“It is not about naturalism.” – Interview with the BBC June 28 2001

Baz Luhrmann does not make movies for the faint or the terminally-cynical of heart. He makes movies for those who, like him, revel in outsized emotion, broad caricature, frenetic movement, bold design, rampant sensualism, outright camp and intentional artifice.

…This is a very specific subset of people. You either fall for his particular brand of excess or you’re left cold and/or hostile toward it. His approach/attack countenances little in the way of middle ground.

One gets the sense watching Luhrmann’s films that he’s more than a little unhinged, and utterly intoxicated by the process of creation. Being around someone who’s intoxicated is a lot more fun when you’re intoxicated also. If you’re not? Well, then being around them can be a crushing, frustrating bore. That’s true of emotional intoxication as well. If you can’t get on Luhrmann’s giddy/heady wavelength you’re not going to like his films. More than that – you’re probably going to resent them.

Luhrmann’s idiosyncratic artistic tics have earned him the ire of critics who see little in the way of “real” emotion in his films and who accuse him of valuing aesthetics over emotion, artificiality over naturalism, as if those things were, in and of themselves, sins to be atoned for. Compounding the issue is the fact that Luhrmann’s movies aren’t really “intellectual” affairs; they’re largely sensual ones, and Luhrmann’s ideal of sensuousness very often comes coupled to rampant, ludicrously exuberant excess. It’s not enough that Moulin Rouge’s Christian and Satine sing, dance and fall in love – they must do it on top of a giant plaster elephant while the moon itself sings down on them. It’s not enough for Australia’s the Drover to deal with stampeding cattle – he must deal with a digital army of cattle that threaten to spill over the world’s largest cliff. It’s not enough that Romeo & Juliet’s titular couple lock eyes electrically for the first time – they need to do so through a multi-colored curtain of tropical fish. Luhrmann doesn’t so much gild the lily as he encases the lily in an ornate golden block and paints that block a different, brighter shade of gold.

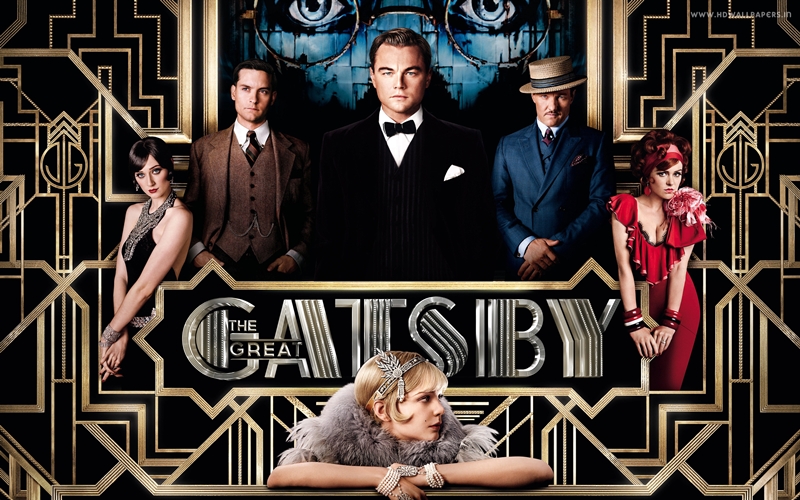

…Which is why I tend to think he’s pretty much the perfect person to adapt The Great Gatsby. Luhrmann’s style is uniquely suited to communicating both the sumptuousness and the emptiness at the heart of the novel and the time period. His operatic inclinations, his unabashed romanticism, his ravenous hunger for sensation, make him an ideal conduit for a story set amid the roiling, extravagant time in which Fitzgerald’s novel takes place. He was made to capture the wanton excess of the “flapper era” with his camera; to convey the clashing, diametrically-opposed condemnation and admiration of elegant excess that so permeates Fitzgerald’s book. And while the novel has passed into that great sterile void of Respectability where all classic literature goes in order to be dreaded by high schoolers, Fitzgerald’s tale also crackles with exactly the same sort of melodramatic power that Luhrmann has reached for, and occasionally grasped, over the whole of his career.

The title of this piece comes from Fitzgerald’s novel, and the passage it comes from strikes me as a good example of why a florid stylist like Luhrmann is such an inspired choice to attempt a new adaptation:

“The exhilarating ripple of her voice was a wild tonic in the rain. I had to follow the sound of it for a moment, up and down, with my ear alone, before any words came through. A damp streak of hair lay like a dash of blue paint across her cheek, and her hand was wet with glistening drops as I took it to help her from the car.”

Fitzgerald uses words here like Luhrmann uses imagery – to intoxicate and evoke a verdant, somehow-ominous sensuality; to paint using vibrant slashes of feeling. The much-mocked decision to film the book in 3-D is, I think, a stroke of (mad) genius. What better way to further invite the audience to participate in the obscene opulence on display, to inhabit the same rarified air as these characters? 3-D offers a visual, sensual means of giving the story literal depth, even as the story itself in its original form more-or-less refuses us that particular luxury among its many luxuries. For all the praise heaped upon Fitzgerald’s undeniably captivating prose, it’s difficult to argue that the characters who populate his story possess real depth, dimension, or complexity. The book’s characters aren’t really characters so much as they’re archetypes – vessels to convey the author’s thoughts and beliefs. Their artificial nature, and the melodramatic machinations of the book’s plot, are fertile ground for Lurhmann’s unique muse.

Luhrmannn, by his own admission and design, has used artifice and melodrama in his films in an attempt to get at deeper, unabashedly sincere truths. It’s fair to say, I think, that he’s on a quest to transcend melodrama through melodrama He has spoken at length in the past of his desire to circumvent the modern era’s cynicism and its rejection of the kind of sincerity more readily accepted in earlier eras by utilizing in his films the same ironic distance many people carry with them into the theater. Moulin Rouge, his riff on the myth of Orpheus, is perhaps the most potent example of this particular approach. The first 15-20 minutes of that film pummels the audience with rapid-fire editing, insane spectacle, whip-quick tone shifts and bizarre behavior in an effort to evoke the whirligig-freneticism of Luhrmann’s imagined Montmartre, France during a period of artistic, social and cultural upheaval. It’s frankly exhausting, and it’s definitely not for everyone.

It’s only once the film’s Euridice stand-in, the luminous Satine (Nicole Kidman, rarely more appealing), descends from the heavens and into the underworld awash in cold blue light that the film slows to take a breath. By then all of that flash and dazzle has had its desired effect (or so I’d argue). Luhrmann has taken an era with the potential to come across as sepia-toned and unrelatable and made it hyper-real, primally emotional and dizzingly playful. That initial furious energy works to disarm the audience through sheer force of artistic will, and demands that they sit up and pay attention or get the hell out. In an era chock-a-block with technically-accomplished visual stylists Luhrmann stands apart – because he clearly doesn’t give a flying fig whether you choose the former or the latter. He’d like you to come along, populist that he is, but he’s not about to tone down his party if the neighbors start complaining.

And just as the Moulin Rouge and the general historical era it resides in proved an apt muse and a fitting canvas for Luhrmannn’s particular obsessions, so too the roaring twenties of Gatsby. We have a tendency as a culture to view history as a succession of still life tableaus, and ever-receding decades with a kind of bemused paternalism. This is often simply because most of us don’t remember history very well, or bother to know it very intimately. Here in the present we eye our ancestors like butterflies under glass. We tend to deny them the vibrancy, excitement, violence, passions and quirks of our own existences. The roaring twenties is a perfect example of that tendency. We cast our gazes back and expect refinement, black tie cocktail parties governed by restraint and Victorian mores. But the 20’s were anything but a stuffy, airless period piece. Luhrmann’s demented approach feels, sight unseen, like the perfect approach to adapting a book that has famously resisted successful adaptation. Luhrmann doesn’t want to show you a picture of the era. He wants to shove your face through the picture, and that instinct seems like the right one in terms of making Gatsby feel like something other than a stultifying period piece; a bejeweled and glamorous fly trapped in amber-colored celluloid.

On May 10th, Baz Luhrmann is throwing a big, lavishly themed party, and he’s gonna get wasted on art and melodrama and sensual pizzazz. He’d like it if we joined him. He’ll pop the champagne, bring in the girls and boys, crank up the band, and then try to devastate us in the dark. I don’t know that he’ll succeed, but I do know that it’s a party I want to be a part of.