"I make my films like you’re going to *die* if you miss the next minute."

"I make my films like you’re going to *die* if you miss the next minute."

If there’s a finer encapsulation of the experience of watching an Oliver Stone film, I haven’t heard it. Love him or hate him (and no major American director has fewer in-betweens than perhaps Spike Lee), there is no denying the intensity of the man’s cinema. After making his name as one of the top screenwriters in Hollywood during the late 70s and early 80s with Midnight Express (for which he won an Oscar), Conan the Barbarian and Scarface, Oliver Stone transitioned to directing with The Hand. This led to a four-year, quite involuntary layoff, after which he returned to the director’s chair with the independently produced Salvador, a success d’estime that had the bad luck to be released in the same year as a little phenomenon called Platoon. Luckily, Stone directed that one, too.

The fervor for the latter – which was immediately declared the definitive American take on the Vietnam war on its way to winning four Oscars, including Best Picture – quickly turned Stone into the liberal conscience of a country reeling from two terms of Reagan and heading into a George H.W. Bush hangover. Most of the films that followed – Wall Street, Born on the Fourth of July and JFK – attacked the post-Vietnam, feel-good status quo by questioning the details of how the country got to this point. JFK is the apotheosis of Stone’s anti-authoritarianism: it’s a top-down indictment of nearly every political figure who came to power subsequent to Kennedy’s assassination; on the surface, the film dares to suggest that, even today, we are living under an installed government.

The point of Stone’s cinema is to raise more questions than could possibly ever be answered, and the fact that he does it under the guise of drama makes it far more defensible than the documentary fabrications of Michael Moore. At his best, Stone challenges everything you thought you knew about history; via a canny, technically peerless melding of hysterically loaded form and content, he forces you to reconsider the standard line while being skeptical of rampant conspiracy theorizing (JFK is a wonderful dichotomy: it’s brilliant, rousing propaganda that’s fully aware it’s three-quarters full of shit).

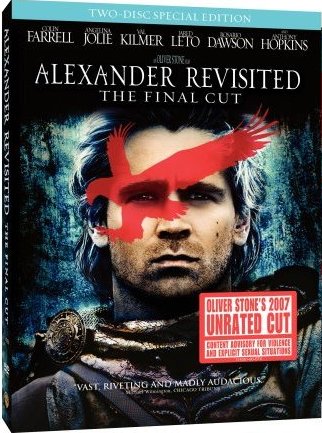

Stone’s cinema doesn’t always agree with me, but there’s great value in being challenged by a master manipulator of the medium. We don’t get much of that nowadays. Does this mean we now need to pay heed to his "final, final" cut of Alexander (just released to DVD, Blu-Ray and HD-DVD as Alexander Revisited), which runs a full fifty minute longer than his "Director’s Cut" of two years ago? Perhaps. To be honest, I haven’t had the time to take it all in. For now, I think the real reason to pick up this new release is to watch the documentary Fight Against Time directed by Oliver’s son, Sean. As Sean explains in the below interview, it’s an impressionistic look at an overwhelmingly large production, one that Stone père was forced to wrap in under ninety days due to budgetary constraints. This is insanity; though I’m not suggesting it could’ve come close to equaling the brilliance of this film, this would be akin to a studio demanding David Lean complete Lawrence of Arabia in six months. Corners are going to get cut, theme is going to get muddled, and whatever lands in theaters is going to be a compromise.

While I for now consider Alexander an artistic failure, it does have flashes of filmic majesty, particularly in the battle sequences. I’m also pretty sure it’s better than The Hand. Regardless, the opportunity to sit down with Oliver and his son Sean for an hour-plus interview at Warner Brothers last Monday was a no-brainer; it’s not often that you get this kind of at-length access to one of the most important filmmakers of the last fifty years. What’s wonderful about these lengthy roundtable discussions (which I hope the good folks at WB and Carl Samrock will keep coming as they continue to release director’s cuts and vintage titles), is that they afford you the opportunity to pick over the filmmakers’ entire oeuvre; ergo, you’ll read some illuminating stuff about JFK, Nixon, Natural Born Killers, Scarface and even The Hand (which to the delight of maybe myself hits DVD September 25th)!

This is close to the unexpurgated transcript. Please let me know if it’s too much. I hope you enjoy.

Q: When we talked to you during the junket for the theatrical release of Alexander, you weren’t a fan of the DVD format. Have your feelings changed now that DVD has allowed you to do several cuts of your movie?

Oliver Stone: Yes. DVD gave me a creative freedom I’ve never had before. This was an unrated three-hour-forty-five-minute cut, which would’ve been unacceptable in theatrical exhibition terms. They just don’t do it anymore. I grew up in the 1950s, and we had roadshows all the time. And the intermission aspect of it was like theater today; if you have an Act One, Two and Three, you can get out in the middle, take a breather, and think about what you’ve seen. That was the right length to this movie. It always was. It was in the script. Unfortunately, I didn’t [initially] see it quite that way; I was arbitrarily trying to make this movie three hours or less. So, as you know, I made two cuts of it. About two-and-a-half years after the film was released was when I worked on this – during the editing of World Trade Center. And I was finally able to come to peace with myself, letting the whole script express itself. It has a different pace, this film; the emotions come out differently. And the intermission comes at the right spot: it comes when Ptolemy and Alexander are in the mountains and deciding to go into India, and Alexander says, "We must make an end; we must find an end." It just has the right feel for me.

Q: Is this really the "Final Cut"?

Oliver: Yeah, I can’t do anything more. This is it. (Laughter)

Q: It’s just that you didn’t refer to this as your cut.

Oliver: I didn’t even bother. I called the second one the "Director’s Cut" because I thought that would be the end, but, in fact, two-and-a-half years later, I would call this "Revisited". But this is it. I promise you I won’t be back. (Laughter) All the footage is here, and this is the film I’m happiest with. DVD does give you that, and although I may have disparaged the idea that people are looking at films on smaller and smaller screens… it’s a shame that people have to watch DVDs with the lights on in a television-type situation where people are wandering in and out of the room. Movies are different from television, and you cannot watch movies like television. It distorts it.

Q: You mentioned the old road shows, and the way that these films used to play – like David Lean films. And in the documentary, Sean mentions that you had to pull Alexander together in less than ninety days. I know David Lean had a lot longer to make Lawrence of Arabia, and, yet, this film strives for that scale. When you have that limited amount of time, how do you bring all of these elements together to make something that is as big, hopefully, as Lawrence of Arabia?

Q: You mentioned the old road shows, and the way that these films used to play – like David Lean films. And in the documentary, Sean mentions that you had to pull Alexander together in less than ninety days. I know David Lean had a lot longer to make Lawrence of Arabia, and, yet, this film strives for that scale. When you have that limited amount of time, how do you bring all of these elements together to make something that is as big, hopefully, as Lawrence of Arabia?

Oliver: You can’t do it anymore. I think Ridley Scott is the perfect example, with Kingdom of Heaven and Blade Runner. He wanted to make more ambitious films, and he finally got the chance with DVD. I don’t know how, because exhibitors have cut it off. They have to make so many shows a day, it’s impossible to sell a three-hour forty-minute movie. I could never have gotten this through the system; it would’ve been a scandal. I have thought of alternative scenarios. Since you guys are mostly buffs, I would say to you that if I had had the guts, which I don’t think I had, I would’ve released a three-hour forty-five-minute cut in Europe. They probably would’ve done it. Remember, we were truly an independent film; we were financed essentially from Europe, an English-French co-production. I probably would’ve released this version in Europe and given it Warner Brothers, and they would’ve probably cut it. It would’ve been the typical Sergio Leone scandal, and I don’t think I’d be here right now. (Laughter) It’s just this system. You live in this system.

Q: Since this is an art form that costs millions and millions of dollars, what does an artist do?

Oliver: You can’t make big movies. You have to make smaller movies. You can’t take on Alexander unless you figure out a way to do it for less than three hours – which is possible. I couldn’t do it that way. Honestly, it does cut down your ambitions. Because some movies do take longer. There is a breadth to them.

Q: Does that mean that in the future you would won’t go for that kind of scale, or that you’ll look for other options?

Oliver: If seventy–five percent of the revenue is coming through DVD, you have to assume that there is a possibility of doing this, but you have to do it for DVD – unless an occasional theatrical would break through. But I don’t see that happening because who would put up the money for these kinds of things unless DVD becomes highly profitable?

Q: Would you be able to live with compromising for the theatrical release knowing that you’ll get your Director’s Cut somewhere down the line?

Oliver: That’s a very good question. You don’t set out to do a DVD cut and a theatrical cut, but perhaps because of the nature of circumstances, now we have to think that way. But, no, I would go for the best on theatrical.

I had a very short [production period on Alexander]. There are two versions of this story, but David Lean [said] he did not start cutting [Lawrence of Arabia] until it was over. In other versions, it was cut during. But, honestly, when we finished this thing, we had four or five months to get ready for mix, and that was too short a time. And it was my fault. I thought I could pull it off, but I just couldn’t. I mean, I was happy with the film theatrically; I wouldn’t have released it otherwise. But it would’ve been a huge scandal to pull out [of the release date]. Marty Scorsese had done it two years before with Gangs of New York. He did take that extra year, but that was a different situation; we didn’t have the money to do that because of the interest rate. It would’ve been an enormous problem for us, so we had to get it out.

Q: Did you see Sean’s documentary before it was approved for the DVD? At times, it’s not a flattering picture of what filmmaking is like.

Oliver: Sean was courteous enough to show it to me before, and I made some suggestions, but only for filmmaking reasons. I was embarrassed about some things in it, but I said, "Fuck it! I’m going down anyway with this movie. I might as well tape the whole thing." (Laughter) It wasn’t very flattering at times, but there was a special moment in our relationship because he was coming of age. And it was the first time we really had truly spent time together in a working environment over a long period of time, which was very good for him to see and for me to bond with him. He was shooting at weird times, but he was my son. Had it been a documentary crew, it would’ve been more difficult for me. He was in the hotel room, and on the way to the set, on the way back from the set… I mean, these are key moments for a director to say things they wouldn’t normally say.

Sean: I’m curious as to what you’re thinking of when you say "more embarrassing" or "private" things. There’s the aspect of the budget and producers, but from [Oliver’s] point of view I don’t see why that would hurt at all, because it only helps the audience understand what kind of pressure the director is under. That was the intention behind most of that: understanding what this project means, how big it is, how much money, how many people are working on it, and what’s on the line. You can understand the process better by this.

Then there was the personal aspect, which is the father-son relationship, which is what we were exploring towards the end. Actually, he incited it; he was the one who encouraged me to put the camera more on myself and introduce myself as a character. Initially, it was just going to be about him, purely as a portrait of a director.

Q: Oliver, there are some scenes with you going back and forth with the producers over money. Is that a variation of a conversation that happens on every movie?

Q: Oliver, there are some scenes with you going back and forth with the producers over money. Is that a variation of a conversation that happens on every movie?

Oliver: Oh, definitely. I would say it’s even more intense. I’m glad he caught that scene because we’ve had several conversations like that. I happened to have a great producer on this show: Moritz Borman. He was truly an independent. And the fact that we had French and German partners gave me… when Warners saw the first and second [theatrical] cuts, they would’ve cut all references to sexuality and all of the gorier stuff. All of the primitive warfare that you just saw, they would’ve cut that. They would’ve probably simplified the story enormously; the eunuch would’ve been gone. It was a very tough one to get through.

Q: Those cuts would be for getting the proper rating?

Oliver: No, we knew we were in for an R-rating. It was just to avoid an NC-17, but I think we got through that, Rosario Dawson withstanding. (Laughs) The eunuch was the biggest problem, I think, in terms of sexuality; the fact that he was a military commander who had Greek proclivities was not easy, because that’s not the way Americans like to think of military people. But the eunuch was a real hang-up. He was chopped out of the theatrical version. And I’m glad he’s back because he brings a humanity to Alexander when he’s dying; you see the emotions in the eunuch’s face. That’s part of allowing the emotions to play themselves out.

Q: Do you think production documentaries take on the face of the film that they’re talking about naturally? Or was that something created in the editing room?

Sean: The only thing I had as a model was the Apocalypse Now piece, Hearts of Darkness, which was very well done. It really gives you a sense of what that shoot must’ve been like, how hellish it was. And then, of course, I liked Lost in La Mancha. But, when I went into it, there wasn’t much that I was working with as a model; it was something where I shot everything over eighty-something days with 100 hours of material. I didn’t really know what I was doing. (Laughs) I didn’t catalogue it, so at the end I come back to it and I start working with an editor, and we just had to go through it. We had to watch and categorize all the interviews we had, and the material we had. Out of that, you kind of start to build a story. He often was saying, "Why don’t you shoot the clock, and pay attention to the time, and do a day in the life of a filmmaker and how stressful that is?" Well, I didn’t want to do just one day. I had so much material, and nothing that just added up to one day. So it was trying to do a metaphor by using three or four different locations, and giving you an impression of arriving on the set in the morning time, the slow build-up. And then how you get through one day, and then will be in the editing room until ten or eleven at night. You really don’t sleep much. You get home for like six or seven hours, and then you’re back out to the set. Some of those days you really did finish at five in the morning. It was insane.

Q: How inviting was the cast and crew to your filming? We see one moment where Colin says, "Fuck off with your documentary bollocks!"

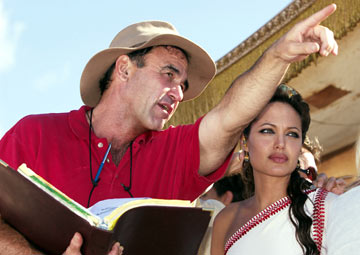

Sean: Colin was great, actually. That was a joke for him. It wasn’t intended to be nasty. That’s just his humor. But when [Oliver] was dealing with actors, I didn’t want to intertwine into that relationship that he had going, so I would try to stand back and get some audio bytes if I could. But mostly I respected that distance. I would take the actors separately, approach them, start a conversation, and just deal with them independently. Angelina, for example, made sure I made an appointment for the interview with her because she has her own PR people and a lot of security. Val Kilmer I’ve known since I was seven, with The Doors, and he was just great joking around all the time. But because I was [Oliver’s] son, and I was there every day, you do break down the barriers.

Q: Oliver, is it difficult to direct when you have cameras lingering around? It was obviously more impersonal when you had to contend with EPK (Electronic Press Kit) crews.

Q: Oliver, is it difficult to direct when you have cameras lingering around? It was obviously more impersonal when you had to contend with EPK (Electronic Press Kit) crews.

Oliver: It’s very difficult, talking to actors especially. It’s the most personal stuff. Each actor requires a different language. It’s very personal. It’s like sex; sometimes you don’t want to be filmed doing that. But if anybody is going to do it, I think your son… and I had committed to the idea that he was going to work with me. He started as a soldier in the phalanx, actually, and after doing that for a few days, he switched over. Then he was behind camera. As I said, I committed to being honest. He may have cut out some stuff that may have embarrassed me.

Q: Was the presence of the cameras ever irritating?

Oliver: There were times I was irritated, yes. Things would not go well, you know. But, as I said, it was a warts-and-all kind of thing. I knew this project was going to be a tough one, and that the chances of its success would be very tough. So if you’re going to sink, you might as well go down in all its glory.

Q: How do you split your time between the tent (Stone sets up his video village, a bank of monitors where the director watches each take via video, under a big black tarp) and talking to the actors?

Oliver: I balance it out. When the take is done, I’m out there mixing it up. I keep a hands-on relationship. I don’t want to make it remote. If anything, it’s very touch-and-feel, like looking in the face of the actor. But the tent is crucial because it’s an objective perception. And I had many cameras, too, so I had to look at various cameras. But it’s a way to really concentrate because the one thing you lose on the set is the script. The script is the bible. What is your original intention in this chaos, this puree, this noise, this money, all of the thousands of issues of everyday. You often lose sight of what was the original intention. And having worked on the script so hard… every time we would roll, I would basically have the script in front of me. And when I was in doubt, I would look at the line and try to remember the moment of the writing. That helps to balance out the madness. That’s why [the tent] exists: you need a sacred place. If you’re out there all the time in the noise with horses and elephants and dust, you become so externalized that you lose your internal.

Q: When do you feel you’re at your best on set, and when do you feel you’re at your worst?

Oliver: I’m at my most when I arrive. (Laughs) It’s hardest when you arrive because so much has to happen. And I think I’m at my best towards the end as I’m getting it. When you’re getting it, you really feel it. Sometimes you get the essence of the day in the late morning, and sometimes you don’t get it until after lunch. But the important thing is to get it. If you feel you don’t get it, that’s really frustrating.

Q: At the beginning of the documentary, Sean talks about how you were so prolific as a director during his childhood. You were making films at a year clip. In 1991, you had two films come out: The Doors and JFK. You were a machine in the sense that you were really locked-in. And with every film, there was a certain expectation: when you went to see an Oliver Stone film, you knew you were getting a certain kind of experience, what with Robert Richardson as your cinematographer, and the use of different film stocks and so on. Finally, in 1997, with U-Turn, you shifted gears. Was it that you got bored, or that you had exhausted that style of working and that you had to pull back?

Oliver: I think the latter would be the case. U-Turn was the eleventh film in twelve years. But it was ten films in ten years [from Salvador to Nixon]. We had worked at a pace that was incredible. I mean, one film a year of that size, that energy – and you can imagine the details that went into those films. They were huge films. They were muscular and big. And I do think we reached a natural exhaustion point. And then, in 1996, I edited a novel I had written earlier [A Child’s Night Dream]. I really worked on the novel; I went back to writing. U-Turn was a smaller film done with a smaller budget; it was done quicker. So I was tired. Then, when I did Any Given Sunday, I re-exhausted myself again, because that was probably one of the most difficult experiences, having to stage those football games. And then Alexander, with the documentaries in between. The pace has let up, but the intensity has not. And, actually, World Trade Center was exhausting. There was so much dust, and to shoot in those conditions, that was physically exhausting to all of us. So I’d love to do a little drawing room drama. I’d love to do Gosford Park. (Laughter) Q: Around the time JFK came out, you became the go-to guy for conspiracy theories. I’m sure you must have some opinions about what’s going on now. (There’s laughter, as well as an audible groan from one of the publicists.)

Q: Around the time JFK came out, you became the go-to guy for conspiracy theories. I’m sure you must have some opinions about what’s going on now. (There’s laughter, as well as an audible groan from one of the publicists.)

Oliver: Listen, I think the obvious has been missed, which is that the conspiracy these days has been so overt. You don’t need to hide it. There’s no need for covertness. If the President of the United States has been caught leading us into a war under false circumstances and everyone knows about it, that *is* a conspiracy. And no one seems to have impeached him for it.

Q: But we really need our agitators at this point. I think it’s interesting that you’re going to do Pinkville next, which is about the My Lai Massacre, and here we have another filmmaker of your generation, Brian De Palma, who’s doing a film about Iraq [Redacted]. I think it’s interesting that… it seems like you might want to attack what’s going on right now by going back to what you know best and what you’ve done best. Is that what you’re doing with Pinkville?

Oliver: I’m not going back to Vietnam per se; I’m going back because it’s a hell of a script [written by Mikko Alanne]. In 2001, it came in, and we worked on it. It’s more like JFK in that it’s an investigation of how things get covered up. I think that’s an old fashioned genre. In a sense, it’s a crime thriller, because a crime happens but it’s covered up, and it takes the tenacity and the veracity of two, three, four… actually, more men, but two main men to really uncover this crime. Because it was buried. People forget that My Lai did not come out for a year-and-a-half, and it was only in dribbles and drabbles. I didn’t even know as a soldier what exactly had happened until I read Alanne’s script in 2001. So the full implications of it, people still don’t remember. And certainly the new generation doesn’t remember. I think there is an historical obligation to remember. If we don’t remember, we’re really fucked.

Q: You still bounce back-and-forth between directing other peoples’ work and writing your own scripts. How does that work?

Oliver: When I’m working with another writer, I tend to make a lot of effort. When I collaborate with a writer, I’m not interested in credit, but I’m feeding him stuff all the time that I feel is important to shaping the script. We’ve been working very hard on Pinkville. We’ve had about eight drafts since 2001.

Q: Many people stop being writer-directors at a certain point and just become directors. Could you see yourself doing that?

Oliver: No. I love the act of writing. I like the quiet, internal aspect of it. If I lost track of that, I couldn’t direct the same way. I couldn’t be a director for-hire; it’s just not my nature. (Pause) I take that back, because you’re going to catch me one day. (Laughter) If there was a script that fit my sensibility to a T, I would take it and I wouldn’t change a word. But that hasn’t happened yet.

Q: We talked to Shekhar Kapur yesterday for Elizabeth: The Golden Age, and he was asked if there were parallels to contemporary issues. He said, "Of course, there is. Otherwise, what’s the point of making the movie?" Do you agree with that?

Oliver: I think we can only see the past through the conditions we live in in the present. Therefore, we’re conditioned. The past assumes the nature of the present. Certainly, Elizabeth means something to Shekhar Kapur in terms of today. We’ll see what it means when I see the movie. I’m a history person; I love history, so I don’t look for that necessarily. But I am conditioned by the present.

Q: Have you every thought about looking forward? Have you ever thought about doing a film depicting where you think society is headed?

Oliver: I’ve tried. I’ve developed several sci-fi projects over the years. I wrote The Demolished Man years ago. I wrote Conan the Barbarian as a sci-fi. But I’ve never been happy enough to make [that kind of] film. It’s a high-level field; you’re going into Kubrick-land, Ridley Scott… there have been some great sci-fi films, and I don’t want to make a half-assed film. It’s not my area of expertise. But that’s not to say it won’t change. I will say, in answer to your question, that the reason for Alexander… is that Alexander is one of the greatest inspirations. He’s an example to the youth of today – of leadership, of guts, of bravery, of following your dream. True, at the same time, with inspiration there is also misery and suffering and burden that he had from his youth. But I wanted to show the young generation that there are heroes; there are people who can change the course of history – for better or for worse. In Alexander’s case, it’s one of the greatest models, and I think we’ve forgotten that – especially in America. They know Alexander much better abroad. We did much better in Japan. (Laughs)

Q: Looking at the full range of your films, all of your protagonists have something in common with Alexander, whether they’re charismatic and self-destructive, or going up against impossible odds. Do you think this is an outgrowth of your interest in Alexander, or is he just another character in that line?

Oliver: I would say that Alexander was in that line of people; otherwise, I wouldn’t have focused my life around Alexander. As a young man, I read Mary Renault’s books, and they much moved me. And then I read Robin Lane Fox’s great biography from 1972, which gives you a very Western-oriented overview of it. Alexander is a prototype. You realize that when he went to the East with this size Army, no one had done that. All the Greek mythic heroes had gone east, but they were myths. Achilles was a myth. Perseus, Theseus, Hercules… they probably existed in some form. But they all went east. That’s where a Greek went to make his bones so to speak. And Alexander was the first man who actually went east not to plunder, not to loot and come back to Greece – which is where the Macedonians wanted to go back with the money. He stayed. And he became half-Eastern. That was the interesting thing about his journey. It wasn’t like "Let’s get out of Iraq." He went over there to stay. He probably didn’t know that at the beginning, but there was something that chased him out of Greece. I hypothesized some of it had to do with his mother. Why didn’t he ever bring his mother out to see him? It beats me. But I’m fascinated by the idea of this man. He did something that no one’s ever really done before. Even the Mongols went home.

Q: There’s a quote in the documentary: "Perfection is the enemy of good." I’m wondering if you can elaborate on that. And did you always feel that way, or did it take you some time to come to that conclusion?

Oliver: That’s my personal idiosyncrasy. It’s a French expression. Perfection *is* the enemy of good. You do hear of these cases of the Kubricks of the world who do take after take in search of perfection, but I think that’s an illusion. I really do think that it’s subjective. The kinds of films I’m making, which are fairly large and ambitious… and they’re controversial, and you can’t get a lot of money to make them. I say you have to settle. Get the overall. Some of my films may have been crude at times, or tough, or missed the points, but I’ve tried to get the overall in. I think that’s more important. You may miss a thing or two, but you move faster. If you can do it in three takes, do it in three takes.

There’s the great story with John Huston and Jack Nicholson, where he said to Nicholson, "You got one take." And he didn’t believe him. But he actually did have one take, and he got it right. I’ve been on sets as a writer before where actors would warm up with the first take. I don’t believe that. I think you should do rehearsal and work at it, but when the camera rolls, you should be ready. I think Clint Eastwood would agree. Try to make it good the first time.

Q: The Hand is coming out on DVD in a couple of weeks. Have you looked at it? Is there anything different about it?

Q: The Hand is coming out on DVD in a couple of weeks. Have you looked at it? Is there anything different about it?

Oliver: No. That was an early work. It’s flawed. But the last time I saw it a year-and-a-half ago, I thought some of the dialogue was really good. And the story is based on a good thriller. Michael Caine’s performance in interesting. It’s a strange movie; it’s an uncomfortable blend between the psychological and the horror. I was pressed to put more horror in there. I was a young filmmaker, and I had a good dose of studio pressure there.

Q: As an experienced filmmaker, do you think, "Hey, there’s some good stuff in there," or do you obsess on the mistakes?

Oliver: I see the mistakes, yeah. But I think there’s some very good stuff. It did take a beating. I did not work as a director for four or five years until Salvador, and I had to do that off-lot with British [producers]. I suffered for that film. But it did make money, ultimately, for Warners.

Q: You talk about how you knew you were going down with Alexander. At what point of the production did you feel that, and how did you then rear your shoulders up and keep going?

Oliver: You know, I felt the same thing on JFK: that this was going to be the end of me. I really did. It was another three hour-plus movie, the dialogue was cerebral, there was enormous amounts of difficulty, it was a complex screenplay and a very complex edit. I didn’t think it would make it, and I was amazed when it did. It resounded as it went around the world. JFK was a huge hit. So I guess that emboldened me to keep going, but I knew that one day I would come to this point that I would make something so outrageous and so ambitious that… it’d be that Don Quixote feeling, that I’d have to tilt at a windmill. Sometimes you’ve got to do it. That’s the only way you can do things.

Nixon was a setback for me financially, far worse than Alexander. Alexander did well abroad, and will make money for its participants. Warner Brothers is doing well with it on DVD. But Nixon was the biggest setback; we spent $42 million, I think, and we grossed $13 million. I love that movie; it’s one of the most ambitious I’ve made on the political scene. But it just did not take. I guess the character of Nixon was not attractive to American people or foreign people. That was the worst setback. But people who write about the setback of Alexander are wrong. My worst period was Nixon, Heaven and Earth and U-Turn. Those were the three least performing pictures I directed.

Q: Sean, my favorite part of the documentary is when you confront your father with what the critics have said about him – in particular, the charge of heavy-handedness. How did you work up to that? Was there some trepidation there?

Sean: No, I think that was one of the first questions I asked. (Laughter) It’s important to have a good ongoing dialogue, and [Oliver’s] never been shy about hiding things from me or talking to me about those things. Honestly, I think it was one of the first things we were talking about. It’s one of the things critics do reference: heavy-handedness. Aside from the conspiracy theorist thing, which sort of gets thrown as a jab.

Q: Oliver, how do you draw the line between being an artist and a businessman?

Oliver: I think you can maintain two tracks. I think you have to. That’s what this kind of filmmaking is about. If you’re not aware of the limitations of what you’re up against… it’s like a general: you have to know your artillery and you have to know your infantry. You have to know what you *have*. You have to marshal your forces and use them well. It comes down to the personal and the intimate, but at the same time you have to have the big picture.

Q: Given the television landscape today, is there anything you’ve thought about developing for maybe HBO or F/X?

Oliver: I produced films for television, including Wild Palms for ABC back in 1993, which was pretty advanced for its age. But I would work in television if I had no choice. It’s not a hot medium. It’s a cool medium: people walking out of the room, the lights are on, your wife or husband is talking, your kid is talking. It’s mind-boggling. It’s a medium in which you can miss something and come back to it. But film… I make my films like you’re going to *die* if you miss the next minute. You better not go get popcorn. (Laughter)

Q: Don’t you think shows like Heroes and Lost have afforded people the opportunity to bring a more film-like attitude toward television.

Oliver: Well, they have. Television has usurped everybody from film. And so have commercials, by the way. In a sense, we’ve democratized the image. If you look at the techniques of JFK and Natural Born Killers, they’re all over commercials now, all over TV, all over the place. I see them so constantly that I feel that it’s a degeneration; there’s no point or purpose for it. To the contrary, stylistically, I would go the other way like with World Trade Center, where you’re really concentrating on the acting, the lighting and the story. This is what we are: we’re storytellers. There are reasons for stylization, but let’s do it better than television. The stock is great, and they have access to digital. Everyone has DI [Digital Intermediate] now, and they can make their films look great. But, for some reason, television still bores me. Even the best shows. I’m not a Sopranos fan, I hate to tell you.

Q: You talked about how your aesthetic was appropriated by commercial directors. They took the look of your films to sell product, and now there’s no meaning to it.

Oliver: It’s not just me. They’ve taken from all of us. A lot of the good cameraman who we used are doing television work; they’re doing commercials for a lot of money. And the commercials look incredible. But what’s it about? I made three major commercial campaigns. I enjoyed it, I experimented with it, and at the end of the day I felt no satisfaction. It was like having a fast food lunch.

Q: But when you consider how people have gotten used to your aesthetic in the hands of other people, did it force you to completely change? And was that frustrating?

Oliver: I would never go back to the style of Natural Born Killers. You always try to find the right style for the movie. That’s the key. Every movie requires its own style. Just be honest to the story. Tell the story in the best possible way that is different, exciting and original. But with television, the image has been degenerated, no question. With the internet, commercials… people are much too cynical about image. It’s stale. And all over the world, not just America. I was on a plane two days ago from Asia, and you can’t believe the flatscreen images on the plane. So what can you do? You have to find another way.

Q: With movies becoming more television-like, especially with the glut of ads and previews beforehand-

Oliver: Oh, god.

Q: -how do you make sure that film stays unique?

Oliver: It’s very difficult. When I go to the movies, and I have to sit through ten previews of films that look [alike] and tell the whole story, you know that we’ve reached an age of consensus. And consensus is the worst thing for us. We all agree to agree. That’s where we lose it as a culture. We have to move away from that. That’s what I’m trying for, and what I hope [Sean] is trying for. I would like to see originality. It’s so difficult.

Q: Sean, what are your ambitions as a filmmaker, and does it help that your father’s an established filmmaker?

Sean: I’m not sure yet. (Laughter) I wouldn’t have been able to get this documentary done if that weren’t the case. This was a unique circumstance. But on the other hand, I’m proud of the work. And I’m now doing a documentary for the Nixon DVD release from Disney next year. It’s a featurette about Nixon; we did about eighteen interviews with people from that time period – historians, politicians, law professors. Beyond that, we may be able to take that material and do a feature documentary with it. Long term, I love writing and I’d like to direct ultimately. But in the meantime you have to do what is available to you, and documentary is what I can do now.

Oliver: I just want to say that he’s a little modest. He’s cut a a thirty-four minute documentary called "Beyond Nixon". Nixon is very specific to our age because we have another president who’s gone way beyond Nixon. So what he’s done is remind us of who Nixon was, what he did, and it’s a very succinct documentary – very good writing and especially writing. The interviews he did with people from Gore Vidal to John Dean to reposition Nixon in this era to remember who he was for young people.

Q: With that in mind, a natural fit for you would be George [W. Bush]. With the father, the son, the war and conversations with God, it sounds like something right out of a movie. Is that something that might interest you?

Oliver: (Big smile) Yes, very much so. (Laughter and applause.)

Q: When?

Oliver: Soon.

Q: How soon?

Oliver: Soon, soon.

Q: Sean, what did you learn about your father as a filmmaker from doing this documentary?

Sean: I mean, he’s one of the masters as far as I’m concerned. What I saw from filming him actually made me much more aware of why he is such a great director. Direction is a thousand choices, a thousand decisions a day. And having a vision of what you want, and then knowing what you want frame-by-frame, second-by-second… if you don’t have it laid out in the design and in the way the actor performs it, it’s not going to happen. So for somebody to craft that mentally, it gives him the opportunity to develop the story over time. And he always chooses the right people to work with; he always has a great sense of who would be right for what role in terms of actors, but also for the crew – what kind of DP, art director, set designer, costume designer. He knows every aspect of the filming process. Then, of course, the editing process… he’s there every day. Shooting all day, going into the editing room at night, looking at the material, covering it, working with the editors hands-on. That’s a total filmmaking process, and I don’t know what to compare it to because I’ve never seen other directors work. But you can see that in the output: this is someone’s vision. When you see so many films [that are a] consensus form of cinema, where they have a certain look because the studio or producers or director are limiting themselves, saying "It has to look this way, and this is the standard form of performance"… then, when you see a film like Alexander, it does challenged the audience. And it’s something that has to be done. You have to challenge people to reconsider what is art, what is taste. Because it’s someone’s point-of-view. I think that’s the strongest thing he offers: you’re going in to see an Oliver Stone film, and you’ll know it’s an Oliver Stone film. You may not like it, and you may disagree with things, but you get art.

Q: I remember reading your script for Nixon, and it was like 300 pages. What is your writing process like? Do you edit yourself when you’re writing, or is the script the bible and we’ll worry about how long it’s going to be later?

Oliver: I’ve fallen into that trap. My scripts do tend to be long. I wrote Nixon with two other young men, Chris Wilkinson and Steve Rivele, and they really did a great job. Nixon was a mind-twister, but it’s a wonderfully structured script. I love the way it’s structured about that life. It is a story of his life, but it’s unlike other biopics I’ve seen because of that structure. The structure was very important, and the length was three hours and ten minutes. (Sighs) What do you do about it? You cut the script as much as you can to get to the essence. But some lives take time. I don’t know what the answer is, except DVD. (Laughter)

Q: You’ve done a lot of Director’s Cuts of your films. Is there a particular film you’d like to revisit like you’ve done with Alexander?

Oliver: No, I’ve done what I’ve wanted to do. There’s an unrated cut of Natural Born Killers which I prefer; it was released briefly by Lionsgate. And there is a director’s cut of JFK where I’ve added some scenes to make it longer. Nixon‘s got a director’s cut, which is longer.

Q: Is that the version you’re doing for Disney? Will it have new footage?

Oliver: No. It’s the director’s cut with additional scenes, but they’re more integrated. Before, we didn’t have the technology to integrate that. Right now, it’s the best looking cut, but it’s the same cut.

Q: Forgive me if this is a touchy subject, but what’s your relationship with Quentin Tarantino? We understood that there was a great falling out over Natural Born Killers over what you did to his script. Do you guys talk?

Oliver: I’ve talked to him many times since then. We do get along. He was upset at the time; he was a young filmmaker, and he was upset that we changed… not his story, but the screenplay quite a bit. We put more emphasis on other things. He was upset, and he came out publicly.

Q: By that same token, when you were a younger writer, you had your screenplays turned into very notorious films – in particular, Scarface. It’s an indelible work. It’s really impacted the culture in a huge way and, some might say, in a pernicious way, because some people misinterpreted the meaning of that film. How do you now view the film and the reaction to it.

Q: By that same token, when you were a younger writer, you had your screenplays turned into very notorious films – in particular, Scarface. It’s an indelible work. It’s really impacted the culture in a huge way and, some might say, in a pernicious way, because some people misinterpreted the meaning of that film. How do you now view the film and the reaction to it.

Oliver: I always thought it was a satire. I never saw it as threatening to be reality. It never sought to be The Godfather. I think Brian was the right director for it because he has the necessary sarcasm. There is a lot of humor in the film, but it was sort of lost at the time because of the bloodbath, the violence and the viciousness of the characters. My model with it was twofold: one was Bertolt Brecht’s Arturo Ui and the other one was Richard III. Those were the models, and they were not exactly reality models. But the film was attacked for being literal. Natural Born Killers was attacked for being literal, and it wasn’t. As you know, with Wall Street they took the Michael Douglas character and made him into a role model, which was not intended. You can never judge how the film will be taken; you can only make your best effort, and put out what you feel. How it’s read, you never can tell. Or remembered for that matter.

Q: Could you ever see yourself working in another medium? Opera seems like it might suit you.

Oliver: For length purposes? (Laughter)