[Note: In true Luhrmann style, this one is rather indulgent. Perhaps it’s for those that would like a review with some, “surplus flesh” as Fitzgerald would put it.]

It’s no spoiler to mention that Baz Luhrmann chooses to end his adaptation of one of the most examined and widely-read American novels ever written with an image of the book’s manuscript- specifically its title page. The Great Gatsby is in first-person after all, so its narrator Nick Carraway must have written this all down at some point, justifying Luhrmann’s framing device of Carraway actually telling the story aloud. On this manuscript page, “GATSBY” sits alone and singular on a plain, cream-colored page before a hand enters the frame to scrawl “The Great” above it.

And there you have it, intended or not- 100 years of academic examination, pup-cultural impact, and distressingly resonate literary subtext all captured in a shot at the end of a moving picture.

Fitzgerald wrote about the man Gatsby in the early 20s, and in the century since he has become a massive figure, a literary icon. Shorthand for the American dreamer. The man with the talent and ambition inextricably linked with the obsession and unquenchable hunger that ensures success will never be enjoyed, if it doesn’t lead to one’s outright destruction. On top of that icon though, we’ve spent as many decades as we all have fingers affixing mystique and romance, condemnation and celebration to the man in the palace at West Egg. A handful of film and TV adaptations, countless novels alluding to or outright adapting the story to other settings, and a US literary curriculum spotlighting the novel has meant that most of us have contemplated the greatness of Gatsby at one point or another.

Enter Baz Luhrmann, who ends his film with a hand scrawling “The Great” above the character’s name. It’s a reminder that in the novel itself, Gatsby’s introduction is not in slow-motion, that Nick Carraway does not initially read the subtext of all that is wrong with the American dream in his encounters with the guy. Instead he’s merely an interesting character, a person. An ALL-CAPS character to be sure, but still a flesh and blood figure that Fitzgerald chose to label “Great” on the outside of the novel, sparking an irony vs. earnestness debate that storms on to this day. In fact, in 2013 it’s as relevant as ever. Gatsby would have been called a “job creator,” after all.

Enter Baz Luhrmann, who ends his film with a hand scrawling “The Great” above the character’s name. It’s a reminder that in the novel itself, Gatsby’s introduction is not in slow-motion, that Nick Carraway does not initially read the subtext of all that is wrong with the American dream in his encounters with the guy. Instead he’s merely an interesting character, a person. An ALL-CAPS character to be sure, but still a flesh and blood figure that Fitzgerald chose to label “Great” on the outside of the novel, sparking an irony vs. earnestness debate that storms on to this day. In fact, in 2013 it’s as relevant as ever. Gatsby would have been called a “job creator,” after all.

All of this rich literary context is captured in the final moments of Luhrmann’s film, and yet in true Luhrmann style it punctuates a film that is rarely about any of those things. Like pretty much all of Luhrmann’s work, The Great Gatsby 2013 is about a romance that is just not going to work out. The director is laser-focused on the agony and the ecstasy of obsessive love- that kind of love so wrapped up in lust, ego, and a dozen other primal human feelings that it becomes a physical ache in one’s soul and is shared by 16 and 60-year-olds alike. It’s also that kind of love connected on some deep level with our desires to break out of whatever circumstances we’re in, or perhaps even to break out of who we are. It’s the kind of love that makes it clear just how arbitrary and escapable the setup of our lives can be, despite how profoundly rare it is that we ever escape it.

The best scenes in The Great Gatsby capture these moments. Dinner at the Buchanan’s. Gatsby and Daisy’s reunion in Nick’s house. Gatsby’s fixation on the green light. The awkward lunch before everything spirals out of control.

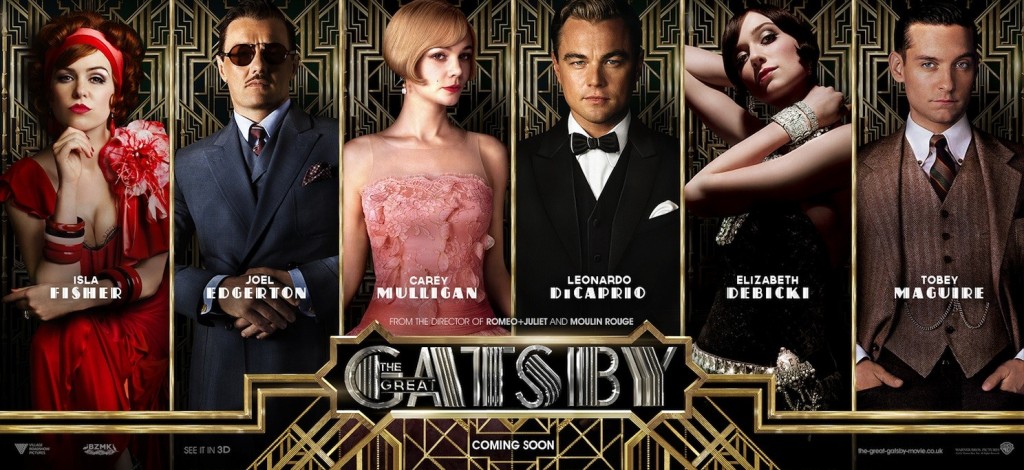

Lurhmann wouldn’t be successful if he weren’t working with actors capable of bringing new life to old characters, and he chose well for this one. Dicaprio has become a figure big enough for Gatsby –we feel something when he comes on screen– and so he doesn’t have to force Gatsby’s “cool.” Nor does he shy away from a vocal affectation that is as Fitzgerald described it, just short of “absurd.” I have to imagine it’s a tough act to calibrate the tone of your performance to fit into Luhrmann’s circus without seeing the whole thing, but Dicaprio pulls it off. The cool is there, but more importantly he sells Gatsby’s irrational need to wholly consume Daisy- truly the key to everything.

Lurhmann wouldn’t be successful if he weren’t working with actors capable of bringing new life to old characters, and he chose well for this one. Dicaprio has become a figure big enough for Gatsby –we feel something when he comes on screen– and so he doesn’t have to force Gatsby’s “cool.” Nor does he shy away from a vocal affectation that is as Fitzgerald described it, just short of “absurd.” I have to imagine it’s a tough act to calibrate the tone of your performance to fit into Luhrmann’s circus without seeing the whole thing, but Dicaprio pulls it off. The cool is there, but more importantly he sells Gatsby’s irrational need to wholly consume Daisy- truly the key to everything.

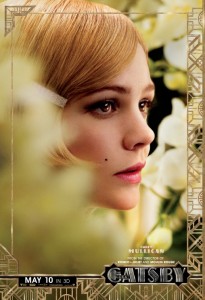

Mulligan is perhaps most deserving of kudos for crafting an interpretation of Daisy that is tragic rather than merely irritating. Many seems to miss the self-effacing irony even in the novel of Daisy’s declarations that she’s “done everything,” and the sadness in her hope that her daughter is no more than a “beautiful little fool.” Mulligan sells it, meanwhile offering a stunning face for Luhrmann to fetishize. She also captures the unpredictable flights of poetry in Fitzgerald’s text, which is prone to describing Daisy’s voice or manner or walk with all sorts of fancy prose that would be rather difficult to distill into an actual performance for a less skilled actor.

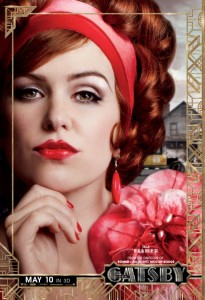

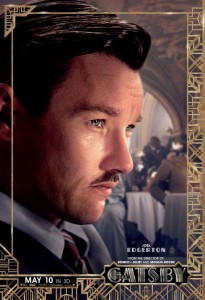

Joel Edgerton is simply great. Isla Fischer, Adelaide Clemmons and several other beautiful ladies fit into Luhrmann’s sexy spectacle, with varying degrees of fidelity to the novel. With Luhrmann uninterested in making hateful spectacles out of these more thoughtless characters, they largely serve as the means to overwhelm Nick Carraway. That said, Elizabeth Debicki does some fine work as Jordan Baker- the other voyeuristic presence alongside Nick in the lives of Gatsby and the Buchanan’s.

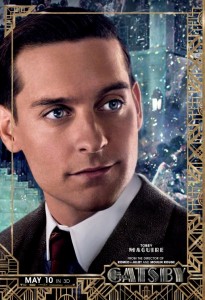

Now in the later half of his 30s, Tobey Maguire’s unassuming manner has become marbled with maturity. There’s still that sadness though- the hint that beneath the sweetness is a pretty ugly temper, or at least a deep pool of cynicism. It makes Maguire a great choice of Carraway, our disaffected entry point into this story.

Now in the later half of his 30s, Tobey Maguire’s unassuming manner has become marbled with maturity. There’s still that sadness though- the hint that beneath the sweetness is a pretty ugly temper, or at least a deep pool of cynicism. It makes Maguire a great choice of Carraway, our disaffected entry point into this story.

Interestingly, Luhrmann’s Carraway says all of the same things as Fitzgerald’s about being disgusted with New York and hating everyone but Gatsby, but with Maguire you sense that he doesn’t necessarily believe it. There’s too much beauty and fascination in his recall of the events for us to all the way buy his disillusionment. It’s one of the many ways in which the judgemental tone that Fitzgerald’s work is known for simply doesn’t translate to Luhrmann’s world. Even if it’s key to The Great Gatsby being maintained as the great, post-industrial Great American Novel, Fitzgerald’s condemning attitude is a flashlight being shone into the raging sun that is this director’s fascination with ill-fated love.

Baz Luhrmann is often talked down to something of a cinematic wedding planner, but for all his fixation on set dressing and costume, he knows how to craft a scene full of tension, be it sexual or social. His melodrama works when it must, justifying all the times it plays merely as indulgence. The drama of The Great Gatsby –the Shakespearean longing to character’s have for one another– is often overlooked as people trip over themselves to hate the detached Daisy, or to write another essay on the broken American dream or whatever. But these are very much human beings populating this story- ones with feelings we’ve all felt and that Luhrmann renders with the kind of hope and despair that can’t be accomplished when irony and judgement is one’s key concern. He’s also very much concerned with capturing Fitzgerald’s uniquely descriptive tone, and he often manages it. A famous description of a room full of flowing curtains that contribute to the magic of meeting Daisy becomes a legitimately beautiful, exact replica of what one might imagine in one’s head. That happens a few times.

But more strikingly this is a film that empathizes with its characters rather than examining them, which pushes all of that chewy “American dream” subtext into the background. It’s exactly what you would expect Luhrmann to do, but it does remind us that even in a novel as acutely examined and relatively widely-“understood” as The Great Gatsby there is still a story at its heart. In the anticipation of the film there’s been a weird sense of a goalpost out there suggesting Luhrmann has failed or “missed the point” if he does not turn that subtext we’re all familiar with into outright text, and I’m not so sure that’s fair.

But more strikingly this is a film that empathizes with its characters rather than examining them, which pushes all of that chewy “American dream” subtext into the background. It’s exactly what you would expect Luhrmann to do, but it does remind us that even in a novel as acutely examined and relatively widely-“understood” as The Great Gatsby there is still a story at its heart. In the anticipation of the film there’s been a weird sense of a goalpost out there suggesting Luhrmann has failed or “missed the point” if he does not turn that subtext we’re all familiar with into outright text, and I’m not so sure that’s fair.

My tendency is to give filmmakers the benefit of the doubt, and in the face of the extended partying sequences and ostentatious 3D there is plenty of evidence that Luhrmann “gets it.” Along with the final image mentioned above, there are a handful of really great moments in which Luhrmann nails a key visual from the story, or invents his own. The dock’s green light is the most familiar of the book’s images and one of the most effective of the film, though the famous bespectacled billboard comes off as much more clunky and obvious. Luhrmann sometimes digs out new imagery in the attempt to capture Fitzgerald’s contemplative tangets, including one in which he exploits 3D to draw us into the windows of New York, each with their own story.

To get to the city, the East and West Eggers pass through the ash fields where the most downtrodden Americans do the nastiest labor imaginable- it’s also where Tom Buchanan stops in to scoop up his mistress from her dullard husband. It’s not the most subtle of Fitzgerald’s juxtapositions, and yet when Luhrmann gets ahold of it he does something interesting. He fixates his camera on a resting African-American man, who is sweaty, strong, and entirely unconcerned with the rich people moving past. There’s nothing as obvious as the poor shooting rich people looks- just the suggestion that all Americans are wrapped up in their own context. It’s a throwaway image, but one that has stuck with me.

Technically the film is gorgeous. The CGI and compositing are good enough that Luhrmann’s zooming camera and digitally recreated set pieces aren’t any more distracting than anything else happening in this densely-packed film. The parties are of course heightened to the point of absurdity, but they’re also designed in a way that fits with Nick Carraway remembering them. I was struck by the library Carraway and Baker peek into to meet the Owl-Eye man- atop a mountain of books are a dozen perfectly filled martini glasses planted and waiting. It’s the kind of detail that one adds to a memory after 20 years, or perhaps adds into a story to make it grander. And since “Gatsby Parties” have long been a thing, it’s not unjustified for Luhrmann to go all-in with these sequences to try and sell the awe that Nick Carraway feels in the face of Gatsby’s wealth.

Technically the film is gorgeous. The CGI and compositing are good enough that Luhrmann’s zooming camera and digitally recreated set pieces aren’t any more distracting than anything else happening in this densely-packed film. The parties are of course heightened to the point of absurdity, but they’re also designed in a way that fits with Nick Carraway remembering them. I was struck by the library Carraway and Baker peek into to meet the Owl-Eye man- atop a mountain of books are a dozen perfectly filled martini glasses planted and waiting. It’s the kind of detail that one adds to a memory after 20 years, or perhaps adds into a story to make it grander. And since “Gatsby Parties” have long been a thing, it’s not unjustified for Luhrmann to go all-in with these sequences to try and sell the awe that Nick Carraway feels in the face of Gatsby’s wealth.

Less successful are Luhrmann and Jay-Z’s needledrops, or at least the more ostentatious ones. Much of the anachronistic music works fine, but little is gained when an insubstantial remix of “No Church In The Wild” plays out over archival footage. I’m intrigued by the idea of giving a hip hop coating to a Great Gatsby film that otherwise maintains fidelity to the source material, but it doesn’t amount to much here.

Appropriately enough I’ve reached a point of indulgence where I simply have to call it. The Great Gatsby is compromised, interesting, silly, potent, earnest, highly artificial, and fun all at once. It would seem to be a love-it-or-hate-it proposition, and yet I suspect there will be a lot of shades of both love and hate for it. Luhrmann’s spectacle is too pretty too miss, his command of individual scenes too sophisticated to dismiss, but his fixation on doomed romance is too shallow to fully embrace. It’s a film of contradictions, a film of simultaneously admirable and dubious ambition. Appropriate enough for an adaptation of one of the great American novels, I suppose.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars