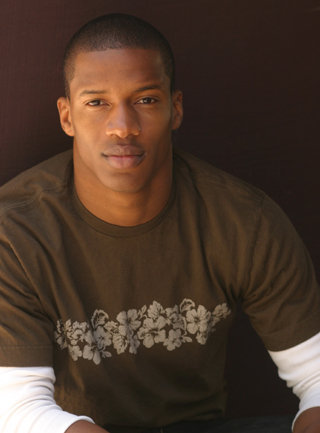

When the invite for The Great Debaters press day hit my inbox, I made two immediate requests: 1:1 interviews with Denzel Washington and Nate Parker. I was fairly certain that Denzel would decline, but, hey, it never hurts to ask. As for Nate, whom I’d never seen in anything before, I was going on the early enthusiasm for his performance as Henry Lowe, a young Lothario whose intellect is as outsized as his libido. If I couldn’t talk with Denzel, I figured I’d take a shot at chatting with a kid who just could be the next Denzel.

When the invite for The Great Debaters press day hit my inbox, I made two immediate requests: 1:1 interviews with Denzel Washington and Nate Parker. I was fairly certain that Denzel would decline, but, hey, it never hurts to ask. As for Nate, whom I’d never seen in anything before, I was going on the early enthusiasm for his performance as Henry Lowe, a young Lothario whose intellect is as outsized as his libido. If I couldn’t talk with Denzel, I figured I’d take a shot at chatting with a kid who just could be the next Denzel.

Then I saw the movie and realized that if I didn’t get Nate Parker now, I’d probably have a very hard time getting him on the next one. From his first scene, which finds him brawling outside a backwoods gin joint with the razor-wielding husband of a woman he was just romancing, there’s little doubt about Parker. He’s got the same volatile combination of charisma, sex appeal and simmering rage that made Paul Newman one of the biggest movie stars in Hollywood history. And, come to think of it, I guess he’s also a lot like Denzel, too.

When I sat down with Parker in his suite at The Four Seasons a few weeks ago, I was certain we’d cover the Denzel subject thoroughly. I was not, however, prepared for him to bring up Newman on his own, even though, in retrospect, it makes perfect sense. Parker’s the kind of movie star – just concede it already – who’s too driven and too aware of the rules of the game to fail; in this respect, he reminds me of Tom Cruise (only better behaved on Oprah). He’s not the type to talk about how fleeting fame can be, and how he’s just happy to be here. No, Parker’s the kind of guy who’s talking career, dropping names like Newman, Denzel, Poitier and Robeson, and convincing you he’ll have that kind of impact even though he’s got an Uwe Boll movie opening next year.

Parker’s not the only reason to see The Great Debaters, but he’s all you’ll be talking about afterwards. And the confidence exuded in the below interview should make this piercingly clear.

Q: I know that you’re probably getting a lot of this, but I have to say that the way that you carry yourself onscreen – the swagger, the confidence – reminds me of Denzel right when he was coming into his own with films like Cry Freedom, Glory and The Mighty Quinn. When you get cast by Denzel Washington to play a role like this, do you feel the weight of these expectations?

Nate Parker: I feel more of a responsibility. I got the script two years ago, before anyone had become a part of it, and it spoke to me instantly. And once it did, I said, "Okay, I’m going to prepare for this whether I’m going to be in it or not. This is going to be something that I attach myself to." So I learned all the speeches; I learned everything. I learned the whole script, and then I began writing. I wrote a 100-page biography that I gave to [Denzel] when I met him at the audition. It was very important to me to prepare. And once I prepared to look this man in the eye and let him know that I’m a professional, that this is about collaboration… I thought everyone would walk in and be like, "Hey, Training Day, you were very good," or "Hey, before we start, I just want you to know that you’re my idol." I wanted him to understand that I took this as serious as he did. That I had a knowledge from the research that I had done on this character, and that I may have known Henry Lowe better than he did. So I wrote and I wrote and I wrote. And I read James Joyce. I read D.H. Lawrence. I read W.B. Yeats. I read Countee Cullen. I read Langston Hughes. Because I wanted to be able to open my mouth and be knowledgeable about the script. All of that chipped away at that wall that was in front of me. It chipped it away so that when I got to sit down and talk to Denzel Washington, it was like we’re talking right now.

Q: Did you talk before the audition?

Parker: No, no! When I walked in, I was very adamant about starting the audition right away. Because I didn’t want to seem gimmicky; I didn’t want to come off as a fan. I was very adamant about making him feel that I wanted to be a professional. That I looked up to him to the point where I wouldn’t even insult him by trying to make small talk. I remember like it was yesterday: I walked in, and I saw him. He said, "How are you?" I said, "How are you? I’m Nate. Shall we work?" And he said, "Yes, we shall." In his Denzel voice! And we started right away. We dove right into it: he pulled some scenes out of the script, and we were reading over each other’s shoulder. Then, at the end of the read, I gave him my 100-page biography that I’d wrote because I read an article that he requires a biography of the character. I gave it to him, and he said, "What’s this?" I said, "I read an article that said you require a biography." And he said, "Good." And the rest is history. He calls himself "The King of Research"; I want to be known as "The Prince".

He has some very big, polished shoes to fill, but never would I insult him by saying "I want to be Denzel Washington." But what I will say is, "I pray that in thirty-five years, I can look back on my body of work and be proud of it."

Q: While you’re trying to do things the way Denzel likes to do them, isn’t there a concern that "I’ve also got to be myself?" Like you don’t want to come on too strong, just confident?

Parker: Absolutely. And Henry Lowe is a picture of confidence. Like you said, on one hand I understood that the only thing that matters is my preparation – not that casting director, not the director, not the producers. If it was John Doe directing, it would be no different than if it was Denzel Washington. That’s what I told myself. I’m not going in there to wow Denzel Washington; I’m coming in as a professional to speak the truth of this character.

Q: So when you get to the set, and you’re verbally going toe-to-toe with Denzel Washington, were you able to maintain this level of professionalism?

Q: So when you get to the set, and you’re verbally going toe-to-toe with Denzel Washington, were you able to maintain this level of professionalism?

Parker: You know what it was? I felt like Denzel was my father. My father passed away a long time ago, and [Denzel] was very much a father figure and a mentor. He was also very much a brother, a friend and a collaborator. I never felt that "Academy Award winning" presence. I always felt like he was approachable, like he trusted my research, and, no matter what, that he wanted me to succeed. He’d do two takes of himself, and he would do as many takes as we wanted until we felt good. He didn’t care about the film or the cost. He didn’t say, "Check the gate." He would look at us and say, "Are you okay? How do you feel about this?" And that took so much pressure off. It took off this pressure of feeling like you have to hit it in one take and do it great. You know what I mean? He wouldn’t tell you what to do or [give you line readings]. He come over and whisper something into your ear. He’d say, "How do you feel about yesterday?" – and yesterday would’ve been the lynching scene. So you’d talk about that scene. Or he’d say, "What do you think about Samantha? She looked beautiful today, didn’t she?" It would remind you of just how beautiful she was, so when we went out to do the boat scene, you would take all of her in. And you’d be like, "Oh, my gosh, she looks so beautiful." You’re not being given a note, which means "Change this!" You’re reminded of who you are, where you are, what’s the truth and how to deliver the truth – all in the suggestion of a thought.

Q: That’s great. Way back when I used to direct actors in college, I always found that it’s about the use of imagery. You have to engage their imagination. And once you do that, then you get to play. With so many film directors, it’s like "You’re getting three takes. We’ve got to make a day."

Parker: "Light’s coming. You better get it." Then there’s that pressure of not only worrying about being vulnerable and giving off the truth of this character, but also the externals. With Denzel, it’s all about the internal. The externals don’t matter. If you flub a line, he always says, "It doesn’t matter. Who cares? Let’s go. You just do what you do." He made this film an actor’s medium. The way Denzel explains it, "Theater is a actor’s medium, but film is a director’s medium." In a play, when you’re on that stage you can do whatever you want to do. Whereas in a film, the second the director doesn’t like what you’re doing, it’s like, "No, no, no. Let’s fix it." But Denzel being such a theater buff, and I might be stretching a bit… I would assume that he leans toward that actor’s medium of theater in his directing. Letting the actors’ research and preparation speak in the scene.

Q: How much theater did you do before you got into film?

Parker: Nothing. I started acting four years ago. It was freak how I got into acting. I went to college on a wrestling scholarship, was an All-American and got a job as a desktop publisher. One day, a friend of mine went down to Dallas for an audition, and I just came along for the ride. And this guy approached me and said, "Are you an actor?" I said, "No." He said, "Are you a model?" I said, "No." He said, "Read this monologue." So I read it. Then he said, "Okay, read it again in front of all these people." I said, "Okay," and did it. Then he said, "You must move to L.A." I put in my two weeks notice at work, and, fourteen days later, I was sleeping on his couch.

I don’t have any theater background. My acting coach is my manager. He taught me what he knows, and he’s very good at what he does. He taught me how to make yourself vulnerable to the character, and how important the truth is to that character. That’s all I have. That’s my background. I do plan to get into theater, if only for the simple fact that Denzel said, "It’s important to learn your craft." So when I get time in the future, I plan to get involved with Broadway.

Q: When you did that first reading, did you have that sense that most actors feel? That "getting bitten by the bug"?

Parker: Yes. It’s for the rest of my life. I would rather be a homeless actor than a powerful, rich politician. It speaks volumes about doing what makes you happy. And I love what I do. I love it so much.

Q: Did you ever consider being an actor when you were younger?

Parker: Not at all! And everyone in my family tells me that I was an actor even back then. I was a performer. I loved telling jokes and standing up in front of the family. It was just something that I wasn’t exposed to, so I never did it. But once I was exposed to it, I pursued it like I did wrestling: I prayed a lot and prepared a lot. And I’ve been blessed.

Q: Coming to acting that late and realizing it’s all you wanted to do, that must’ve been pretty powerful.

Q: Coming to acting that late and realizing it’s all you wanted to do, that must’ve been pretty powerful.

Parker: It’s interesting. The second I began acting, I realized it was what I was meant to do all along. Wrestling was just something that prepared me; it gave me the discipline, it gave me the patience, and it gave me the sacrifice that enables me now to be in this business. Because it takes sacrifice. I don’t go out, I don’t smoke, I don’t drink, I’m very conscious of the things that I eat, and I work out every day. All of these things that go along with acting are things that I got from other levels of my life, whether it be high school or meeting my step-dad in the Air Force and traveling around. Or in wrestling, where I learned competition – the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat.

Q: That’s good. They say an actor’s body is his instrument. I think a lot of male actors think they can get away with being out of shape.

Parker: At the end of the day, you could work. I’m learning in Hollywood that anybody can work. You can get a commercial here and there, or a job here and there. But the point is a career. If this is truly what a person wants to do, there should be nothing in the world that could deter them. It’s like with anything else. I want to be an actor, but what does that mean? Do I want to be acting in ten years, twenty years, thirty years? Do I want to act until I can’t act anymore? Look at Paul Newman, who’s another one of my heroes. I read that he stopped acting because he couldn’t remember his lines. But he did it until he couldn’t do it anymore. How great is that? I’m living a dream. A lot of people don’t get to do what I do, and I take it very seriously. I’m all about giving up the truth of the character. Whoever the character is, they have a truth.

Q: Whenever I hear an actor talking in such detail about having a career, I’m convinced that it’s going to happen.

Parker: It’s absolutely going to happen. But even now, we’re not taking everything that’s thrown at us. We’re really trying to shape my career. Like I said before, you look at Denzel Washington and the choices that he’s made… they’re really big, polished shoes to follow. And I’m trudging behind with a big shovel. I’d love to one day fill his shoes. And if I can one day look back and be proud of what I’ve done, then I’ve done something. So we’re being very careful of the projects we take.

Q: You mentioned Paul Newman. Any other actors’ careers that you’d like to emulate?

Parker: Yes. Sidney Poitier and Paul Robeson.

Q: Wow.

Parker: These are legends in this business that, in spite of their environment, persevered above so much resistance. These are my heroes.

Q: Robeson makes sense. He was an athlete. He had a great mind and was very political.

Parker: He was an orator and a debater. It’s a funny thing. I’ll show you something really quick. (Nate gets up, strides into the adjoining room in his suite, and emerges with his Blackberry.) I’m a graphic designer. And this is my screensaver for my computer. I look at it every day. (He shows me the screen, which displays four floating heads over a black background.) That’s Poitier, Robeson, myself and Denzel. Every day I look at it. Every time I answer the phone I see it. These are the people who made a way for me. They’ve given me the responsibility of carrying their torch. This is my life, and I take it very seriously. It’s about having a career. Hopefully, in ten years, you’ll want to interview me.

In ten years, I’ll be lucky if you’ll take my question at a press conference, Nate.

The Great Debaters opens Christmas Day in limited release.