This review includes major spoilers for the ending of Into the Wild, although they won’t be spoilers for anyone familiar with the story of Christopher McCandless.

This review includes major spoilers for the ending of Into the Wild, although they won’t be spoilers for anyone familiar with the story of Christopher McCandless.

For many people the death of Christopher McCandless is a chance to be condescending, or even worse feel superior as they sit on their asses and take no chances in life. These people will complain that Sean Penn has mythologized Chris in the movie version of Into the Wild, canonizing his own cinematic saint. They aren’t completely wrong – Penn paints McCandless’ years on the road as Alexander Supertramp with a hagiographic brush, doing all but granting the young man a CGI halo as he travels the nation and touches and heals those he meets – but they’re missing the point, which is that Sean Penn wants to mythologize Chris McCandless. He’s making a movie as earnest as its subject, a film that allows itself to be open in all the ways that Chris McCandless only learned to be in his final dying days. Distance and detachment and cynicism are the order of that day, and Penn rejects that, just as he rejects the modern drive to cut every hero off at the ankles. As the lights came up at the end of Into the Wild I don’t know that I knew more about Chris McCandless or the facts and truthful details of his journey than I did after reading John Krakauer’s excellent book, but I felt like I had found some things out about myself and the way I approach the world versus the way I wish I did.

After graduating from Emory College, Christopher McCandless disappeared from his comfortable world and took to the road as a penniless hobo whose ultimate dream was to get up to Alaska, to the wide open untouched spaces and live far from people and society. McCandless, who rechristened himself Alexander Supertramp, didn’t just know Thoreau’s Walden by heart, he had the book imprinted on his soul. He’s the sort of person who is easy to dislike – a well off white kid looking at the romance of poverty from his position of plenty – but the truth is that McCandless had a fiery idealism that transcended the standard trustafarian bullshit that passes for hippie and counterculture these days. McCandless didn’t travel the country following Phish and getting fucked up but rather took the back roads and sought out the places where he could be alone. Even without Penn’s adoring gaze it’s not hard to imagine that four hundred years ago McCandless would have ended up as a holy man in a hermitage.

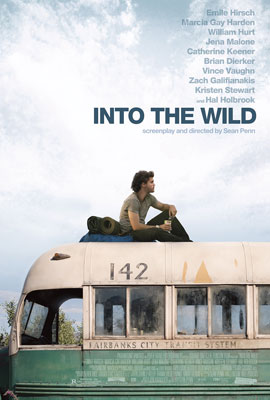

Penn, who wrote as well as directed Into the Wild, structures the film in a deceivingly complex way. He starts with the final months of McCandless’ life, as he finally makes it out to the wilds of Alaska and finds an abandoned bus deep in the woods that had been used as a shelter by another seeker at another time. The film then flashes back to McCandless’ graduation and his final encounter with his family; after sending all his savings to Oxfam, Chris burns his identification and sets out on the road. It’s then that Penn begins the story of the movie, with a title card telling us this is Chapter 1. Everything else was prologue, Chris’ real life begins here. But while it’s Chris’ life, and we occasionally hear him in voice over and read his words written on the screen, large chunks of it are told from the point of view of his sister, who never saw Chris after his graduation. And to add another fold to the narrative, Penn is not afraid to have actor Emil Hirsch break the fourth wall a number of times, some more shocking and overt than others (for me the most breathtaking was during the death scene, as Hirsch/McCandless reaches for the camera that is hovering over his face). This movie is an interpretation of an interpretation, and in the end it isn’t about who McCandless is or what he did but how we see it and interpret it for ourselves. The meaning of the film is how we fold the meaning we get from the film into ourselves as we leave the theater; I wish religious people approached their scriptures in this way.

Penn is completely taken with McCandless as a concept, and he’s completely taken with Hirsch as an actor. It’s not hard to see why – Hirsch’s performance in Into the Wild leaves me at a loss for superlatives. The barrier between the actor and the character feels non-existent, and in a way deeper than the usual Method acting nonsense. Thinking about the film as a series of interpretations meant for your interpretation, it’s hard not to see Hirsch’s performance as his own internalized interpretation of McCandless, where instead of playing another character Hirsch simply opened up those parts of himself where McCandless resonated. Penn is also taken with Hirsch’s physical beauty, and it’s hard not to be, but there’s something refreshingly non-sexual about the way the camera looks at Hirsch, even as it lingers on him in the most personal and private moments. In many ways Penn’s camera views the star with the same steady wonderment as it does the natural scenery in which Chris lived.

One of the advantages of Into the Wild as a movie over Into the Wild as a book is that Penn went to the places where McCandless went, and so the film is filled with stunning vistas and gorgeous details. Penn doesn’t just do landscapes; he also takes the time to observe a caterpillar as it crawls on a branch or a faucet as it slowly drips water in the desert. The film doesn’t have an overtly ecological message – we don’t hear people going on about recycling or have a juxtaposition of suburban sprawl and nature forced on us (the closest the film gets is during McCandless’ brief sojourn in Los Angeles. It’s one of the film’s worst scenes for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that urban decay and decline is directly linked with the only black people to show up in the whole movie. Technically I am sure that the ethnic make-up of these scenes are correct, but there’s something weird about how white McCandless’ journies are. Even his brief sojourn to Mexico is essentially glossed over) – but any modern audience member must realize how precious these sights are, how endangered these places are.

A film as earnest as this will take missteps along the way, and Penn overdoes it more than once, rendering something silly rather than impressive. But it’s that fearlessness – Penn’s not afraid to put himself on the line and get laughed at – that makes me love the film. It’s a fearlessness that McCandless had as well. Penn leans heavily on his own psychological evaluation of Chris, that his parents’ bad marriage and a secret in their past is what led him to be the solitary man on the road, and I think he may overdo it – by the end I felt like the point had been well made and could be let go – but I also like the even handed way that he treats the parents. The film was made with their support, and I think he got it by never forgetting the basic selfishness of what Chris did when he set off on an adventure without ever writing or calling home and by telling their story alongside Chris’. In the end he amps that story to the breaking point by having a dying Chris imagine himself going home to the family – The Last Temptation of Alexander Supertramp, if you will – but again, it’s the way Penn lets it all hang out that makes the film so damn admirable.

What makes it so devastating are the final minutes. Watching McCandless, as lays dying in the bus, finally make peace with the demons inside him that never allowed him to get too close to anyone in his life or his journeys, is heartbreaking. Of course your interpretation will vary: is his breakthrough – ‘Happiness is only real when it’s shared’ – coming too late or just in time? Was McCandless’ whole journey and his constant testing of himself against nature and the world, all in the service of figuring that out? And passing it on to us?

I would never do what Christopher McCandless did, and yet I found Into the Wild to be incredibly inspiring. The point isn’t that you should go off into the woods, and anyone who sees that as the message of the film, or McCandless’ life, are missing it all. The message is that there are alternatives, that the way to happiness doesn’t have to be in a suit and tie or tied to a career or to success. Happiness is in the world around you and the people living in it, and the love you have for them and they have for you. And you don’t have to spend years tramping around America to learn who you are; following Christopher McCandless’ footsteps doesn’t mean hiking to that bus in the middle of nowhere but facing the challenges ahead of you on your own terms, deciding your own path. Define your life, don’t allow it to be defined for you.