We’ve been deluged, it sometimes seems, with portraits of troubled musicians. The musical biopic has become a popular sub-genre; it sells soundtracks by the millions and raises familiar public figures up to a level of adoration and/or scrutiny that we’re all comfortable seeing. It’s just so easy to watch the dissection of a rock star’s life. Thanks, VH1.

We’ve been deluged, it sometimes seems, with portraits of troubled musicians. The musical biopic has become a popular sub-genre; it sells soundtracks by the millions and raises familiar public figures up to a level of adoration and/or scrutiny that we’re all comfortable seeing. It’s just so easy to watch the dissection of a rock star’s life. Thanks, VH1.

Even so, I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say there’s something special about the life and work of Ian Curtis, singer for the Manchester band Joy Division, that makes him an ideal subject.

His sub-baritone delivery and jittery stage presence made the perfect compliment to his band’s bouncing, howling songs. Joy Division were both bleak and trance-inducing; Curtis provided an unlikely glimmer of star power, and made the band heavyweights in the UK. Then, literally on the eve of their first U.S. tour, he hanged himself in the flat of his estranged wife.

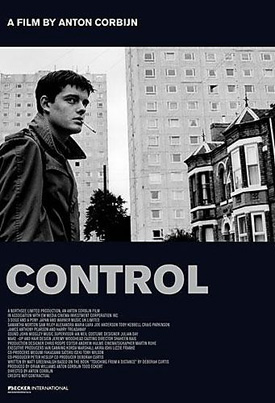

His ‘X factor’ not at all in doubt, this sketch directed by rock photographer Anton Corbijn and based on a memoir by Curtis’ wife Deborah still has elements common to the classic rock downfall. The early marriage; a child; a mistress. Finally, an inability to handle fame, and the depression that follows.

I’m not feeling as positive about this particular version of the music biopic as I was when I walked out of it. Control possesses several unquestionable marks of quality: a breakout performance from Sam Riley as Ian Curtis; an eye and ear for live music that uncannily captures Joy Division’s particular presence; and a visual sense that equally communicates the rock scene in ’70s Manchester.

No surprise that photographer/director Corbijn is interested in aesthetics. He loves the clothes of the period and is transfixed by the blocky, imposing row houses that make up sections of Joy Division’s city. And when it’s time to recreate a televised performance, he does so unerringly. Watch early band performances on YouTube after catching this film, and you’ll be hard put to distinguish between some of the footage.

Surely, the film is almost excessively beautiful. Every shot is perfectly composed. Grey tones are warm and gorgeous; the skin of Ian Curtis often glows. The film feels like a shrine to his visual appeal.

But Corbijn’s eye, dominated by beauty, misses important elements. He rarely pegs the import of Manchester as a character, and as an influence on the sound and lyrics of Joy Division. He makes Curtis’s first encounter with an epileptic fit seem almost like the event that triggers his own epileptic condition. And he avoids providing illustrative context whenever possible. Control is necessarily interior, focused as it is upon Curtis, but it describes a vaccuum of existence that’s difficult to believe, even knowing the singer’s depressive nature.

Some of this is almost a given, given the screenplay’s source material. We see the band implicitly through Deborah Curtis’s eyes, and her perception colors great swaths of the film. That leads to a singular vision of Ian (she seemingly never recognized his depression) and a detachment from the working core of the band. The film therefore is frequently flat and one-sided. For example, do you know the names of the other members of the band? If not, you won’t learn anything from Control.

Smart of Corbijn, then, to hire actors capable of transforming a small bit of dialogue and screen time into something lasting. You’ll remember each of the three band members by action if not name, and probably want to hire manager Rob Gretton (brilliantly played by Toby Kebbell) as your own personal guidance counselor. But that seems like the result of smart casting and a director who let these high paid background artists go about their own business while he attended to Ian and Deborah Curtis.

Aside from a few bright moments featuring Alexandra Maria Lara as Curtis’s Belgian lover Annik Honoré, Control rides a shallow emotional curve. There’s the illusion of movement as each musical performance provides an elegiac high. But despite Samantha Morton’s good work opposite Riley, the movie just marches inexorably on towards Ian’s suicide. And that moment, while not gauche enough to force us to look at the hanged man’s dangling feet (fuck you, 24 Hour Party People) does still take the easy way out when it’s time to deliver the coup de gras, asking Morton to scream like she’s in a Friday the 13th film at the discovery of Ian’s body.

It’s a worthwhile, if superficial, compliment to pay a music biopic that you leave wanting more of the artist. And while I’ve never been a huge Joy Division fan, I’ve spent the days since this screening constantly humming ‘Transmission’ and ‘She’s Lost Control’. But that doesn’t blind me to a deeper understanding of the film’s failings. With the Grant Gee documentary Joy Division also on hand as a companion piece, I’m willing to let Corbijn and Deborah Curtis get away with their version of events. I’m just not willing to take it as gospel.