I get no small amount of amusement from the fact that the latest films from Bela Tarr and the Coen Brothers share the same plot. It’s a tribute to the infinite variability of storytelling and cinema that, despite a common narrative spine, the films couldn’t be more different. Looking at No Country For Old Men side by side with The Man From London is like examining a pair of conjoined twins where one is human and the other a tree sloth.

I get no small amount of amusement from the fact that the latest films from Bela Tarr and the Coen Brothers share the same plot. It’s a tribute to the infinite variability of storytelling and cinema that, despite a common narrative spine, the films couldn’t be more different. Looking at No Country For Old Men side by side with The Man From London is like examining a pair of conjoined twins where one is human and the other a tree sloth.

Tarr is a master of black and white composition, and an ethusiast of takes which stretch attention spans past the breaking point and into a realm of pure perception. Here he applies his distinctly European skills to a story that seems very American.

Near a moored ship two men argue over a satchel, leaving one dead and the satchel seemingly lost to dark waters. A third man fishes out the satchel, which is full of money, and then must evade those who arrive in search of the cash.

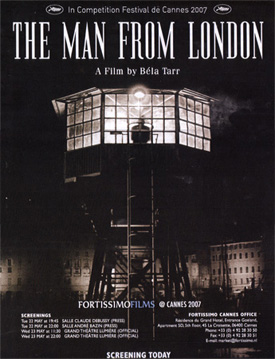

Maolin (Miroslav Krobot) is a railyard worker with an office standing on metal stilts above the rail’s origin point at the docks of a French port. His life is as colorless as the film’s stock. A shrewish wife (Tilda Swinton, speaking English but dubbed in Hungarian) presides over his home, and his daughter works as a shopgirl for a woman who uses the girl’s youthful sex appeal to bring in customers. Maolin is wearied and humbled by his life and station. Any way out is a chance worth taking.

The film opens with Maolin ensconced in his office like a spider at the center of a dark web. In a tracking shot that lasts a full reel, we see through his eyes as passengers disembark a ship from London. Panning slowly back and forth, we observe a conversation on the deck, a satchel tossed ashore, passengers making their unsuspecting way to a train, and finally the violent argument that leaves one man dead, another on the run and a bag of money floating in the water.

The technical virtuosity of this shot is stunning, though not in any way a grab for attention. Camera movement and action are impeccably timed, actors moving through the ship and across the docks in synchronization with the camera’s pan. The film is cold and beautiful from beginning to end, but this single take, which is mirrored at the film’s conclusion, is a marvelous construction.

We learn soon enough that Tarr is providing a more subjective view of reality than we first assume. Maolin’s office may seem dark and secure, but seen from outside it’s actually brightly lit and terribly vulnerable. High above the port, there’s no question who might have seen the original quarrel and found the satchel. That understanding makes Maolin look even more pathetic than he otherwise might; he’s a mere voyeur, not a commander.

Soon there are multiple parties looking for the money, and Maolin is at a vague crossroads. I say vague because he seems to have little idea what to do with either money or fear. While Llewellyn Moss, hero of No Country For Old Men, first evades then faces the man chasing him, Maolin acts less impulsively but more recklessly, costing his daughter her job (and social standing, according to his wife) and buying her grand, inappropriate gifts.

A lifetime of immobility and indecision has primed this man to do absolutely nothing when suddenly faced with the option to change everything. Tarr plays the stasis out in unnaturally long shots. Is there a separate word for a protagonist who takes almost no action? Regardless, Tarr’s camera eye reflects Maolin’s beaten down turmoil, watching characters eat or walk up a street or simply exist, each carving out a tiny, invisible corner of the world. The sense that he doesn’t even have that refuge is crushing, and pushes him further into the path of the wrong men.

But while two men — one of the two initially struggling over the satchel and a detective from London — are looking for the money, Maolin never even moves. Instead he waits, almost knowing that his windfall is temporary. In the end, there’s finally a sort of action, one that’s destructive and horrifying, but possibly better than nothing.

Every frame of film drips ‘old world’. There’s not a happy or comfortable face in these cans of film. All dour eyes and grey skin. The movie might actually be in color. It would be the same either way: Film gris. Tarr’s basilisk technique can be sublimely eloquent when applied to such a landscape, but it also closes the story down to all but a few emotions. Permutations of misery and uncertainty boil under the stone surface of The Man From London, making it a too-clear mirror of dark, hidden corners.

7.1 out of 10