The Film: The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

The Principals: Nicolas Roeg (director), Paul Mayersberg (screenplay), Walter Tevis (source novel), David Bowie, Candy Clark, Rip Torn, Buck Henry

The Premise: An alien comes to our planet, founds a billion-dollar corporation, and tries to adapt to American life. (Working title: The Mitt Romney Story.)

Is it any good? I can honestly say that I’ve never seen anything like it – and while it continually held my interest, it’s not necessarily an easy watch. It’s incumbent on the viewer to keep up with consistent, jarring tonal shifts, edits that span days, years, and geography without warning, a large cast of characters that weave in and out of the narrative, flashbacks and detours to Bowie’s character’s home planet, and montage sequences chock-full of ‘70’s acid-trip weirdness.

The plot starts out simply enough – Thomas James Newton (Bowie) falls from the sky and crash-lands in a lake, Icarus-style. After wandering around in a hoodie for awhile (thankfully, he didn’t land in Florida), we discover that he brought a British passport, a wad of cash, and a stack of new, viable electronic patents with him. With the help of lawyer Buck Henry, Newton builds a massive corporation through innovations in remarkably prescient fields like self-developing photography and renewable energy; with the endgame of making enough money for Newton to get back home to his wife and small children and to bring water to his dying, drought-stricken planet. The Man Who Fell to Earth is, basically, the story of what happens to Newton as he’s busy making other plans … and the effect that humanity has on this odd, fragile hero.

I don’t want to write too much about the plot – one of the best things about this movie is its unpredictability and sense of discovery – but I will touch on some of my favorite moments: The opening shots showing Newton’s descent into the lake (including an aerial shot that recalls Sam Raimi’s board-cam from the original Evil Dead). Bowie’s subtle acting with his face and eyes as Candy Clark talks about her belief in God (and then minutes later, in church, as he struggles to follow along with the hymnal). The relationship that develops between Newton and Rip Torn’s cynical scientist, and the scene that takes place between them in Newton’s spaceship. Newton’s brief glimpse into America’s past. A sequence midway through the film that is legitimately frightening when Newton’s lover (Clark) discovers his true nature. A moment when Newton is asked about his children, and he answers with poignant simplicity. Another scene late in the film that … well, imagine how harrowing Clockwork Orange would be if you actually liked Alex DeLarge. And an ending that – given everything we’ve seen before – is both heartbreaking and note-perfect. Frankly, the more I write, the more scenes I remember and want to tell you about; and I already want to watch the film again if only to pick up on things I missed.

I don’t want to write too much about the plot – one of the best things about this movie is its unpredictability and sense of discovery – but I will touch on some of my favorite moments: The opening shots showing Newton’s descent into the lake (including an aerial shot that recalls Sam Raimi’s board-cam from the original Evil Dead). Bowie’s subtle acting with his face and eyes as Candy Clark talks about her belief in God (and then minutes later, in church, as he struggles to follow along with the hymnal). The relationship that develops between Newton and Rip Torn’s cynical scientist, and the scene that takes place between them in Newton’s spaceship. Newton’s brief glimpse into America’s past. A sequence midway through the film that is legitimately frightening when Newton’s lover (Clark) discovers his true nature. A moment when Newton is asked about his children, and he answers with poignant simplicity. Another scene late in the film that … well, imagine how harrowing Clockwork Orange would be if you actually liked Alex DeLarge. And an ending that – given everything we’ve seen before – is both heartbreaking and note-perfect. Frankly, the more I write, the more scenes I remember and want to tell you about; and I already want to watch the film again if only to pick up on things I missed.

So yes – it’s good.

Any discussion of the film is incomplete without mentioning the involvement of its two principals, Bowie and director Roeg. Roeg’s camera is always moving, his edits are precise and fluid, and he always nails the small moments that make the whole flick more than the sum of its parts. There are echoes of Malick, Kubrick, and Spielberg here, but the overall film is one none of them could’ve made without erring too far into scenery, cynicism, or sentimentality. That Roeg is able to balance so many disparate tones (and to make us care about characters drawn mostly in broad strokes) is a massive accomplishment.

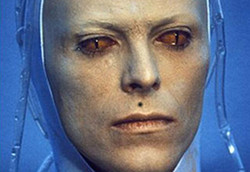

Without a doubt, Roeg’s best decision was the casting of Bowie. Even with the benefit of hindsight, it’s difficult to see where Bowie ends and Newton begins. His natural androgyny and sense of otherness serve the character, but Bowie restrains his natural swagger enough to imbue Newton with vulnerability and humanity. This is his defining film role, his Indiana Jones, and the fact that this was his first film performance is jaw-dropping (especially given the fact that he was apparently high as a cocaine-fuelled spaceship for the production’s duration).

Is it worth a look? If you’re not sold yet, then the movie’s probably not for you. Everyone else … seek it out.

Random anecdotes: Captain James Lovell of Apollo 13 fame shows up briefly as himself.

As stated above, Bowie admits to being strung out for the duration of production. He later said “I just threw my real self into that movie as I was at that time … I was going a lot on instinct, and my instinct was pretty dissipated. … I actually was feeling as alienated as that character was. It was a pretty natural performance.”

The film was cut by almost twenty minutes for its original American re-release. All of the footage has been recovered, and re-edited back into the Criterion DVD/Blu-Ray.

Walter Tevis – the writer of the novel that inspired the movie – also wrote the novels The Hustler and The Color of Money.

Cinematic Soulmates: ET. Starman. The Day the Earth Stood Still. Definitely not Signs.