America is in distress. There. I just saved you two hours and ten bucks.

America is in distress. There. I just saved you two hours and ten bucks.

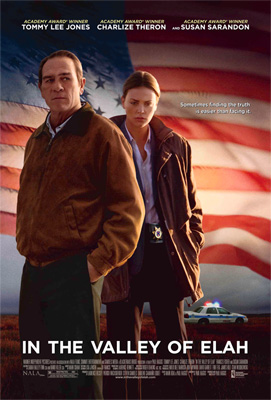

But if you’re still hot to see whether Paul Haggis has matured as a storyteller after ramming Crash down your gullets, In the Valley of Elah offers signs of progress; even though every perception shift is, once again, too telegraphed to affect viewers with active antennae, Haggis at least invests the stock procedural elements with an urgency that keeps you watching even when you’ve long since decided the film is full of shit. A lot of this has to do with Tommy Lee Jones, who is devastating as Hank Deerfield, a career military man forced to conduct his own unofficial investigation into his soldier son’s stateside murder when the Army investigators circle their wagons and attempt a cover-up. We’ve seen Jones in this kind of role before, but it’s rare to see that gruff, know-it-all facade crack and ultimately crumble; and it’s the power of Hank’s personal journey that partially excuses his seemingly mystical powers of deduction.

In theory, Haggis is after something commendable: the humbling of the patriot. And the guy who directed Crash might’ve dragged Hank’s personal politics into the narrative, thus turning this into an all-caps screaming match about the validity of the war in Iraq. Instead, Haggis, for once respecting the audience’s intelligence, assumes that we’ll take Hank’s hawkish support for granted; one look at Jones in close up, and we’re positive this guy hasn’t questioned the justness of American foreign policy since Vietnam – and, even then, he probably believed that was just a failure of resolve.

Men like Hank are all resolve; they’re the shitkickers we turned to after 9/11 for an infusion of pride, the kinds of guys who don’t admit defeat even when they’re tits up on the canvas. They’re bruisers; they take it for granted that they’re going to knock you flat on your ass. That’s why Hank’s post-Army profession, hauling gravel, is so amusingly appropriate. You wouldn’t want to be on the business end of a truck weighed down with that stuff.

There isn’t an actor alive who embodies the above attributes as certainly and invigoratingly as Tommy Lee Jones (R. Lee Ermey is too unhinged); from loyal bulldog in Rolling Thunder to common sense-spouting federal marshall in The Fugitive, we love Jones when his jaws are clenched. Though he’s willingly subverted this righteous ferocity in films like JFK, Blown Away and Ron Shelton’s deeply underrated Cobb, I’ve never gotten the sense that those performances stuck in the public’s consciousness. For most folks, when Jones steps into the frame, business is gettin’ handled, and woe betide the fool who stands in his way.

But when Hank leaves Tennessee for Fort Rudd in New Mexico upon learning that his son, Mike (Jonathan Tucker), who’s just returned from Iraq, has gone missing, we’re already too far ahead of him thanks to a clumsy framing device (which intermittently parcels out a troubling phone conversation between Hank and his boy). Hank already knows Mike is fucked up over something. That he comes to realize, via secondhand epiphanies, that it’s the war and not just Mike that’s fucked up is one of the narrative’s biggest flaws: Hank served in Vietnam; if he could make his peace with the atrocities and failures of that conflict, the fact that Mike has been exposed to equivalent misconduct shouldn’t come as a shock. Bad guys do bad shit. Just don’t be a bad guy. It’s that simple.

If it’s the notion that his last surviving son – in an underdeveloped subplot, Hank’s wife, Joan (Susan Sarandon), resents her husband for having lost Mike and another son to war – could be weak enough to be impacted by the rigors of urban warfare, then who needs the procedural? Jettison the useless B plot concerning civilian detective Emily Sanders’s (a wasted Charlize Theron) struggle for acceptance from her male peers (which she clearly does not deserve since her critical breakthroughs in the case come courtesy of Hank’s master sleuthing), and dig into the central conflict of a true believer fighting against the military bureaucracy.

Of course, if Hank was any kind of true believer, he’d zip up and let the Army handle the investigation however they please, and that’s where In the Valley of Elah gets into serious trouble. Yes, most fathers would question any institution no matter how hallowed to ascertain the truth of their son’s death, but the frustrating fact about guys like Hank is that they do not question. Ever. They just do. That’s how they got those medals. They may piss and moan about red tape and pencil pushers, but, at the end of the day, the only boat rocking they’ll do is to stand up and bust the dissenters in the chops.

The minute Hank starts to question, he’s no longer Hank, and the rest of the film is just a preordained journey to the fluttering of an upside down flag. (And in case you didn’t know the significance of an upside down flag, Tommy Lee is good enough to explain at length in the opening moments of the film.) This is when the Haggis of Crash, so sedulously repressed throughout most of the film, comes roaring back, replete with a gooey Annie Lennox music cue. At this point, even the galvanic power of Tommy Lee Jones isn’t enough to keep your eyes from rolling.