The film: 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

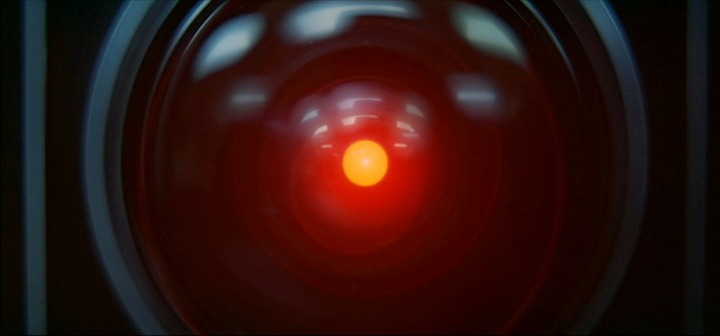

The Principals: Stanley Kubrick (director). Keir Dullea (Dr. Dave Bowman), Gary Lockwood (Dr. Frank Poole), William Sylvester (Dr. Heywood Floyd), Douglas Rain (HAL 9000).

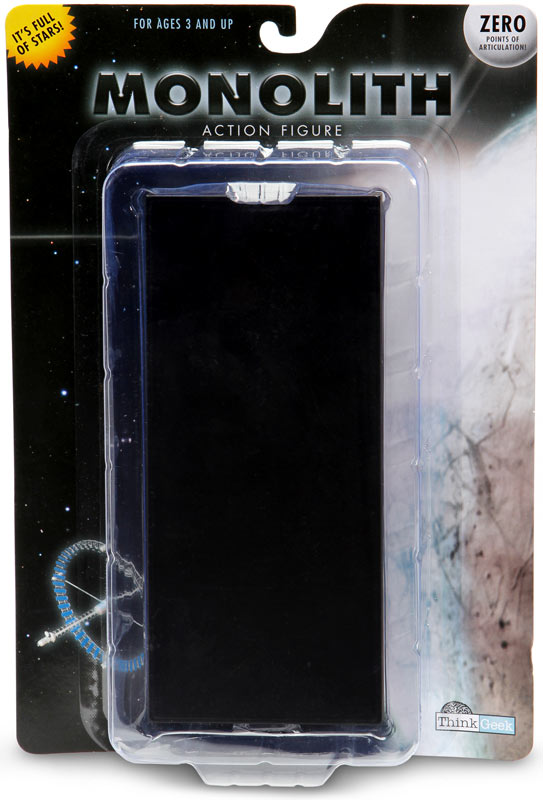

The Premise: The synopsis on Amazon states that it’s “about a space voyage to Jupiter that turns chaotic when a computer enhanced with artificial intelligence takes over”. On its simplest levels, this is true. But that’s really only one single component of a much larger, grander film. This is a film that examines existentialism, human nature, the universe, and our place in it. Who are we? How did we get to where we are now? Did we have help? What else is out there? These are all questions posed by the film, as well as the source material. The film doesn’t intend to answer any of these questions. Instead, it takes us on a journey of exploration and discovery, allowing us to investigate and postulate on what it puts on display. We’re then given the chance to formulate our own ideas and conclusions. Also, there are some cool, black rectangles that look ominous and do crazy things – like jump start evolution and take astronauts on mind-blowing spacid trips.

The Ebert Principle: Upon doing a search of Ebert’s musings on 2001: A Space Odyssey, I immediately found three articles he wrote about the film. His first article was written in April of 1968, right after the movie was released. It is a short, but fantastic review of the film. His use of language is just as eloquent then as it was up to his passing. In fact, there’s a poetry to the way he describes the film and how it connected with him. He seems extremely fascinated with this movie, almost on a spiritual level.

The second article is a thorough break-down and analysis of 2001 and the meaning behind the monolith. I found his words here to be especially poignant and thought-provoking, as he deconstructs the movie down to its basic elements and goes on to answer the questions posed by the film (or not answer them, as he points out that we don’t always need the answers handed to us). He comes off a bit condescending, but it’s not difficult to understand why – his second article is written almost off the heels of his original review, and notes specifically his irritation at how the film was not well-received by his fellow viewers. From there, he examines why the casual movie-goer would not be as receptive of 2001, while at the same time trying to explain why they need to evolve as film viewers in order to be able to embrace films of that caliber. At that point, Ebert’s message is the same as the film’s – we need to evolve and transcend what we know and are used to.

His third article was written in March of 1997. It’s an updated review of the movie that includes his experience with the rest of the attendees either not getting the film, getting confused and/or angry with the film, or just straight-up walking out. He then reiterates what he believes is the reason why not everyone comes away from the movie embracing it like he did, then explains what is there to embrace:

“The film did not provide the clear narrative and easy entertainment cues the audience expected. The closing sequences, with the astronaut inexplicably finding himself in a bedroom somewhere beyond Jupiter, were baffling. The overnight Hollywood judgment was that Kubrick had become derailed, that in his obsession with effects and set pieces, he had failed to make a movie.

What he had actually done was make a philosophical statement about man’s place in the universe, using images as those before him had used words, music or prayer. And he had made it in a way that invited us to contemplate it — not to experience it vicariously as entertainment, as we might in a good conventional science-fiction film, but to stand outside it as a philosopher might, and think about it.”

What’s impressive about this article is how a man is able to write about the same movie more than once, years apart, restate all of the same observances, break-downs, and admonishments, and yet still make it sound unique and fresh. One thing that has tuck in my mind throughout all the research I’ve done for this article is that it almost seems like Roger Ebert was exactly what he saw in 2001 – a man who has learned how to evolve and advance past his craft.

Is It Good? It would probably be damning for me to argue with one Mr. Roger Ebert, especially since this week’s MoD column is meant to pay tribute to the man. In fact, I think there might even be a special hell for folks who can’t at least acknowledge the intelligence and insight Ebert had at the same time that they dismiss his reviews. That said, whether or not 2001: A Space Odyssey is one of the top ten greatest films is certainly up for debate. In fact, it should be debated. Otherwise, you miss one of the major points of a film of this caliber. Regardless of what side of the argument you find yourself on, is it a good film? It’s universally agreed upon that it is, and not just because of what Kubrick brought to the screen. No, 2001 has become bigger than the sum of its parts. It’s the grand scale of the story being told. It’s the artistic use of imagery, music, and lack of dialogue. It’s the imagination and scope of a message being imparted. It’s a parable – as Ebert put it. But it’s also the legacy behind it. 2001 made a huge impact on the film industry after its release in 1968, and continues to influence modern filmmaking today. From directors to special effect to tone and artistic influence, this film has managed to touch the industry on multiple levels. It’s even gone outside the boundaries of just film making, influencing technology and even culture. When a film has an impact that wide and large, it’s almost impossible not to agree that 2001 is a good film. And yet, there are still people who think it’s just a boring, crappy flick. And there’s nothing wrong with that. But I think for a movie like this you get what you give. Some movies require little to no nothing from us as viewers in order to enjoy them and be entertained. Most of the time, all we have to do is sit in the seat, relax, and watch as the images and sounds unfold on our very faces while we consume large quantities of overpriced concessions. But some films require more effort. They require us to do some of the work ourselves to make that connection to what the film is trying to offer. We have to invest, turn on our brains, and allow the movie to inspire us to think and contemplate what we’re taking in.

Is It Worth a Look? There’s no question. This is a film designed for folks to observe, then think and talk about afterwards. 2001 is art – pure and simple. If one could hang this in a museum, I feel like it would fit in perfectly on the wall next to the Picassos, the Rembrandts, and the van Goghs. Anyone who watches this movie will take something away from it, even if it something as simple as “It was long and boring.” But that’s art. Some people look at a piece and it connects to them on a personal level. Others will look at the same piece and be turned off by it completely, as they cannot relate to it on any level. But either way, the point of any piece of art is to elicit some kind of response, good or bad. 2001 is no exception. One of the things I discovered during my viewing and preparation for this article is that though the film seems to go off the rails into random insanity, it actually does make a kind of sense. It’s just that Kubrick didn’t include the map. Though the film is certainly art, it’s also a puzzle – much like the puzzle of the monoliths that the crew of the Odyssey tries to solve in the movie. The clues to figuring out and understanding 2001 lie not only in the clues that related outside media can provide – articles, books, “Making’s of”, interviews, the source novel – but also from contemplating the film and discussing it with others. It’s like DaVinci Code done right – you pick up more pieces to the puzzle as you go, which in turn opens your eyes to the complete picture. This makes the experience of 2001: A Space Odyssey much more than just watching the film. The movie is only the gateway into a larger journey of discovery and wonder. Isn’t that worth a look?

Random Anecdotes: Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke collaborated on both the film, as well as the novel. Kubrick met with Clarke after he expressed a fascination with extraterrestrial life and wanted to do an epic space-adventure film. Clarke has gone on to admit that Kubrick should have gotten co-authorship for the novel, stating that the movie was by “Kubrick and Clarke”, while the novel was by “Clarke and Kubrick”.

Ebert would go on to give the sequel 2010 a favourable review as well, stating that it was a good film, but viewed best if separated from the far superior predecessor.

Nerd-tchotchke website Think Geek once offered an “action figure” of the Monolith from 2001 on their site. Originally an April Fool’s joke, they eventually produced real ones for purchase after getting a large amount of fan demand for it. I own one.

Cinematic Soulmates: Moon. Sunshine. Solaris. The Fountain. Star Trek: The Motion Picture. Prometheus.