Tony Gilroy’s directorial debut, Michael Clayton, blares its brilliance over the opening credits, as Arthur Edens (Tom Wilkinson), the manic depressive ace litigator for Kenner, Bach & Ledeen (a corporate law armada blasting away in defense of a massive agrochemical conglomeration called U/North), rails in high Chayefskian dudgeon against the malevolence of corporate America, and, in particular, the baleful actions of the aforementioned company which he’s about to guide into a favorable settlement. As unhinged harangues go, it should be a corker. There’s just one problem: it’s delivered offscreen, bereft of context.

Tony Gilroy’s directorial debut, Michael Clayton, blares its brilliance over the opening credits, as Arthur Edens (Tom Wilkinson), the manic depressive ace litigator for Kenner, Bach & Ledeen (a corporate law armada blasting away in defense of a massive agrochemical conglomeration called U/North), rails in high Chayefskian dudgeon against the malevolence of corporate America, and, in particular, the baleful actions of the aforementioned company which he’s about to guide into a favorable settlement. As unhinged harangues go, it should be a corker. There’s just one problem: it’s delivered offscreen, bereft of context.

This is the very smart Tony Gilroy trying to be way too clever as a screenwriter, and it’s just the beginning of the film’s unceasing attempts to come at the 1970s paranoid thriller and the 1980s legal melodrama sideways. He loves to enter scenes late or get out of them early, and, of course, he plays with chronology as a means of masking convention. The effort is appreciated; at its best, Michael Clayton recalls the eerie obliqueness of Pakula and the otherworldly tough guy patois of Mamet. The latter quality is nothing new. As amply demonstrated in The Devil’s Advocate and the Bourne series, Gilroy is a skillful composer of white collar trash talk (Sydney Pollack’s Absence of Malice comes to mind at times); he gets off on the music of seven-figure salary swagger. But his eye for menace when prowling the beige, banal trappings of law offices and airport hotels… this is a gift worth cultivating.

Unfortunately, this sensibility grinds against the film’s rampaging idealism. Despite the unrelentingly dour tone, Gilroy’s endgame is uplift; he wants the world restored to a near utopian state, where justice prevails, the bad guys are shamed (in the most Hollywood fashion imaginable), and the troubled conscience of a corporate bagman is assuaged. Essentially, he wants Jessup to admit he ordered the "Code Red". Pakula would’ve never stooped to this (at least not as a director), while Chayefsky would’ve laced the happy outcome with a heavy dose of arsenic. Pollack, on the other hand, might’ve relented; it just would’ve taken him 140 minutes to get there.

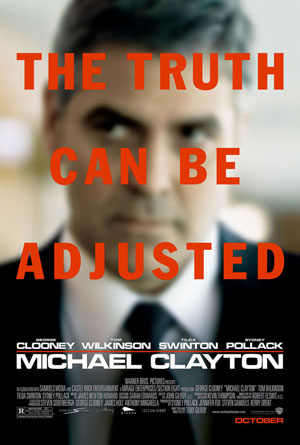

Up until this woefully incongruous, stand-up-and-cheer finale, Michael Clayton is already mightily confused. As a portrait of a professional fixer who’s broken everything in his personal life, it elicits some sympathy. This is due to a masterfully nuanced performance by George Clooney, who, over the last few years, has been subverting his natural movie star charm in one bloodless film after another. (And it’s kind of an outrage. He’s going all Jimmy Stewart ala Vertigo and The Naked Spur, but he’s doing it in emotionally remote exercises like Syriana and The Good German. These aren’t terrible films per se, but there’s not much to savor in them either.) Another, more conventional film (the kind Gilroy’s film wishes it didn’t want to be) would’ve given the audience a taste of Clayton in his prime, rather than introduce him as a miracle worker who’s fresh out of pixie dust. Instead, he’s mired in debt from the beginning (thanks to a failed restaurant venture), failing to connect as a father (to his precocious son), and futilely clamoring for a shot at actual litigation (instead of Winston Wolf-ing his life away). Clayton’s a middle-aged man yearning for a second youth; he’s looking for a reset button even though he’s way too smart and unsentimental to believe such a thing exists.

Desperation has a way of inducing selective stupidity even in the very intelligent, so there’s nothing terribly objectionable about Clayton intermittently reverting to a childlike state. It’s even endearing. The problem is it can’t be rewarded. Given the nature of his job, a guy like Clayton has done his fair share of dirt in his time; pouring cement into the abyss isn’t enough. And failing Arthur as a friend hardly qualifies as a soul-crushing defeat.

Yet Gilroy loves the character too much to deny him complete vindication, and it’s an impulse that’s completely inorganic for this kind of film. In other words, to pull off the big, redemptive resolution, Gilroy has to employ an insultingly implausible twist late in the third act that completely bankrupts the payoff. That some critics and audiences are swallowing this bit of happenstance – depicted in the opening ten minutes, and then re-staged as a rote suspense sequence even though the viewer knows precisely what’s going to happen – is a testament to Gilroy’s facility as a studio screenwriter. He’s adroit at sugarcoating bullshit. But it’s impossible to accept if the film is going to work as an intelligent thriller. Luckily, the film hasn’t been working all that well as anything up to that point, so the offense isn’t egregious. It’s just emblematic of all that ails this thoughtful, but fundamentally conflicted picture.