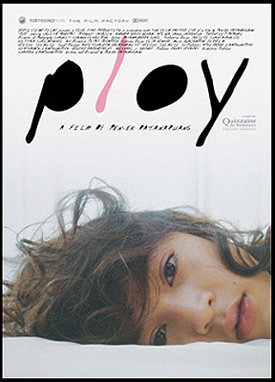

In the last four years, the work of Thai filmmaker Pen-ek Ratanaruang has grown more alienated and interior. The trend began with his career-high Last Life In The Universe, which built a love story in spite of language and cultural barriers. The follow-up and companion piece of sorts, Invisible Waves, tore the love story apart but kept the barriers. Now Ploy crushes a broken collection of spouses and fantasy partners into a hotel room and calmly observes as the people implode.

In the last four years, the work of Thai filmmaker Pen-ek Ratanaruang has grown more alienated and interior. The trend began with his career-high Last Life In The Universe, which built a love story in spite of language and cultural barriers. The follow-up and companion piece of sorts, Invisible Waves, tore the love story apart but kept the barriers. Now Ploy crushes a broken collection of spouses and fantasy partners into a hotel room and calmly observes as the people implode.

Ploy is Ratanaruang’s version of Eyes Wide Shut. It’s a hushed nightmare of marital tension and perceived infidelity played out through ambiguous dreams amid partitioned spaces that reflect the couple’s sequestered desires.

Former actress Dang (Lalita Panyopas) has been out of Thailand for years; she’d gone to the states, where she married the restauranteur Wit (Porn-wut Sarasin). The couple has returned to Bangkok for a funeral, checking into a posh hotel. There’s a chilly distance between them; they share the casual intimacy of familiar partners, but they seem unable to communicate directly.

Wit escapes to the bar downstairs, where he meets Ploy. Apinya Sakuljaroensuk, withdrawn and so obviously underage with her exploding afro and lanky boy’s body, is an unlikely romantic interest but obvious antidote to Dang’s personality. She smokes and listens to music with her boyfriends, but Wit gets her to hang around by tossing out conversational softballs. She’s got to spend the night waiting for her mother’s train to arrive in the morning, so Wit invites her upstairs.

You don’t need me to tell you that Dang resents Ploy like an unexpected outbreak of the clap, but the girl’s place in the room is ambiguous. Does Wit harbor any real sexual desires, or is he just bringing a moppet-shaped wedge into his marriage? Fantasies and uncertain periods of sleeplessness and insomnia vie for time as the night passes; Ratanaruang captures exactly that feel when you’re tense and exhausted but awake waiting for that word or movement that signifies anything.

Meanwhile, a real tryst is developing in the hotel. The bartender (Ananda Everingham) ends his shift and moves upstairs to where an attractive maid (Phornthip Pananai) is preparing a room. In disconnected scenes slowly doled out, the couple engages in a variety of sexual acts.

We start to wonder, who is real? Who is dreaming whom? Scene transitions are often triggered as one character wakes or comes back to consciousness. Eventually Ratanaruang puts it all on the table when Ploy describes her dream of the maid and bartender, but that doesn’t make their encounter any less real, or several of Ploy’s realities any more convincing.

The timelines of dream start to tangle. Is Dang dreaming Ploy, who is dreaming the bartender and maid? But is the maid dreaming Wit and his wife? There’s a moment of terrific tension, a tipping point where you wonder if the story might break open like a watch, springs of dream flying everywhere and wrapping each other into knots.

Instead, it takes a soft nose dive.

Refusing to ride the crest and fall of the tense interplay between Ploy, Wit and Dang, Ratanaruang lobs a final long, maybe-dream sequence. Dang skips out of the room, meets a man downstairs, and is quickly mired in a situation that’s dangerously close to boilerplate torture porn plotting. Well-acted and tonally similar to the rest of the film, this final act is probably enough to make some audiences afraid, but I felt like it’s for all the wrong reasons. The interesting tension drains away quickly.

In place of the unease and uncertainty that characterizes the film’s balance, I was left with questions that became academic and merely calculated: Oh, another dream. Or is this real? To what extent? The end result is an unstable ending that suggests things are more right than wrong, that Wit and Dang’s chilled, distant night taught them the proper lesson.

I’m fond of Ploy in the same way I am of the rather aimless and contrived Invisible Waves. It has such a specific and well-crafted atmosphere of oppression that I can’t help but be pulled in. The photography and minimal sound design are hypnotizing, and despite a protracted pace I was in some way sitting on edge waiting for something to break. But the final narrative turn acted like a door slamming shut, and Ploy locked me out as it blithely turned into a film that embraced convention with open arms and an empty head.