As craft, Atonement is astonishing. There is no denying that Joe Wright is one of the most visionary and gifted directors working today. His name would certainly be tripping off the tongue of CHUD readers as often as that other, equally talented, Wright if his chosen genre to date wasn’t romance films. And he has assembled a first rate cast who give their all in a movie that is beautiful, thoughtful and endlessly compelling.

As craft, Atonement is astonishing. There is no denying that Joe Wright is one of the most visionary and gifted directors working today. His name would certainly be tripping off the tongue of CHUD readers as often as that other, equally talented, Wright if his chosen genre to date wasn’t romance films. And he has assembled a first rate cast who give their all in a movie that is beautiful, thoughtful and endlessly compelling.

Which makes it all that much weirder that I never connected with it on any emotional level. Atonement is a movie meant to send you into the theater lobby with puffy red eyes and tear stained cheeks, and technically it does everything it needs to do to get that reaction from you. But it’s that technical proficiency that made it impossible for me to feel the film; I stand in awe of it, I admire the hell out of it, but it never touched me or resonated within me in any deep, meaningful way.

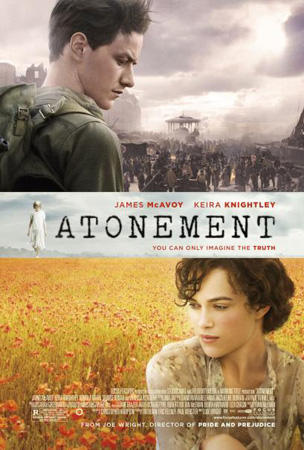

An adaptation of Ian McEwan’s postmodern novel, Atonement is a movie whose twists and turns are hardwired into the plot in such a way as to make any basic synopsis a spoilerfest. Suffice it to say that the movie moves from a British manorhouse to the World War II ravaged landscape of France as it tells the story of two soulmates kept apart by a young girl’s terrible misunderstanding… or lie. Keira Knightley and James McAvoy play the young lovers, and you want to root for them just so they can get together and have the most beautiful children imaginable. Three actresses play the girl – the magnificent Saoirse Ronan at age 13, Romola Garai at 18 and Vanessa Redgrave at the end of her life. While the movie is about the two lovers, the real main character is this girl, Briony. Wright has lucked out in a major way with Ronan, whose performance is one of the greatest I’ve seen a child actor give. Knightley and McAvoy are also wonderful (now that the Pirates movies are over maybe people can start accepting Knightley as a great actress), and Redgrave gives a touching performance as someone at the end of her life dealing with the major mistakes she has made, and her inability to ever set them right. Across the board Atonement is a finely acted piece.

It’s also gorgeous. Even the war scenes have a ragged beauty. And for a two hour and ten minute film, Atonement flies by at a brisk pace, never stopping, always moving forward with its characters and stories. Maybe that’s part of the problem I had with getting in touch with the film: its third act feels like an epilogue and so the film feels like it has no second act, like there’s a big chunk of emotional development we’re being asked to take for granted.

But I think my problems with the movie are summed up in the already legendary Dunkirk evacuation tracking shot. In Pride & Prejudice Wright slips in a stunning tracking shot during a party scene, but it’s stunning because of how he sneaks it in – after a little while you realize that what you’ve been watching is one continuous take. In Atonement this beach scene might as well open with a title card: "And now for the tracking shot!" Which isn’t to take away from the virtuosic artistry that went into bringing this complex and layered scene to life, but I found myself feeling like a punk rocker listening to ELO in the 70s – you have to admit this shit is really, really well made, but what purpose does it serve other than to let you know how well they can make this shit?

By the time the movie got to its twisty metafictional ending (which just doesn’t work as well in a film as it does in a book. Here’s why, invisotexted for the spoilerphobes: The idea of using events from reality and changing them, making the outcomes different, is much more palpable in novels than it is in films. Films rarely feel as personal as a novel because there are so many people giving input; the writer may be taking an event from his life and playing with it, but that event then must go through the filter of the producers and the director and finally the actors. Only in the most indie, smallest movies does the feeling of their being a direct statement from filmmaker to film viewer come through in the same way as it does in many novels. Of course Wright doesn’t try to make Briony into a filmmaker and keeps her a writer, but I have always felt that writer is about the worst and most vague job for a movie character. In a novel a writer works because we’re immersed in words in a way that we’re not in a movie – we’re constantly reminded in a novel what a writer’s world is and how it works. It’s too abstract for film, which does better with painters and other visual artists) I was engaged enough to feel very bummed out by what happened, but never reached that transcendent weepy moment that I was longing for the whole time.

Special notice must be taken of Dario Marianelli’s score, which is phenomenal. I don’t usually pay a ton of attention to scores, but Marianelli uses the sound of a typewriter in his music to tie in with the film’s larger metafictional themes. Right from the start the music is there to clue you in to the bigger picture. This is your Best Score winner.

Atonement is, in the end, mildly disappointing, a movie that is beautiful but without warmth. Hopefully Joe Wright can continue on the visual path he is blazing for himself while not again losing the humanity of his wonderful Pride & Prejudice.