What’s the difference between a dæmon and a demon? One could spend a good deal of column space and bore a great many readers differentiating between the two, so, for the purposes of this article, we shall define a dæmon as "a person’s attendant spirit" and a demon as "a film by Lamberto Bava".

What’s the difference between a dæmon and a demon? One could spend a good deal of column space and bore a great many readers differentiating between the two, so, for the purposes of this article, we shall define a dæmon as "a person’s attendant spirit" and a demon as "a film by Lamberto Bava".

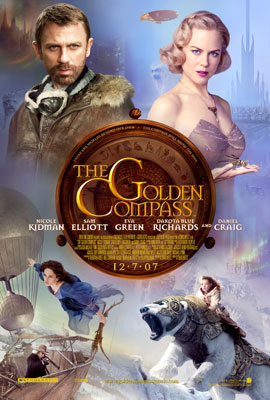

Unfortunately for gorehounds and fans of Go West, the latter has nothing to do with Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, the first chapter of which, The Golden Compass, will thunder its way to the big screen this December under the direction of Chris Weitz. The protagonist of this installment is Lyra Belacqua (played by Dakota Blue Richards), a young orphan who journeys to the arctic to rescue her friend Roger, who has been kidnapped by "The Gobblers". To reach her remote destination, she hitches a ride with the glamorous Mrs. Coulter, who turns out to be responsible for Roger’s disappearance. Coulter is the head of the powerful (and, in the film version, fascist) Magisterium, and she covets Lyra’s "alethiometer", a golden, some might say "compass-looking" device that can answer any question asked by its beholder (though it has a nasty habit of getting stuck on "Ask Again Later"*). To defeat Coulter, and rescue countless other kidnapped children, Lyra will need the help of her adventuresome uncle Lord Asriel (Daniel Craig), the northern witch Serafina Pekkala (Eva Green) and everyone’s favorite cowboy balloonist, Lee Scoresby (Sam Elliott).

Good or evil, one thing all of Pullman’s dramatis personae have in common is a dæmon, which is visually embodied by an animal that reflects each character’s temperament. For example, the bold Lord Asriel is accompanied by a snow leopard named Stelmaria, while the evil Mrs. Coulter struts about with a nasty golden monkey. As for Lyra, her dæmon, Pantalaimon, is undefined; at any given moment, he could be a mouse, a ferret, a wildcat, a sparrow, or Richard Lynch. Basically, dæmons don’t settle until their flesh-and-blood companion fully matures.

On the page, it’s a great idea; on film, it’s an involved visual f/x process that requires the work of around 500 artists rendering somewhere in the neighborhood of 800 shots (600 of which will make the final cut of the movie). To pull off this crucial effect, New Line Cinema turned to Rhythm and Hues, the twenty-year-old visual effects company behind the Oscar-winning talking animals of Babe. The company recently earned a second nomination for its work on The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, and it’s this team that’s been hired to imbue the dæmons with a fluid sense of character that’s rarely seen in CG animals not played by Andy Serkis.

Aside from a couple of trailers, little has been glimpsed of Weitz’s adaptation of The Golden Compass, so New Line’s October 15th unveiling of the still unfinished work of Bill Westenhover (Visual Effects Supervisor), Gary Nolin (Visual Effects Producer), Raymond Chen (Co-Visual Effects Supervisor), Erik de Boer (Animation Director) and Mike Meaker (Art Director) for a large group of print and online journalists had to be taken as a vote of some confidence. They wouldn’t have bussed this seen-it-all group out to Playa Vista, California if their "A" team animators had fucked up royally, right?

Before getting into the nuts-and-bolts of how concept paintings and photos of real animals influenced the development of their daemons, the Rhythm and Hues gang showed off an extended trailer of sorts (scored to Clint Mansell’s haunting "Death is the Road to Awe" cue from The Fountain) that New Line should put online right now if they want to fully convey the narrative scope and thematic ambition of this difficult-to-pin-down fantasy (i.e. for those who haven’t read the books). The kidnapping of Roger may still feel like a big nothing (to be honest, I’m not even sure if it’s addressed in the theatrical trailer), but at least Lyra’s basic predicament – the protection of the alethiometer – is more compelling, while Kidman’s Coulter finally feels like a formidable, hiss-worthy villain.

The effects work, particularly Pan’s erratic transformations (and the dusting "dæmon deaths"), really stand out in this assemblage; there’s a nice little offhanded moment where the dæmon flows from ferret to sparrow to ferret again as he follows Lyra through what appears to be a library. Later on, Pan stares out through a magnifying glass and impishly sticks his tongue out at the viewer; it’s an endearing character gesture that’s undeniably enhanced by the vocal work of Freddie Highmore, but absolutely sold by the Rhythm and Hues gang. What should look distractingly cartoonish comes off as stunningly lifelike.

Worried that "Joe Moviegoer" might not get that these dæmons aren’t just unusually devoted pets, Weitz asked Westenhover and his crew to give these characters a distinguishing, unnatural feature that would hammer their otherness home; after playing with characteristics like mild transparency, they finally settled on giving the dæmons a strange, multicolored play of light on their pelts. In theory, it’s an interesting fix for something I’m not entirely sure needs fixing; in practice, it gives the f/x a jarringly unfinished appearance, and should be muted.

In light of Rhythm and Hues’ past success with polar bears (they were behind those sickeningly cute Coca-Cola spots), it’s a bit odd that they weren’t awarded the opportunity to bring Iorek Byrnison and the other arctic "armored bears" to life. Though Nolin confirmed that they did put in a bid, it went to one of the other nine companies involved in the film’s visual effects artistry. It was hard to tell to what extent the group was miffed by this; Chen in particular seemed quite enamored of their polar bear work for Narnia. That said, they were quick to counter that the designing and animating of the dæmons was more than enough to keep their hundreds of animators (including teams in India and elsewhere in Asia) busy.

When asked to identify the film’s most challenging sequence f/x-wise, the immediate answer was the finale – i.e. the one that will now open the second film provided this first installment makes lots and lots of moolah. After checking with New Line’s publicity team for leeway on details (and receiving a "zip it!" reply), they intimated something about an Aurora Borealis effect before moving on to say how tough it was to animate a monkey giving a cat what for. As I wrote last week, I think they’ve delivered the Odessa Steps of monkey-on-cat violence, so the Oscar is pretty much theirs to lose.

I just hope we get to see this killer cliffhanger soon – and not merely as an extra on The Golden Compass’ DVD. Audiences will decide its fate on December 7, 2007.

*