I’m really struggling with the fact that the lads behind VICE Magazine have created a film that is human, touching and fully divested of put-on scenester bullshit. Heavy Metal In Baghdad applies the magazine’s DIY aesthetic to a story that is genuine, political and moving. There’s not an ostentatious tale of drug use or even a pithy, bitchy comment on fashion. This is a layered documentary about young men in very dire straights, and a very good one at that.

I’m really struggling with the fact that the lads behind VICE Magazine have created a film that is human, touching and fully divested of put-on scenester bullshit. Heavy Metal In Baghdad applies the magazine’s DIY aesthetic to a story that is genuine, political and moving. There’s not an ostentatious tale of drug use or even a pithy, bitchy comment on fashion. This is a layered documentary about young men in very dire straights, and a very good one at that.

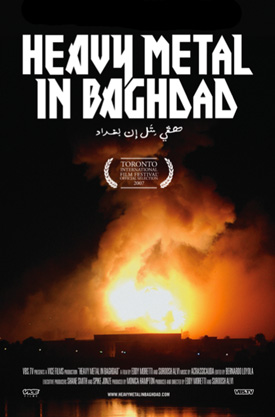

Acrassicauda claims to be the only heavy metal band in Iraq. I don’t see any way to dispute that assertion, so we’ll run with it. In 2003 VICE ran an article on the group and has sporadically kept in touch over the years. Prior to this film, the magazine sponsored the combo’s last gig in the war-torn city, at a hotel that is now completely walled off. In 2006, VICE co-founder Suroosh Alvi and co-director Eddy Moretti went to Baghdad in an attempt to reconnect with the band and see what the war has done to their lives and music. What begins as a travelogue, with Alvi and Moretti seemingly only a few steps removed from the Jackass boys as they make their way to Iraq, ends as a sobering portrait of civilian casualties and refugees. Superficially, the four musicians look like any metalhead you’d meet in the American southwest. They have goatees and lopsided smiles. They wear black t-shirts advertising Pantera, Sepultura and Metallica. With the exception of the quiet guitarist, who speaks through his instrument in shredding solos, they speak fluent and often eloquent English. They’re not a particularly good band, but positively glow with enthusiasm and belief in metal. "Our songs are not about politic," singer Faisal says early on. But every subtitled lyric is a vision into a civilian Iraqi’s view of the war delivered in a guttural, blasted vocal. If this isn’t politics, what is? But that’s the difference between living a war through the news and living it on the ground. It becomes part of life, not abstracted into politics, and Alvi and Moretti let that fact seep in rather than trying to hammer it home. So at the end of the film, when the band is living as a group of refugees in an unheated basement in Syria and some express a wish to go home, it’s not a shock. Even with the war, life at home might be preferable to living as an unwelcome immigrant abroad. (Politics for the band, incidentally, might be like the song they were once made to perform in praise of Saddam; during his regime, public performances were required to pay tribute to the leader, and Acrassicauda’s metal bow to the man is one of the film’s biggest laughs.) Alvi tries to downplay the danger of making a film in Iraq. ("People would say it’s really fucking stupid for us to be doing this, but heavy metal rules.") Still, he emphasizes the need for security, lingering on the expensive hired detail. He persistently goggles at the inability to move freely through the city. The restrictions on Alvi and Moretti’s movements are a belabored point. I was irritated when they forced the security detail to stop and hang out near the river just for the sake of doing so. Still, the civilian foreigners’ reaction to the dangers of a war zone is more than grandstanding. While the filmmaker’s vulnerability probably can’t be exaggerated, the danger to Alvi and Moretti is also a window into the danger faced by Iraqi citizens. Band members are careful not to be seen with the Western journalists, strictly adhere to the nightly curfew and avoid certain neighborhoods when traveling through the city. Bass player Firas claims that simply wearing the metal shirts he prefers is inviting kidnapping by insurgents. As elsewhere, the film is canny enough not to point out the obvious point there. Having grown up a metal fan in the late ’80s, in a town that didn’t appreciate the genre’s symbols and attitude, the film hit home. Metal is a badge of identity for a lot of fans, certainly for me at a young age. But being accused of Satan worship in Iraq is a very different thing than in Texas. America sought to bring democracy to Iraq; little did we know that the true spirit of rock and roll was already there. Firas also refutes descriptions of the civil war as sectarian conflict. He’s a Shiite and his wife Sunni. Insurgent violence, he says, is simply the result of diverse power hungry groups rushing in to fill the void left by Saddam and the West’s inability to create a power structure. Not that the reasons matter. Fans who attend one of the bands shows might never be seen again; their practice space and gear are destroyed by a rocket; their families are in daily danger. Heavy Metal In Baghdad lingers because Moretti and Alvi found a natural and stark conclusion. As in granddaddy doc Gimme Shelter, we see the band reviewing a rough edit of the film. Their reaction to bygone gigs and the destroyed practice space is focused and genuinely pained. The last moments with Acrassicauda are indelible and raw, and as clear a vision of their daily lives as anyone might want to endure.