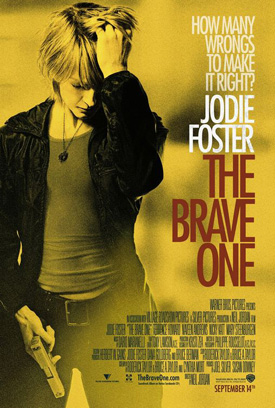

Neil Jordan’s The Brave One positions Jodie Foster, finally, as the butch badass we’ve always known waited within her. He goes so far as to let us watch her transformation from a blithely happy woman in love to shattered gunslinger, and Foster, for her part, plays it well. She looks so natural blowing away kids on the subway.

Neil Jordan’s The Brave One positions Jodie Foster, finally, as the butch badass we’ve always known waited within her. He goes so far as to let us watch her transformation from a blithely happy woman in love to shattered gunslinger, and Foster, for her part, plays it well. She looks so natural blowing away kids on the subway.

I may be able to deliver some vague praise for Foster, but I can only shake my head at the film around it. What exactly are Neil Jordan’s intentions with this grimly hilarious revenge picture? That’s right, it’s a comedy. Unintentional to be sure, but when a film commits the twin offenses of being silly and high-minded, laughter is the only recourse. Every deep cackle this movie provoked was like one of the bullets from Jodie Foster’s gun, aimed straight back at Jordan’s efforts.

Don’t mistake The Brave One for a female revenge movie. This isn’t Jordan’s version of Ms. 45 or I Spit On Your Grave. He’s actually entered a genre much less publicized: urban revenge.

New York City is really the entity out for justice. It smacks Foster’s complacent character around for daring to believe that her city is really as nice and safe as she believes. At times, I also felt that Jordan was hoping to slap the audience that pines for the good old days when New York was a battlefield, the playground of The Warriors and Death Wish, not The Nanny Diaries.

As Erica Bain, Foster wanders the city with a microphone and recorder, capturing the sounds of a disappearing landscape. On her radio show she spouts wordy, insipid eulogies for the old New York. Away from work, however, she’s thrilled for the future, which includes a marriage to fiancée Naveen Andrews.

But you can’t mourn New York’s ugly bygone years embrace the peaceful future at the same time. Not according to Bruce and Roderick Taylor’s script, anyway. So, on a late walk through Central Park Erica and her fiancée are set upon by Hispanic thugs. She’s beaten within an inch of her life, he’s killed and their dog is stolen. New York has its revenge.

The rest of the film is like an absurdly strung out third act with a finale that is both hollow and exceptionally dumb. Foster gets a gun, apparently learns to use it between firing her second and third shots and heads straight into the state of mind that has Bernie Goetz as governor. Killing number one is arguably justified but followed by a string of gunshots that are purely criminal, all part of the breakdown instigated by the attack in Central Park.

Before she learns to kill, that breakdown shuts Erica out of the city. Her home, once welcoming, looks shadowed and terrfying. She can barely leave the house.

The gun changes everything. She can’t tolerate the handgun purchase waiting period, so she buys one off the street. With her hand weighed down by the steel, she feels safe. "I walk the streets at night now," the voiceover says, "and I see things I’ve never seen before." That’s lovely. Translation: Erica never knew her city, the real city, before she had the gun.

It’s also wildly funny thanks to Foster’s uber-serious delivery. She could be reading indictments at Nuremburg, her voice is so cold and, grr!, determined! Also wonderfully comic are the aftereffects of Erica shooting a would-be pimp through his windshield and every interaction she has with Mercer, the detective investigating the string of unsolved shootings suddenly plaguing Manhattan. The tone shift created by unintentional laughter is damaging like a pipe bomb on a bus, and the aftereffects get worse as the film tries to take itself seriously despite howls from the audience.

Jordan manages to make Terrence Howard, as Mercer, utterly ineffectual, even weak. He focuses on the actor’s combination of soft-spoken nature and steely eyes, but I never bought him, not even for a dollar. Mercer and Erica develop a sort of relationship, and he suspects her for the shooter early on. Can he really not prove his suspicions, or does he just want to fuck Erica? Does he want to rail her while proving his case? He doesn’t manage to make me care either way.

This concoction is difficult to swallow at every turn, but there are moments that bring light to the background. Nikky Katt stands out as a detective partnered with Howard. Often relegated to cheap comedy relief, Katt goes beyond the jester stereotype. With gang tattoos on his neck and madly cropped hair, he implies a backstory of violence and reform before a word is spoken.

The Brave One finally delivers the promised revenge but implicates Mercer, in a bit of scriptwriting that wouldn’t pass muster in a special needs workshop. It’s the most shallow, poorly written ending you’re going to see in an ‘important’ studio picture this year. I promise that. It also stands against swathes of social values. Trying to legitimize a sub-genre that is inherently irrational, Jordan has only legitimized mindless vigilantism because a pretty white girl was victimized. See it with your entire neighborhood militia.