The Golden Compass is an extraordinary movie for one bad reason: it manages to be both rushed and boring at the same time. The film blows forward at a breakneck pace but never thinks to make anything happening on screen in the least bit interesting. By the end of the movie you feel like you’ve been watching a very long, very dull sketched outline of something bigger, meatier and more meaningful.

The Golden Compass is an extraordinary movie for one bad reason: it manages to be both rushed and boring at the same time. The film blows forward at a breakneck pace but never thinks to make anything happening on screen in the least bit interesting. By the end of the movie you feel like you’ve been watching a very long, very dull sketched outline of something bigger, meatier and more meaningful.

Phillip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy is philosophy and theology based young adult fantasy. It’s not Harry Potter and it’s not Lord of the Rings; in many ways His Dark Materials is one of the few truly original fantasy stories of our time. I’ve read the books and while I can’t say I’m a fan of them or Pullman’s writing, I found myself intrigued by his big ideas and the way he dared take his story and his characters in strange and dangerous directions. But while I was reading the books I couldn’t find the cinema in them: Pullman’s story is just a skeleton upon which to hang his musings on gnostic beliefs and the nature of reality, free will and sin. Those musings are thought-provoking, but I would often find myself wanting to fast forward through his storytelling to get to his ideas.

The Golden Compass (known as The Northern Lights in the UK), the first in the series, is the slightest of them all when it comes to big ideas. Here Pullman sets up his universe, a world where people’s souls live outside their bodies as totemistic animal projections known as daemons, where a strange particle known as Dust connects parallel worlds and where a fascist Church controls people’s lives and thoughts. The plot of The Golden Compass defies easy synopsis, and the movie version feels like someone trying to make that synopsis. The major story and mythology points are hit, and we’re introduced to all the characters, but the audience never feels engaged in anyone or their journey or their struggles.

The film’s journey takes us from the grounds of Oxford College, where orphan Lyra Belacqua gets caught up in events larger than herself (she’s one of those prophecied about types of kids that always show up in these stories), to the polar north, with barely a stop for breath each step along the way. Director Chris Weitz ruthlessly moves the story forward, but he doesn’t give us the chance to ever give a shit; when Lyra first leaves Oxford to live with the glamorous but evil Ms. Coulter (Nicole Kidman, and my understanding is that the name was not originally a reference to Ann – but Kidman’s blonde hair, different from the book, may be) we get the excitement of living in high society presented as a 45 second montage before Coulter’s evil surfaces. There’s no opportunity for us to feel the sting of betrayal Lyra must feel. This happens again and again – the movie barrels forward and we’re introduced to character after character but never given a reason to care about what happens to them.

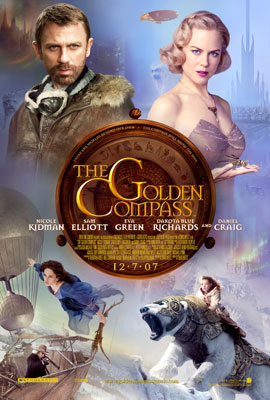

The characters drop into the film all throughout, some so abruptly as to be comical. The ever-gorgeous Eva Green appears as the witch Serafina Pekkala, who just lands on the deck of a ship on which Lyra is traveling, delivers some exposition and takes off until the very end of the movie. It’s loopy that anyone could have watched this scene and thought that it flowed or worked or that it gave us any understanding of Pekkala. Again and again characters show up, state things that the audience or the characters must know to keep the film going, and then either disappear or stand around in the background until they’re again needed to deliver information or take an action. Sam Eliott is perhaps the most egregious example of this; perfectly cast as the American balloonist Lee Scoresby, Elliott spends most of his screentime just hanging around. Of course this is fairly faithful to the book – Scoresby has more to do in the sequel – but these are the kinds of issues screenwriters are expected to iron out.

Because of this the whole movie feels like it’s on rails, progressing from one scene to the next without the actual participation of the main characters. On top of that, the stakes feel constantly low; we learn that children are being kidnapped by ‘Gobblers’ for mysterious purposes, but this information is told to us, not shown to us. By the time we do see a Gobbler kidnapping it’s quick and over too soon – there’s no feeling of menace here. As it was in the book, most of the details about the Gobblers and what they’re doing are saved for the end. By the time we get to see (or actually just be told, like everything else in this film) what the Gobblers are up to, we don’t care anymore.

The early footage from The Golden Compass showed laughable FX work. The good news is that the FX in the finished film is almost uniformly superior, especially the daemons (although why they needed to CGI in almost every single animal in the movie is baffling. You could have shaved 100 million off the budget with the judicious use of animal trainers), which are often photoreal. Where the FX falter is in portraying vistas, which always look fake, and in the polar bear sequences. In these scenes the actress playing Lyra is the only real world element – everything else is computer generated – and the whole thing looks like an update of Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, with the girls’ realness sticking out like a sore thumb.

Dakota Blue Richards is the girl playing young heroine Lyra Belacqua, and she’s actually quite good – although like everyone else in the film she has nothing to do the whole movie. Beneath all of that standing around passively, though, is a potentially fiery screen presence. Daniel Craig shows up just long enough to collect a paycheck, and I suppose he’s fine in the role. The only actor who seems to have anything to do is Kidman, whose increasingly plasticine features work very well for her vain, self-centered character. Kidman manages to exude an icy menace, but also gives the most embarrassing reaction shot I’ve ever seen a professional give. Look for it in the scene when her daemon gets its hand caught in a window. The worst bit of casting comes when the voice of Ian McKellan pours from the mouth of CGI polar bear Iorek Byrnison. When introduced the character is supposed to be a dissolute drunk, but with McKellan’s voice he just sounds really old.

Director Chris Weitz dropped out of the film years ago because he thought he couldn’t do this story justice. Turns out he was right; as a director he’s competent but doesn’t have ‘sweeping epic’ in him. The Golden Compass is often visually flat and, as the action moves north, feels increasingly stagebound. Someone said to me that the opening five minutes of the film, which includes a shot where the camera moves through a rip in reality, is the most visually interesting bit of the whole two hours and I have to agree. Weitz is obviously working in less than ideal circumstances when half his story takes place in snowy wastes, but David Lean managed to make the desert look interesting in Lawrence of Arabia.

That seems like an unfair comparison, but I don’t think it is at all. These big fantasy epic movies are the modern day version of the Lawrences of Arabia – although in The Golden Compass’ case, maybe we should be looking at Cleopatra. We should be holding these movies to exceptionally high standards; they should entertain and also move, they should be spectacles not just in terms of the processing power of the CGI rendering workstations but in cinematography. The problem is that computer imagery isn’t breathtaking, isn’t amazing. Despite costing 250 million dollars, The Golden Compass feels small, contained, hemmed in on every side. The physics of the daemons’ hair follicles is impeccable, but everything bigger is dull. The Golden Compass, like so many of its ilk, is a micro movie, one that focuses on the minutia and leaves the macro stuff – the hugeness that a story like this demands – off the table. The movie is the work of technicians, not artists.

All of that said, Weitz should be commended for keeping Pullman’s thematic elements intact. While the Church has become a more generic Magisterium, the ideas of disobedience and questioning authority remain intact. The Golden Compass is the least theological of the books, and Weitz plays down what little religion there was in the first place while keeping the door open for the second and third books, which are far less subtle in their critiques. I hope for this film to be a success only so that I can see how New Line and Weitz deals with blatant gnostic theology and bald faced anti-Church sentiment in the sequels.