meant to be a combination of the two and just to sort of prove that these two things – these two ideas – can coexist in the same thing, and that’s roughly the identity of the film. But even then, you know, it’s not the most straightforward thing in the world. It’s definitely something that suggests, I think, everything that anybody would need to know about the film while pretty much not explaining the plot. And I mean that’s what I respond to. When I’m being prepared to sit down to view something, that’s what I want, and so that was the plan.

Renn: Fair enough. So, taking that idea that you’ve added this kind of almost marketer hat to the wide variety of roles that you play on your film and going back to kind of, I guess, the beginning, you’ve done starring, acting, writing, editing – the whole gamut. I’m interested, as filmmaker and as an artist you’ve done that now twice with your films. When you’re approaching all these roles, some of which are kind of very different from director to actor to composer – these things require engaging different parts of the brain and they work at different paces– do you compartmentalize your approach to the film in your different roles or is it all just one big “I know what I’m ultimately driving at” scenario and that just manifests every time a job or a problem comes up that you have to solve or do? I don’t know if that question makes any sense.

Shane: Yeah, it does. I don’t know if I’ve ever really thought of it, but that does make sense. It’s weird because it started off not having a plan. Just being a matter of necessity. And it’s now gotten to a different place, but I mean like I was talking about — like I started writing the music when I was writing the script, because it helps me write and it helps me have some confidence, and then we’ll be able to get to a specific moment and it will play roughly the way I’d like it to play. The music helps me know that I have that. I’ve got my storyboard and a few other things. I just I know something. I can live past it. And then, after a while, you know, the music starts to inform the writing, and when that happens, then it’s like I don’t think I could have the music necessarily wrestled from me at that point. I couldn’t hand it off to somebody else because I already know roughly what it should be. And the thing is I know I’m not the best composer in the world. I’m not the best at any of these things, but because they’re all having a conversation with each other, they become unified, at least in my head. And so, because of that, I just — my hope is that it makes the work more singular from the viewer’s perspective, and this is what I enjoy when I go and see a work that I believe is singular. In fact, if something’s challenging, you can have faith that it can be pulled apart and it will be purposeful and meaningful and point to the same thing, but it’s not something random. Like you don’t have to worry that the film is — you know, that it’s been rewritten by five different people and maybe whatever it is that’s challenging you is an artifact in the second rewrite that just got left in there. You know why things are there. And so, as an audience member, that’s what I respond to, and so when I’m crafting something, that’s what I want as well. Even if that means that it’s not going to be the world’s best music or the world’s best cinematography, or even the world’s best writing, but hopefully there’s some. I always say there’s an earnestest that arises if all of these things have the same voice.

Renn: Certainly. Well, by its very nature, filmmaking, you know, obviously has to be somewhat of a collaborative medium-

Shane: Absolutely.

Renn: So, where do you allow other’s creativity or other people’s decision-making to permeate your vision? It’s very singular as you said. I mean nobody’s going to deny that a Carruth movie is a Carruth movie, but by  its very nature, someone’s voice is going to have to peek in there, and how do you make that decision of where that’s going to be and where it’s not acceptable?

its very nature, someone’s voice is going to have to peek in there, and how do you make that decision of where that’s going to be and where it’s not acceptable?

Shane: It’s more or less — I mean everything I know about that I think I just learned on Upstream. And it’s basically just being able to find people that either, one, instinctively get what you’re doing or, two, are willing to have way more conversation that anybody should think of saying in order to get there. And what I could say about like Amy Seimetz is that I have seen her work as a writer/director and already felt like we were very close to understanding each other and how narrative works and how it’s meant to work. And so, I feel like ninety percent of any work we were going to have to do was already done because she’s a writer/director. She’d already been there. David Lowery, who helped edit – I did not know his work and I had no idea, and that was one of the most fortunate things in the world to be able to reach out to him for some help and him be able to just, without ego, satisfy exactly what needs to be done. And we, through conversation and through his work, quickly got to a level of real confidence and collaboration to where — I mean to this day I’m just really sort of surprised that he’s able to adapt so many different narrative styles, and especially this one. And then I would say, you know, Tom Walker, who’s a production designer. Everything about my confidence in him started with us having lots and lots of conversations of him doing a real analysis of what the work was trying to convey. You know, even when he was only maybe thinking about, you know, what should be hanging on the wall, I mean we were way deep into the idea of color symbolism. And he got that, and we had a roadmap. And so, I don’t know. When people are investing that much into something that I’ve written and they’re able to let it change them, and without ego at that, then I’m more than willing to just, you know, do the same in return. And I mean that’s roughly all I know about that. That it’s absolutely possible, and I guess that’s what it looks like.

Renn: So, circa Primer, you did an interview and said something that I found fascinating, where you talked about doing a gig just as a sound technician on a film and being kind of frustrated even on that indie level with the process of how much waiting there was and the logistical things that occur when you increase scale by any amount. And with Primer, you didn’t run into that because you were wearing so many hats and it was so contained. I know Upstream Color is still –relative to other things– small. A compact movie. But I have to imagine your logistics and scale increased at least a little bit on Upstream. So how did you keep a lid on, you know, your ability to control the pacing of your shoot and the intimacy of what you were doing, especially considering the tone and nature of the film?

Shane: Yeah, I would say, in general, the way that I did it was poorly. I don’t believe that this was an especially well produced film. Most of it is because I was rebelling against the way that film production typically works. You know, sometimes we find solutions that I believe are really interesting and good more than other times when, you know, not so much. Not so much. So, I don’t know. I mean I know that I wasted some people’s time and I did exactly what I didn’t like when I was, you know, volunteering and doing sound. And the only answer I can come up with is I have to raise money. I have to raise money, because you know, you pay for a film one way or the other. Either with money or time and sleepless nights, and I would like to pay for it with money next time.

Renn: So I guess you found there are certain parts of the wheel that cannot be reinvented?

Renn: So I guess you found there are certain parts of the wheel that cannot be reinvented?

Shane: Well, it’s weird. I still have that desire to reinvent them, but I’m learning about maybe where not to screw around. I mean I’m embedded in cinematography now. Like I will absolutely — I will technically be the DP, but that doesn’t mean that I need to be assembling camera every time or physically placing the lights. Like, I need to find a way to let that go. Come up with, you know, lighting schematics and let those be implemented while I attend to other things. But more times than not I become a log jam because I just — I haven’t solved how to — what’s the word? I don’t even know the word. That’s how foreign it is to me.

Renn: Haha, “delegate?”

Shane: Yeah, but I don’t know. There are lots of really wonderful things that happened in this as well. There’s a lot. I mean, you know, being able to grab a camera and go to a pool with Amy and shoot those scenes and not have thirty people standing around — that’s a pretty wonderful thing to be able to do. And so, you know, sometimes — that’s what I want to do this next time; is really have a good understanding and be able to understand where it is that we can go out in a small group and just solve this, and do really wonderful, you know, maybe luxurious work and be able to take our time. And then, where things need to ramp up. And we have a crew that’s big enough to handle, you know, the bigger logistics and stuff. I don’t know. I think it boils down to money and being able to hire people that know how to do this, and then ask them to revisit how they do it to maybe match what I’m used to. I don’t know. We’re solving it.

Renn: Fair enough. So you’ve got — you know, you’re kind of an anti-authoritarian figure. Almost like a quietly punk rock filmmaker, in a way. I think that’s fair to say.

Shane: Yeah.

Renn: And I’m wondering if your kind of distaste… “disinterest” may be a better word… in the whole Hollywood model and LA thing – does that run all the way to the very bottom deep, or area there ideas that you have that are big enough or playgrounds in which you like to work, or even toolboxes in that system that are interesting enough that could ever possibly entice you to work in that system?

Shane: Let me make sure. Are we talking about story?

Renn: Story. Technology. I mean, I doubt you have any interest in some 80’s kid property so much that you want to be the guy to make that movie, but you never know. Or if there are ideas that you just know are going to require a true Hollywood-scale production to pull off one day. I’m just curious kind of how deep that runs.

Shane: The thing is I don’t — I believe that there is so much momentum behind the way that things typically go that it’s difficult to have any part of how they do it out there without that affecting the whole. Like I know, full well, that I can’t ever go there for financing. Like that can’t happen because they think that if somebody has a checkbook that that person gets to say something about the story. That makes me want to come out of my skin. I simply don’t believe that. And that’s just the very first step on a really long journey that I know that I must be very egotistical to think that I don’t have to engage with that, but what I’ve learned is that they don’t want me any more than I want them. So it’s not like I’m rejecting them. There’s just no common ground and I would rather go dig a ditch with a spoon than dig a ditch with a tractor that they gave me.

Renn: Right.

Shane: I can’t seem to make that work. And you know, at every turn, if you had — I want to find a ways to make filmmaking easier on me and the people that I’m working with, but I think honestly we just need money. We just need money and we need to go out in the world and hire people to do stuff. We don’t need to engage a system or get involved with unions, or you know, deal with – I don’t know – any agencies or whatever.

Renn: With all the things you’ve done and the way you’ve so crafted and —engineered, I think is the better word– the way your films have been presented, and your own kind of personal imagine… I know I personally kind of had this impression of you, as a filmmaker that was… I don’t want to say inscrutable, but wasn’t necessarily going to give the audience anything or give people anything and wanted them to read it for themselves. But I’ve been kind of interested and intrigued by the way, at least with Upstream Color, in Q&As and different interviews and things like that, you seem to have at least some willingness to speak for the film and tell people your intentions and where you were going with that. So, tell me a little bit about that – how much you’re willing to let go and how much you’re not.

Renn: With all the things you’ve done and the way you’ve so crafted and —engineered, I think is the better word– the way your films have been presented, and your own kind of personal imagine… I know I personally kind of had this impression of you, as a filmmaker that was… I don’t want to say inscrutable, but wasn’t necessarily going to give the audience anything or give people anything and wanted them to read it for themselves. But I’ve been kind of interested and intrigued by the way, at least with Upstream Color, in Q&As and different interviews and things like that, you seem to have at least some willingness to speak for the film and tell people your intentions and where you were going with that. So, tell me a little bit about that – how much you’re willing to let go and how much you’re not.

Shane: Yeah, I mean that’s really interesting to me too, but the reality is, is that if I had money, I would be creating bits of media that would, you know, raise awareness of the film and maybe contextualize, but in a way that’s not the author talking. It’s in a way that’s like film. It’s in a visual and sonic media, and that’s the way that we deliver the context and what’s on the film’s mind. I don’t have that, so you know, we have to have thrifty, scrappy campaign, and that means to draw awareness of the film – the choice has been made that: “Great, I’ll do Q&As.” So then I find myself at a Q&A and in front of an audience of people that have been nice enough to show up, and are interested in the work, and nice enough to stay afterwards. So, at that point, it becomes really difficult for me to go: “I’m not going to talk about it. I’m not telling you guys anything,” because those are people — like even if an author necessarily shouldn’t be talking about the work right after the credits roll, these audiences are a bit unique. You know? Like they wouldn’t be there if they weren’t somehow in love with film on a more extreme level than typical. So, to me that means — you know, that’s starting to be closer to a camaraderie of people that are sort of embedded in the same world. And I guess, at that point, it just seems like: “Well, great. I’m not going to stand up here and act like I’m some pretentious obtuse guy that you guys have to figure it out.” Even though I would like the work to be so compelling that people would want to do that on their own, I guess I just feel like: “Let’s just cut through the crap and yeah, I’ll talk about it a little bit.” You know, just to sort of maybe prove that there is anything to talk about. And I don’t even know if that’s the right choice to be honest. I go back and forth as to whether that’s correct or not, but that’s where I’ve been.

Renn: I have to assume, with the nature of Upstream Color, that you have been presented with questions, or ideas, or interpretations that perhaps work on some entirely different level than what you were conceptualizing. Has that been the case?

Shane: Yeah, but very rarely. I mean no more than I’ve heard from other films that are, you know, straightforward. You know, there’s always somebody who’s — for example, somebody who’s very into, let’s say, vegan culture. And so, any time they see an animal on screen, they think that it’s about vegetarianism or veganism, or animal cruelty, or whatever else. That’s where their head is already, and so that’s where they go. So, yes, things like that do happen, but I would say that they’re like less than one percent of the time is somebody trying to say that the film was about this and I’m sure of it, but it’s some wild idea.

Renn: You’ve talked about your relationship during relationship with Primer and how you see a lot of the rough edges these days, even though it’s largely hailed as… well, I just have to imagine I’m not the first guy to come up to you after a screening and say that your movie changed my life. And if I was, I know I’m not going to be the last. So I’m curious what it’s like for you starting to enter that, where you’re now a decade out from Primer and you’re going to encountering people that have been affected by your movie for a long period of time, and now you’ve made another movie that is so specific and singular that it’s going to affect the people it affects in a very deep way. What is your relationship with that? What do you feel when you encounter that kind of thing?

Renn: You’ve talked about your relationship during relationship with Primer and how you see a lot of the rough edges these days, even though it’s largely hailed as… well, I just have to imagine I’m not the first guy to come up to you after a screening and say that your movie changed my life. And if I was, I know I’m not going to be the last. So I’m curious what it’s like for you starting to enter that, where you’re now a decade out from Primer and you’re going to encountering people that have been affected by your movie for a long period of time, and now you’ve made another movie that is so specific and singular that it’s going to affect the people it affects in a very deep way. What is your relationship with that? What do you feel when you encounter that kind of thing?

Shane: Wow, several things. Yeah, people do walk up to me and say pretty hyperbolic things about Primer afterwards. And I mean I’ve been so surprised because I didn’t- You know, I’m so glad the film was received the way that it was back when it back out. I didn’t understand that, at least on a small level that there were kids that were maybe like thirteen when that came out, but have now grown up since then basically and are in film school or whatever and have been affected by it. I actually don’t even know how to process that. It’s I mean obviously a very — I don’t know what the word is for it. It’s a very good thing; a positive thing. It feels pretty wonderful, but I don’t know exactly how to address it. I feel really strongly about Upstream. I know that it’s not — you know, not everything about it is technically perfect, but I just think it’s a really strong work and a work that I hope will have a long life, because I think it’s worth of it. And it’s weird because, you know, I’m not secure really in Primer. I’m not necessarily secure in myself, but this is a film that I just think very good things about. So, I don’t know. I guess I do expect that people will be affected by Upstream for some time to come, or at least anybody who’s like me, because it’s exactly the sort of film that I would latch onto and enjoy.

Renn: So, with Primer, you had a film seemingly built on this almost mathematical language. This engineering-specific rigidity. And now you have Upstream and it’s built on this poetic romance and this lushness. And it’s clearly from the same mind, but speaking with a different kind of language. I wouldn’t say they’re on the opposite ends of a pole, but kind of opposite sides of the same miasma. I don’t know. But tell me about moving from that. Was that a conscious choice to do something so different, or was that just a natural evolution of where you are all these years later?

Shane: Yeah, I mean I guess it would have to be, because it’s definitely a rejection or reaction to Primer. It is what it needs to be. You know, with the story essentially about people being affected by something that they can’t really speak to, and so that requires a lot of nonverbal communication and a lot of the tools that can be used in the film to convey that. You know, using all of them as effectively as possible. So, it’s a more subjective experience, and so that’s going to mean that it’s more emotional or hopefully more emotional. So it starts with what’s the exploration, and then that dictates sort of the language how to get there. There’s also the missing piece, which is A Topiary, which exists in my head, but I can’t show it to anybody. And I think if people could see it, they would see that it was potentially a middle step between the two in a way that I know — like I mean the thing that I’m writing now is taking a lot of the language of Upstream and pushing it even further as far as — I don’t know. I guess I hope you haven’t read this before, because I know I’ve said this before. I don’t know how to switch it up, but I just think of there’s the exploration and then that dictates the story and how the story works. So I would take all of that and I would put that in the word “architecture.” I think of that part of this as architecture. That’s the part that’s really solid or hopefully solid. And that you could take that bit and you could repurpose it in a bunch of other forms. Maybe not even film. Maybe other ways. You know, forms of narrative in the same way that you could take the tortoise and the hare or three little pigs, or whatever. Like things that are rudimentary building blocks of narrative, and they can be repurposed in all these other different forms. That’s the way I think of the core of Upstream; is that the architecture, I find, I hope, is really, really sound. So then the execution of the film is more impressionistic and more lyrical, and it’s finding where the edges of the architecture are by just much more – I don’t know – humanistic and lyrical, and less precise, and subjective, and impressionistic, and all the ways that you could sort of swim around the solid object and understand how it works without necessarily, you know, showing the CAD design of it. And so I guess that’s the way I think of Upstream and that’s the way I — an exaggerated version of that is what I think of the next film.

Renn: Architects have certainly made a lot of beautiful, expressive, varying kinds of buildings from very similar, rigid architectures.

Shane: Exactly. Yeah.

Renn: So, I have to imagine with Upstream that it’s the kind of film that– they say you write a film three times when you write it and shoot it, solve problems, and then cut it. Would you say that’s the case with Upstream? How much of this did you find in the edit, or was it frame-ready in your mind when you sat down to do so?

Shane: Yeah, it’s really tough because this was all, you know, departments having a conversation with each other. Okay, Susan’s like giving me the three fingers. Two or three fingers, or whatever that means.

Renn: No problem.

Shane: Three minutes. Okay. Basically I didn’t want — I wasn’t trying to do this, but this is what happened on this film. That I wanted to know everything there was to know about everything in the writing process, and then, you know, assemble everybody and we’re like: “Hey guys, here’s what we’re doing. Let’s go do it.” And I have had to recognize that that’s not the way for film to get to its height. That’s maybe only a way to have a book that you could watch. And I want film to reach higher than that or reach to something more appropriate and find out what it’s actually capable of. And I think the only way to really do that is to allow all of these things to have a conversation with each other. You know, I was talking about the script writing, and then the music being a reaction to that, but then letting the writing be a reaction the music. And then, let’s talk about what’s our visual language. And in this film, that said something about the music, and I ended up having to throw out half the music and regrow it in a more subjective material way to match what we were accomplishing, I think, really effectively visually. And then that said something about — you know, that went back to the script and said, “Well, wait, some of these scenes have dialogue that is redundant because I believe we are communicating this both visually and with the music,” and so great, let’s talk about that. And then that affects everything. It becomes this big storm of information, and so next time around – and this is what I’m doing now when I’m writing – I just want to know that from the get-go. Like, I don’t want to figure that out along the way or as we get close to production. I want to know that right now in this moment, and so I don’t know what that means and I don’t know how to necessarily prepare for it.

Renn: Do you think that’s possible? Do you think even if you go forth and do all the work and thinking to kind of anticipate that, that other new things that you couldn’t have predicted will emerge on top of it?

Renn: Do you think that’s possible? Do you think even if you go forth and do all the work and thinking to kind of anticipate that, that other new things that you couldn’t have predicted will emerge on top of it?

Shane: Well, I don’t know. I think, hopefully, what makes it possible is being open to it and being a little bit more technically proficient each time. I mean I know a lot more about what I’m capable of in cinematography and in music now than I did last year. And so now I know where my tool set is a little bit better so I know where I can rely on it. And I know — here’s the thing: I’m going to keep making mistakes. I do this all the time, but hopefully I’m making less mistakes. And for me, the biggest hurdle in the world is to decide when is it time to step away from this department and go to this one and see what the reaction is, and the move from there to there. I don’t know. It’s pretty hard to verbalize. I just know that it’s important that we maybe not give up completely, but try to dismiss a little bit this notion of things being in building blocks. That there’s a writing process. There’s a preproduction. There’s a production process. And there’s a post, and then you have a movie. I think that’s going to have to, in some way, get a little bit more flexible.

And there you have it! Thanks for reading!