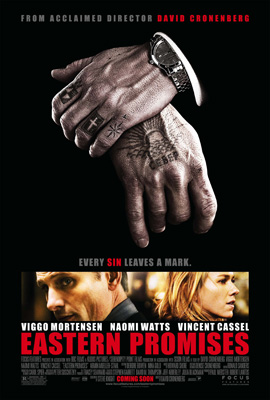

The twisted team of David Cronenberg and Viggo Mortensen prove persuasive enough to distract from screenwriter Steven Knight’s parade of contrivance and convention in the Russian mob melodrama, Eastern Promises. Though far from Cronenberg’s best, the director is certainly more comfortable within the confines of the prestige picture than he was a decade ago with the muddled M. Butterfly, and that’s cause for muted celebration. The difference this time is that Cronenberg is actively fascinated by the milieu depicted in the flawed material, and he dramatizes it with a heightened sense of brutality that offsets the screenplay’s laughably disingenuous feints at compassion.

The twisted team of David Cronenberg and Viggo Mortensen prove persuasive enough to distract from screenwriter Steven Knight’s parade of contrivance and convention in the Russian mob melodrama, Eastern Promises. Though far from Cronenberg’s best, the director is certainly more comfortable within the confines of the prestige picture than he was a decade ago with the muddled M. Butterfly, and that’s cause for muted celebration. The difference this time is that Cronenberg is actively fascinated by the milieu depicted in the flawed material, and he dramatizes it with a heightened sense of brutality that offsets the screenplay’s laughably disingenuous feints at compassion.

By all rights, the screenplay’s framing device, which pits the upended morality of the Vory V Zakone brotherhood (as it exists in the London underworld) against a kind-hearted midwife, shouldn’t work at all, but when the crisis-of-conscience is embodied by the ever alluring Naomi Watts, attention must be paid. She’s terrific casting as Anna Khitrova, the London hospital employee who becomes dangerously invested in the welfare of an infant extracted from a dying, drug-addled Russian teenager. Aside from the baby, the only clues to the young girl’s past lie in a business card for the Trans-Siberian Restaurant and a diary. Though Anna is of Russian descent, she is not fluent in the language; ergo, she hops on her vintage motorcycle (surely a Cronenberg addition) and rides straight into the nerve center of the Russian mob to get the diary translated. This is hardly rational behavior, but Anna’s need to place the baby with relatives lest it be lost to "the system" is curiously all-consuming; unfortunately, it’s also entirely transparent, as one knows Anna’s mission is driven by a frustrated maternal instinct well before her cruel Uncle Stepan (Jerzy Skolimowski) mumbles said exposition over dinner – though Knight opportunistically compounds her misery by introducing an interracial element for added, culturally intolerant effect. In other words, Anna may be leery of Semyon (Armin Mueller-Stahl), the very connected owner of the Trans-Siberian, but she’d rather farm out the translation of the diary to him because… he has yet to impugn her black ex-lover?

Knight’s setup couldn’t be more ham-fisted, but Cronenberg draws out Watts’s eroticism via wardrobe (she’s often clad in a black leather riding jacket) and, most importantly, her verbal thrusting-and-parrying with Mortensen, who turns in the performance of his career as Nikolai, the driver and caretaker for Semyon’s reckless imbecile of a son, Kirill (Vincent Cassel). As in A History of Violence, Cronenberg has wisely paired Mortensen with one of the most irrepressibly sensual actresses working today; the difference here is that Nikolai is already a very bad boy, while Anna couldn’t be more of a naif. But damn if she doesn’t want to get it on with the heavily tattooed, flamboyantly coiffed mobster, who, as she digs deeper and deeper into the life of the deceased girl (which, shock of shocks, might lead back to someone in Semyon’s family), might be a direct threat to her well-being. There’s potential for some trademark Cronenberg kink in this conflict, but Knight isn’t adventurous enough to entertain such untoward thoughts.

What’s more, Cronenberg – again, for the first time since M. Butterfly – seems acutely conscious of his perverse past, and, for once, leaves the audience surrogate relatively untainted. The restraint is admirable in that Cronenberg is attempting to break himself of old habits, but this feels too much like a concession to accessibility. Anna is never in danger: she’s a moth to the pane. As a result, Cronenberg grows bored with her and, additionally, the plight of the baby – which is a good thing because it allows him to pour his energies into depicting the extreme menace of the film’s mobster milieu.

This shift of focus is significant enough to temporarily elevate the film from flawed to near-great. Indeed, the second half of Eastern Promises belongs to Nikolai, who, through his actions in defense of Semyon’s family, rises from chauffeur to the Vory V Zakone version of a "made man". Though there’s an obvious, unspoken angle being worked by Nikoloai, Mortensen’s charismatic but unsentimental characterization goes a long way toward keeping the audience off-balance until the underwhelming reveal. And yet that looming letdown is effectively overshadowed due to arriving on the heels of a third-act bathhouse tussle that sets a queasy new standard for realistic hand-to-hand combat in film. Going mano-a-mano minus attire against two (disappointingly clothed) assassins brandishing some nasty looking blades, one expects Nikolai to undergo a History of Violence-style transformation into an unstoppable killing machine, but that’s not quite what happens. Nikolai’s more of a brawler; while he may eventually overpower his attackers, they’re going to get their lumps and stabs and slashes in. There’s nothing aesthetically pleasing about this fight; Cronenberg keeps the desperately bloody struggle going several beats longer than any other director could stomach. The grand guignol beauty of Cronenberg’s gore is gone, replaced by a stunning realism unlike anything he’s captured before.

The awfulness of this sequence should draw some figurative blood from the audience as well, but Anna is completely removed from it; her actions may have been a catalyst for the confrontation, but they’re too tangentially related to register emotionally. The viewer might be periodically unsettled, but they get to shake off the residual muck the minute they leave the theater. The same goes for the film; only the performances and set pieces linger in memory. That they’re exceptional enough to keep the viewer riveted for an expertly paced 100 minutes hardly excuses the pedestrian quality of the material. Eastern Promises has more to do with career advancement and critical plaudits than provoking thought by upturning the eaten-through underbelly of the London underworld. It’s "Slumming for Trophies".