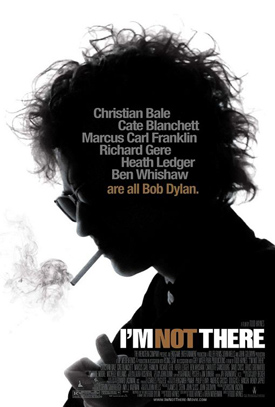

Few things at Toronto this year made me happier than the fact that I’m Not There, Todd Haynes’ much-questioned ‘biography’ of Bob Dylan, was good. Scratch that. Albeit uneven, the film glows with outrageously great moments, many featuring Cate Blanchett’s androgynous transformation. This is a wickedly smart and lively flick that sidesteps biopic clichés (like the ones I mentioned here) and engages the complexities of a shifting public persona rather than trying to smooth them out into a single character reduction.

Few things at Toronto this year made me happier than the fact that I’m Not There, Todd Haynes’ much-questioned ‘biography’ of Bob Dylan, was good. Scratch that. Albeit uneven, the film glows with outrageously great moments, many featuring Cate Blanchett’s androgynous transformation. This is a wickedly smart and lively flick that sidesteps biopic clichés (like the ones I mentioned here) and engages the complexities of a shifting public persona rather than trying to smooth them out into a single character reduction.

The biopic frequently engages the question Brad Pitt asks in The Assassination of Jesse James, "do you want to be like me, or do you want to be me?" So many fall uneasily into the gutter in the middle of that query. Of course Jamie Foxx wants to be like Ray Charles, and his performance is meant to convince us how beautiful it would be to be Ray onstage despite all his failings. But there’s little insight there, and rare art beyond what it takes to replicate an artist’s performances. Watching a million-dollar parrot is neat, sure, but I’ve got YouTube for the real thing.

Musical bios can be grimy, but most remain idol worship masquerading as truth. Not a terrible sin, really, since that’s the entire point of pop stardom. That is, unless you’re Bob Dylan, famously rebellious against the trappings of pop music and popular culture.

Because Dylan is a noted contrarian, Haynes is as ideal a chronicler as were D.A. Pennebaker and Martin Scorsese. Whether watching the failure of Velvet Goldmine or the success of I’m Not There, you never get the sense that Haynes wants to be the people he’s chronicling. He is very openly the devoted fan, but one distinguished by an alchemy that turns fandom into inspiration and eventually art.

As he’s obviously intrigued by David Bowie, Haynes unsurprisingly gloms onto the idea of Dylan and his shifting identities. The fantasy/reality chiaroscuro that hurt Velvet Goldmine here is more balanced, with Haynes exploring shards of personality both ‘real’ and invented, but avoiding too-broad fantasy.

It’s useful to know who plays whom:

Ben Whishaw is Arthur

The poet Dylan of Don’t Look Back, speaking half-candidly about himself, his image and career, essentially narrating and unifying the film.

Marcus Carl Franklin is Woody Guthrie

The young Dylan fancying himself a rail-riding hobo, carrying on in the tradition of work songs and gospel blues, self-consciously calling himself after his musical hero.

Christian Bale is Jack

Dylan’s first famous incarnation, the inspiration for the early ’60s folk scene and counterculture protest figurehead.

Cate Blanchett is Jude

The ‘electric Dylan’, beginning with his incendiary and alienating performance at the Newport Folk Festival. Cate’s walk-on and first interaction with the audience is absolutely fucking perfect. If anything goes down in history as an indelible image from this movie, it’s right here.

Heath Ledger is Bob Dylan

In some ways the most fanciful of Haynes’ constructions, Ledger is an actor with no seeming relation to Dylan, but his career, fame and romantic entanglements all mirror Dylan’s own.

Richard Gere is Billy The Kid

Dylan, desiring to retreat from the press and limelight, fancying himself as a reclusive outlaw.

Haynes wears his heart on his sleeve. Blanchett’s Dylan catches his eye more than any other. For example, the folky populist played by Bale gets short shrift. Haynes seems to have little use for that incarnation except as a foundation for what came later. Bale, for his part, submerges himself in the role, projecting a surprising physical and vocal likeness.

You’d have to be blind and deaf not to fall in love with Cate Blanchett’s performance. This isn’t her Katherine Hepburn, or even Elizabeth. On the first viewing you’ll probably never stop being aware of the fact that, yep, that’sa woman playing Dylan. Yet that top-level awareness took nothing at all away from the fact that she works, in every possible sense. Of all the actors assembled for the film, she has by far the most vitality.

Haynes effectively rewards her performance with the juiciest material in the script. Her jousts with a serious BBC journalist (Bruce Greenwood, projecting academic concern) are some of Dylan’s most famous public moments. Blachett blows the doors off every set, whether she’s meeting Allen Ginsberg while riding in a cab or dripping derision introducing Brian Jones as a member of ‘that famous cover band’.

Every other actor is finally subsumed into Blanchett’s Dylan, and you can very easily imagine Haynes fashioning a cut that features no one but her. Ledger convinces as the fantasized victim of fame, as does Marcus Carl Frankin playing the idealistic young singer learning how to express himself. But it’s Blanchett you’ll want more of, and Blanchett that you’ll enthuse about to friends afterward, just like I’m doing now.

Oddly, the film also lingers on Billy the Kid. Cutting this vision of Dylan by half would help the film immeasurably. Not that Gere lacks gravitas or character as Billy; his subdued eyes and quietly coiled energy are ideal for the character. And the segment has purpose; specifically it provides a great window into Haynes’ image of the singer when Pat Garrett turns up, appropriately cast. (I shouldn’t give away who plays Garrett, as he brings the point of the segment home.)

Haynes keeps the film light whenever possible. The monumentally reliable Julienne Moore turns up as the story’s version of Joan Baez, and Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon has an amusing scene as another folk singer. Drawing a line back to Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy The Kid, Kris Kristofferson provides some offscreen narration, while the lone appearance of The Beatles is in a puff of smoke reminiscent of their earliest filmed promos. Even David Cross is more fun than distracting as Allen Ginsberg, a feat I wouldn’t have thought possible.

The obvious question is whether I’m Not There has more to offer dedicated fans or Dylan neophytes. Fans are probably going to be angry; there is, after all, a lot of license taken here. But on a second viewing (well-deserved, I’d say) those same people will probably take away the richest rewards. I fall into the neophyte category, so obviously I’m able to speak to that contingent; I was aware that layers of history were being overlapped and rearranged at will, and I quickly stopped trying to figure out how the film was supposed to mesh with reality — in the end, that’s not the point.