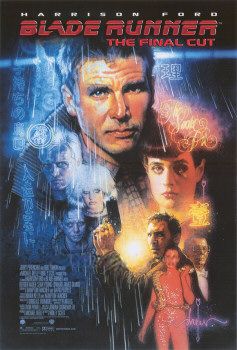

The new version of Blade Runner hitting Los Angeles and New York this weekend, known as Blade Runner: The Final Cut, is a marvel of technology and craftsmanship. The bar has been raised for the sort of wholesale restoration done here; not only is the picture immaculately detailed and crisp, the movie includes new special effects seamlessly and unobtrusively inserted into the action, as well as reshoots done two decades after the fact that will be noticed only by the most exacting viewer. I was looking for some of these reshoots, knowing what scenes were redone, and I couldn’t always find them. A standing ovation has to be delivered to the men and women behind the scenes of this Final Cut, for they’ve turned out a masterpiece.

The new version of Blade Runner hitting Los Angeles and New York this weekend, known as Blade Runner: The Final Cut, is a marvel of technology and craftsmanship. The bar has been raised for the sort of wholesale restoration done here; not only is the picture immaculately detailed and crisp, the movie includes new special effects seamlessly and unobtrusively inserted into the action, as well as reshoots done two decades after the fact that will be noticed only by the most exacting viewer. I was looking for some of these reshoots, knowing what scenes were redone, and I couldn’t always find them. A standing ovation has to be delivered to the men and women behind the scenes of this Final Cut, for they’ve turned out a masterpiece.

The strange thing about watching this cut of Blade Runner, and being awed by the work done to bring it to this state, is that I think I liked the film less than ever this time around. I’ve never liked Blade Runner, an opinion I mostly kept to myself when I was younger. I thought the ‘Director’s Cut’ would fix my problems with the film, but every issue I had with the movie seemed magnified. The Final Cut doesn’t change any of my issues, although a tightened pacing makes the film less painful to sit through in its entirety.

The problem with Blade Runner is that it’s design porn first and a movie a distant third or fourth. I have pondered the idea that it’s ironic that a film about androids should have absolutely no heart, but I think that’s giving Ridley Scott way too much credit here, since his final vision of the film includes the ridiculous and unsupportable idea that Deckard is a replicant. The ending of the Final Cut (like the ending of the Director’s Cut) hints that Scott is one of those filmmakers who just doesn’t understand his own movie.

Right from the start I have trouble connecting with Blade Runner. What’s the point of making an artificial lifeform where the only way you can tell they’re artificial is to ask them stupid questions? Shouldn’t someone in the design process thought to insert a chip or a barcode or… I don’t know, a serial number on their component parts like the film shows they do with artificial animals?

Of course if the replicants were easy to find there’d be no need for Blade Runners, the specialized police who hunt them down ever since they were outlawed on Earth. Watching Harrison Ford of 25 years ago deliver a great performance as the dissolute former Blade Runner pulled in for Just One Last Job only serves to remind you that this guy has been text messaging it in for years now (I would define text messaging it in as less effort than phoning, and definitely with poorer spelling); Deckard wearily moves through the film but with a grace that can only come from an actor as charming as Ford was in the day. The film places other fine to great actors around him, and they all deliver fine performances, but each part feels like a cog in a clockwork mechanism as opposed to an organic piece of a story. Looking around JF Sebastien’s house of genetically engineered toys I couldn’t help but feel the setting was a microcosm of the movie itself – pleasantly designed, intriguing, strange and utterly without life.

There’s no denying that once the film picks up in the third act, with Deckard taking on the rogue replicants who have returned to Earth on an existential mission; Scott can direct movies, there’s no question there. It’s just that I don’t feel he knows how to invest emotion in them. The only Scott film that has ever made me feel anything other than technical admiration was Alien, and that made me feel terrified – not an easy feat, but not quite a transcendent emotion. There’s a love story in Blade Runner, or at least there is a perfunctory meeting of two people. There’s a philosophical debate at the heart of Blade Runner, but it feels like someone writing Camus in diamonds – it sure looks pretty, but the meaning gets lost.

Although it’s perhaps worth noting that this version of Blade Runner, which I saw projected in an awesome digital format, may have even killed my ability to enjoy the film’s crowning achievements in design. Like the characters, nothing here feels organic – and I say that knowing this is an inorganic future. I mean organic in a deeper sense of the vision; while some aspects – the multicultural stew of Los Angeles – feels thought out, too much of the movie’s design feels like it’s there to be cool. Look at Deckard’s apartment, which is apparently decorated in late period Nostromo – why would anyone want that design covering every square inch of their home, even the cabinets? It’s got cool texture, but when you look at Deckard’s apartment as a place where a man lives, it makes no sense except as some kind of visual and maybe thematic wink. That’s the danger of a film too well designed – the art direction starts to move away from implying or suggesting themes or moods and just flat out stating them.

The crystal example of this is the death of Roy Batty – a moment so over the top and overwrought that even in my most angsty teenage years I couldn’t embrace it. His speech is nonsense, all pretty word sci-fi signifiers that mean absolutely nothing whatsoever (the Tannhauser gate? You’re just stringing syllables together here) , until he gets to the cloying finale: "All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain." Like, because he’s crying… and it’s raining! I heard a similar sentiment once expressed on an episode of Mork & Mindy where an upset Mindy took a walk in the rain because no one could see her crying. There’s about the same level of profundity at play here, except that Batty releases a dove that he got from who the fuck knows where. I hope to have the foresight to be so symbolic at the time of my passing. By the way, the new edition fixes a major problem here: the dove used to fly off into an incongruously blue sky; now it’s taking flight into the rainy cityscape of future Los Angeles. A major improvement.

Any thematic elements that the film had been cultivating – and I do think there are interesting philosophical concepts buried here in this New Wave melange, if they are not ever dealt with with full coherence – get shunted at the end of the movie when it’s so heavily hinted that Deckard is himself a replicant. It’s sort of fitting that Scott shoe-horns this in, as it’s a part of his lack of interest in deeper meaning and narrative in favor of coolness. There’s no way that Deckard can be a replicant, and the movie almost goes out of its way to prove that. The most obvious piece of evidence is that his history as a Blade Runner is not just remembered by him but by other characters – short of M Emmet Walsh being a replicant or weirdly in on Deckard being a replicant, how could the two have worked together in the past, which they certainly did? The argument essentially has to end there, because to claim that Walsh’s character was in on it is stretching any reality at all and taking things that the text never delivers. You could go on, though: why doesn’t Deckard have super strength like the other replicants who keep beating the shit out of him? And why would you make a replicant who has a gun and a license to shoot whoever he feels like shooting, since the only way to tell who is an who isn’t a replicant is by asking them dumb questions, which will be too late once they’re dead? This seems like a recipe for disaster, but then again the folks at the Tyrell Corporation don’t seem to have thought out their replicant strategy very much at all.

Projected in digital format with booming, all-encompassing sound, Blade Runner: The Final Cut is a marvel of technology and dedication. As a film it’s still the same dead-eyed pretty girl who looks good on your arm but is a real bore over dinner.

The Movie: 6 out of 10