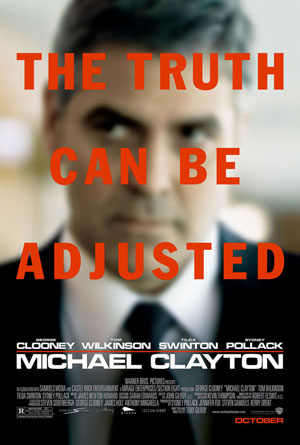

I’d originally thought that Michael Clayton was going to be one of those movies that critics and audiences split on. It’s got a great big payoff of the sort that an adult audience just loves, but it’s also got a couple of weaknesses I’d figured would keep writers (as seen in Devin’s review) from buying into the story of a morally compromised corporate bag man.

I’d originally thought that Michael Clayton was going to be one of those movies that critics and audiences split on. It’s got a great big payoff of the sort that an adult audience just loves, but it’s also got a couple of weaknesses I’d figured would keep writers (as seen in Devin’s review) from buying into the story of a morally compromised corporate bag man.

But looking at the reviews, I’m surprised to see that Devin’s take is among the most dire. Maybe it’s Sydney Pollack’s calm acceptance of evil that sells everyone; that was certainly the quality that hit me with the most force.

Tony Gilroy obviously believes in the film, not just as a mature thriller, but as an antidote to the movies that, ironically, have made his career so far. It’s refreshing to hear an established writer like Gilroy — as a regular script doctor, arguably a sort of Hollywood bag man himself, a notion I’m so irritated to have only considered as I’m posting this interview — talk about working in direct opposition to the sort of movies "he’s been trained to write".

A few words about the conversation at the end, where we’re discussing IMDB. Tony Gilroy worked very briefly on the script for State of Play, but he’s not the writer, despite what you’ll see on the IMDB. (Click here for a screenshot of the film’s current listing.) News about his involvement had flown around based in part on that listing, and he’s pretty pissed off about it, since it’s not his project at all.

For a movie like this, do you start with this character, the bagman, or do you start with corporate culpability and responsibility?

Definitely the character. Though I really had the environment first. I went to all these law firms on Devil’s Advocate, with Taylor [Hackford], and I thought ‘this is just not what we see in the movies’. They all have a wood-paneled room like this [Four Seasons board room] but no one ever goes in there, it’s like there are plastic slipcovers on the sofa. Most lawyers don’t go to court, and they don’t go in that room. There’s this huge, industrial ugly aspect of it. You go to a law firm at 3am and there’s half a dozen people buried under paper on every floor, grinding away like crazy. Nobody looks that great, no one is really pretty. So that environment was first, and then the character came after that. The hard part was reining it in, because there were so many ways the character could go. I almost thought we should do it as a television series, there were so many things for him to fix. So ‘the big issue’ was never the starting point. I don’t see it as an issue movie.

Do think audiences will?

I think it’s an easy, stupid way to look at it. In Europe, and also I think in Canada, there’s a real need and appetite….I think America has so confused the rest of the world that they’re…anything that has some cultural truth about America they’re desperate to put it in a context. "Are you telling us what America is really like?!?" So for that audience, it might be the hook. But I think it’s an easy way out. What passes as the sorta traditional corporate malfeasance, I give that away. I tell you what they did and to whom. I’m not dangling that or making any suspense out of that. It’s not where my interest lies in the movie.

So it is a thriller, but it’s a parallel thriller. And I’ve written several of these movies and ‘fixed’ so many movies like this that I wanted something that had the muscle of those kinda movies, but I wanted to get something else…this movie has what comes before the person makes a crucial decision, and also the aftermath. I wanted those moments that are usually left out of the movies that I’m trained to write. I wanted to come in earlier or catch something that happens later. And really examine the character consequences of living inside a thriller like this.

So that’s where the last shot of the film comes from, where you linger on Michael Clayton. What’s going through his head at that point?

There are a couple different answers to that. That ending does a couple different things for me. One is that I want to recalibrate the vibe of the movie. There’s a big cathartic thing before that which is really satisfying in a big, big way. It’s the payoff for investing in the movie. That payoff is satisfying, but I want to make sure that I reset the vibe before you leave, and if nothing else I’m hoping that people will think about what’s going to happen in the next hours and weeks based on things that take place in the movie. I’m not putting a crawl up and telling people what happened, but this is my way of sorta doing that. I want you to think about the price he paid to do what he did.

I can tell you what George was thinking. I was sitting in a lead police car, George was in the cab behind us and we didn’t really have permission to do what we were doing, so a bunch of cops were helping us out. We had to do it a bunch of times, we were running lights and cars got stalled, and I’m watching him on the monitor the whole time. When we had to reload the camera at one point I went back to talk to him — he couldn’t get out of the cab because there were always a hundred people on the streets around us — and asked him what he was doing. He said ‘I’m just running the movie back in my head.’ So that’s my idea of directing. I go back and ask the actor what they’re doing! That’s how I roll.

So you just let Tilda Swinton do her own thing as well? She looks perfectly like she’s trying to talk herself into confidence.

Yeah! I think a lot of people are doing that. Work makes huge demands on people to front things. A lot of people, most people, maybe everybody, is pretending to be a grown up, pretending to do their job.

She’s almost pretending to be herself. I said to her, imagine as if you’re a rather accomplished classical pianist. You’ve learned the five easy pieces and the whole thing, you know music and can read music…and now you have to go play with Ornette Colman. It’s still music. But you have no idea what you’re doing.

The idea of someone who’s swamped by things coming too quickly and automatically weakened by the fact that she’s pretending to be a good soldier and trying so hard to do the right thing for her company, I thought that was a really good way to dig deep into that, if you could get the right actor. And I did. So to have the villain be really fucked up, to have them be a victim in a away. And that’s another thing that, having written so many villains, you never get a chance to do. You never have a moment where the villain is in doubt. He’s usually got a great explanation, and you have to give him a worldview at the end where he explains why he’s been doing things. But you never catch the moment where he’s looking in the mirror wondering if he should do this. And he never has a boss! So this was a palette cleanser.

So how do you get this movie made with these characters?

After, what, after…pick the number…25 million? 30? What’s the number after which you have to have bad guys wear black hats and complexity disappears? You’re in a test screening, the studio’s paid 100 million dollars to make the movie, their mandate is, everybody needs to understand everything. You have to hit on all quadrants. Everybody has to be clear. "They missed her putting her glasses down! Six per cent of the audience didn’t see that! Reshoot!" So it’s a dollar amount. I wouldn’t greenlight this movie at a high dollar amount. The only way this movie was going to get made was if a star came in and waived their fee. I knew that when I wrote it. Hell, I wrote it with that in mind.

How’d you get George Clooney to do that?

I wrote it for Castle Rock, but by the time I delivered they weren’t a studio anymore, they were a producer. And it was a bad time for them to do it. Sydney Pollack read it and wanted to direct it. I didn’t want to let it go, so he offered to help get it made. We went around for a while, toyed with the script, and I was working with Soderbergh. He read it and said ‘George has gotta do this! We’ll do it with…we’ll do it with pencils and papers! We’ll do it for eighty-five cents! WE’LL DO IT TOMORROW! In my back yard!" He sent it to George and I heard back right away. He said he might even want to direct it, but he had no intention of working with a first time director. He wanted to meet me, and that took two years. In the end there was this whole new renewed push; Steve Samuels in Boston was going to give me the money to make the movie and we started hammering on George to get the meeting, and it worked out.

I’m curious about Bourne. To what degree was the third film scripted hard and fast? Or, to what degree did Paul Greengrass adhere to what you sent?

[There’s a long pause]

I’m only going to say this. One and two were scripted fully before Paul was involved, obviously. For the third, I turned in my draft a week before I went into pre-production on this. I was off after that. That was my economic…it was the only way I could afford to do this movie. It was my version of what George does with other movies. Ultimatum paid for me to take eighteen months off to do this.

Do you feel like the movie is close to the script you tuned in?

I haven’t seen it yet.

What’s the story on State of Play?

I’m raising a diatribe here against the IMDB. You tell me if you agree. I’m really pissed at IMDB. I think it’s totally inappropriate that they put in credits that haven’t been verified. They’ve turned into a utility. They need to tighten their shit up and have a responsible protocol. Or someone should compete with them — I don’t know if anyone could compete with them at this point.

It’s beyond fact-checking. They need a new system. I’ve had it happen to me the other way; if I was Matt Carnahan…I had my brother call Joe and tell him I didn’t put that in there. I’ve had it happen to me, you’re working on something and all the sudden you see [this other credit] and go what the fuck is this? This guy came in for one week and got fired, and he’s on this list behind me? They would never do that to an actor. I think it’s totally inappropriate that [my name] is on there. I worked with Kevin McDonald this spring, there’s another writer on it now, I don’t know what to tell you. It shouldn’t be on there. The problem is they don’t have any competition.

And there’s no standard held up to the site.

You see things on there all the time…how does it get so easy to put things on there, when it’s so hard, even if you’re using a studio and a publicist, to get things off? I don’t want to get on their bad side, but this is fucked. I was really irritated when that came up there. If I put everything…there’s writers on there that have all these credits for movies they worked on that they didn’t get credit on, fuck you! If I did that, sure, I could run my shit down the page. I think it’s really appalling.

Will you direct again?

I’m trying really aggressively. I’m trying to get a movie off before the strike, and I think I’m really close.

Is the strike going to happen?

I think the writer’s end of it is really strong. I think all the stars are in alignment. What is sure is that if you can’t finish shooting a movie by June 30 you can’t make a movie in 2008. All the money will be gone by that point. It’s having a de facto effect, no matter what happens. There’s I think three actors that haven’t filled their slots for the year. It’s never been so organized, I’ve never seen Hollywood so organized in the 20 years I’ve been out there.

So is the atmosphere and situation counter productive, or not?

I don’t know! It’ll be really interesting. There’s probably some movies that wouldn’t have gotten made that will get to go because of it. Good and bad. There’s definitely bad movies that are going to get made, but that’s one thing you can always count on for sure. But maybe a couple really cool things will sneak though just because someone jumped and said yes. And there’s a lot of writing work out there for guys like me right now. For rewriting work, the next six months is going to be a gold mine. People are all going to be busy, pages won’t be ready, actors will be freaking out. So IMDB can really get things complicated in the next three months.