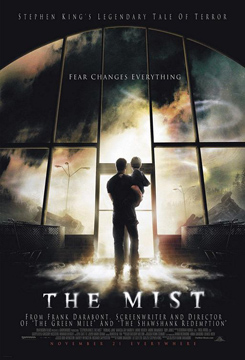

Frank Darabont’s The Mist

Frank Darabont’s The Mist

is far from a flawless work: its first act relies on contrived conflict

to set its ideologically (and theologically) diverse characters against

each other; the basic conventions of the narrative will be overly

familiar to anyone who’s seen "The Monsters are Due on Maple Street";

and, on a strictly superficial level, the sub-$20 million budget is

hell on the special effects. Of these shortcomings, it’s the latter

that will most heavily tax the viewer’s suspension of disbelief. And

it’s not really their fault; mainstream audiences should hardly be

expected to excuse a film’s budget when they’re passing over $10-plus

per ticket.

This is a highly precarious concession, but one that

was evidently required to bring the Stephen King novella – first

published in the 1980 horror omnibus Dark Forces, and, subsequently, in 1985’s Skeleton Crew

– to the big screen. It’s important to keep this in mind as Darabont’s

film introduces its stock dramatis personae and gets them talking past

each other as the mist rolls in over a small town supermarket bustling

with activity in the aftermath of a massive thunderstorm. And it’s

especially important to keep those allowances coming during the film’s

first creature attack, in which a completely unconvincing CG tentacle

wreaks havoc in the store’s stockroom. In fact, one might as well just

diminish their expectations for everything prior to the arrival of the

winged bugs ballyhooed by the film’s aggressive ad campaign (which

must’ve cost as much as the movie itself). Because that’s when The Mist starts paying off.

In a way, The Mist‘s

uncertain first act works to its advantage; those unacquainted with the

story will let their guard down, figuring that Darabont is up to

nothing more than a junky creature feature larded with classic Twilight Zone/Playhouse 90 pretensions. But attentive viewers might sense that the sentimentalist of The Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile is up to something a little nastier than usual when Darabont’s camera lingers longer than necessary on a recreated poster of John Carpenter’s The Thing.

It’s supposed to be the work of David Drayton (Thomas Jane), a

beleaguered movie poster artist whose latest assignment is wiped out

when the aforementioned storm blows a branch through his workshop

window. And Darabont further invites comparisons to Carpenter’s classic

by introducing David’s long-standing conflict with his African-American

neighbor, Brent Norton (Andre Braugher).

But the storm seems

to have engendered a détente between the two men: i.e. since Brent’s

luxury auto was crushed in the storm, David offers to drive his

erstwhile rival into town. This is misdirection, of course, but

Darabont plays the scène à faire

as more than a cold function of the plot; as David and Brent warily

exchange small talk (with David’s young son, Billy, serving as a

civility buffer), it’s clear that contentiousness is only one

ill-considered utterance away. This isn’t rapprochement; it’s just a

practical, temporary cease fire.

Once the men arrive at the

supermarket, the rest of the world floods in, and it’s a whole lotta

microcosm. Though all small towns are uneasy jumbles of class and

intellect, Darabont exacerbates the disparities to ensure maximum

hysteria and hatred the instant the mist enshrouds the store. It’s a

bit much, and, in the case of Brent, who shoots from reasonable to

obstinate when David asks him to take the tentacle attack on faith,

it’s also too convenient – even as it’s gradually revealed that Brent

is a widely respected legal mind bucking for a seat on the Supreme

Court of the United States. With panic spreading throughout the

supermarket, Brent, unwilling to believe that there’s anything out in

the mist, mobilizes the people of color to follow him out into the

murky unknown to prove his hypothesis. It’s not an implausible

scenario, but it all goes down so quickly that it feels like a plot

device.

And it is. But it has to happen this way for Darabont to adequately set up the devastating third act reveals that elevate The Mist

from simple, second-rate Rod Serling-esque parable to potential horror

classic. As soon as Brent and his group exit, Darabont begins brewing

the discontent, which ultimately pits pragmatists versus zealots. The

primary catalyst for this conflict is Mrs. Carmody (Marcia Gay Harden),

an evangelical, fire-and-brimstone Christian who goes from nut to

prophet as the situation grows more desperate. For a while, the more

practical contingent, let by David, begrudgingly coexists with Carmody

and her converts as they plot their own exit strategy; but when she

begins calling for human sacrifice, the grim uncertainty of the mist

starts looking pretty darn inviting.

But how much grimness can

one take? That’s the final question put before David and his

survival-minded group – and it probably isn’t too much of a spoiler to

reveal that the final scene does not take place on a beach in Mexico.

Still, no one familiar with Darabont’s previous work could ever expect

him to deposit his characters in such a maelstrom of despair. The Mist

is an furious movie. Like many films released this fall, it’s brazenly

misanthropic and openly contemptuous of the country’s post-9/11

mindset. But before it arrives at its ghastly terminus, it’s a

thrilling horror film with a corroded conscience: women, children and

the elderly are all game for the dispatchin’. It’s been a while since

horror fans have been treated to a film this thoughtful and expertly

performed (by the entire company, which includes the masterful likes of

Toby Jones, Francis Sternhagen, William Sadler and a particularly

exceptional Jeffrey DeMunn).

It’s just that it’ll be a very long while before you want to watch it again. The Mist provides plenty of punishment to live on.