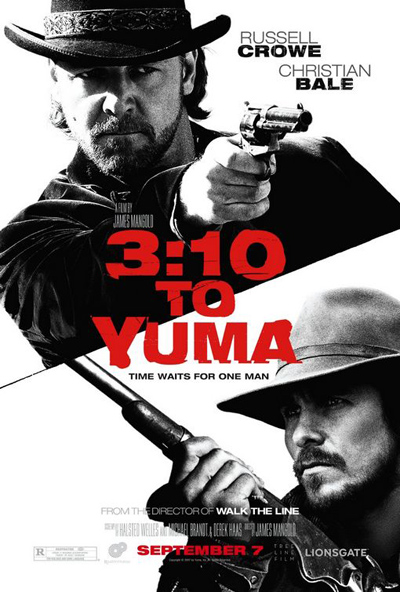

When a legendary outlaw and a mild mannered rancher set on bringing him to justice lock horns, who wins?

When a legendary outlaw and a mild mannered rancher set on bringing him to justice lock horns, who wins?

Up and coming actor Ben Foster.

While Christian Bale and Russell Crowe are the above the title talent in this film, it’s Foster who’s the real draw, stealing the spotlight from the charismatic man from Down Under and his grim-faced co-star. Foster plays Charlie Prince, the infinitely loyal right hand man to Crowe’s desperado, Ben Wade. Foster plays Prince as a wounded man who has found a father in Wade, but also as a cold, merciless murderer who more often than not finds killing the most expedient solution to his problems. While Wade and Bale’s rancher, Dan Evans, have their journey and their battle of morality, it’s Prince’s single minded quest to rescue Wade from the law that gives 3:10 To Yuma its oomph.

Foster brings menace to a movie that needs more of it. Prince is unpredictable in the way of the best cinematic sociopaths; Foster never hams it up because he understands that while he’s in a mythological western and he’s playing a character who is bigger than life, hamming it up would kill the illusion. So Foster bottles him up instead, playing the madness only through his dark, dancing eyes.

The movie needs Prince as a villain because the supposed bad guy is too noble for words. Russell Crowe’s Wade comes across more as a rogue than a murderer, a more ruthless, more sober and less gay version of Captain Jack Sparrow, perhaps. Anyone who has seen a movie will know that the arc of Wade’s character must lead to some kind of redemption, so all of his sparring with his captors rings hollow. We’re told that he blew up a train full of pioneers, but the only killing he does onscreen are mercenary agents of the law or people we’re hoping will bite it. Even his womanizing has a soft edge – after bedding the local bar wench he sits and sketches her nude form. It’s a Leo moment!

Wade is a rock star among outlaws (a thematic element explored more fully and more satisfactorily in the far superior The Assassination of Jesse James By the Coward Robert Ford), and we can see the film’s main conflict being set up when the son of one-legged, on the verge of losing his land rancher Dan Evans is seen reading fantabulizing outlaw fiction. When Wade is captured, Evans volunteers to help take him to the town of Contention, where they will catch the titular train that will take Wade to prison, where he will be hung for his many crimes. There’s a fee involved, which would get Evans out of his massive debt, but it’s also a chance for the man to be a man, at least in the eyes of his son. And maybe in his own eyes, considering the history Evans doesn’t like to talk about.

The film is a remake of a middling western from the 50s; the script by Michael Brandt and Derek Haas essentially adds a second act to the story, creating a danger-filled journey from the Evans ranch to Contention. Along the way Wade’s escorts are picked off one by one as they encounter Apaches, renegade railroad men, a grossly distracting Luke Wilson, and Wade’s gang, set on springing him from custody.

This is not bad stuff; the second act almost crackles at time. The western is a fine, pulpy genre, and the second act of 3:10 To Yuma pays homage to that sense of boy’s adventure, of men camping out in rocky outcroppings and always aware of the branch snapping approach of an Indian raiding party. It’s the first act that sets the film off limply; the script and director James Mangold spend too long establishing what a chump Evans is. I think that Christian Bale’s ‘I’ve never enjoyed anything, even a blowjob from my wife, played by Gretchen Mol,’ performance sells that plenty well without hammering it home to the point that liking Evans feels like masochism. Obviously Wade is the guy to root for here, since he at least retains control of the muscles one uses to smile.

But maybe that’s the point. By the time the third act rolls around we get a lot of people sitting around contemplating right and wrong and cowardice and duty, and when Wade makes the choices that lead to his inevitable redemption, they honestly feel like charity, since Evans is such a goddamned Debbie Downer. Can he bring the first smile to this man’s face? Considering that they’re locked in a hotel room together for hours, the film could have obviously explored some fascinating avenues in answering that question.

What does happen, though, is that the film sets up a tremendously great problem – Charlie Prince offers all the townspeople of Contention money to kill anyone holding Wade, and a whole fucking lot of people throw their guns into the ring – without a real idea of how to solve it. There’s a good contrast here, of people doing wrong for money while Evans is doing right for money… or maybe something more than that. Whatever the case, it never feels like the film uses this conceit properly, and just gets rid of it when it becomes too complicated its own good. To the film’s credit it does just get rid of it during a long and loud gunfight, so it’s very possible that once the squibs start going off most of the audience won’t even mind that the promise of a morally tinged toss down has been trashed.

James Mangold stages his action with complete competence, but without sizzle. This is a very middle of the road film, one that will never get your heart racing or piss you off too much. The world of cinema needs directors like Mangold, who make movies that are mostly OK, if only so we can pinpoint the people who watch these films and think they’re great. Mangold’s films are perfectly middlebrow, without any elements that could confront or test us, and with just enough signifiers of quality to make you feel like you’ve watched something finer than average. It’s like when fast food places use fancy bread. Let’s put it this way: Mangold is on a career trajectory right now that could see him getting a Best Director Oscar before Paul Thomas Anderson. He’s just that safe.

Which is not to say that 3:10 To Yuma is a bad film. It’s a fine enough movie, if overlong, and when it sheds its pretensions it approaches the levels of a fun movie. There’s something funny about westerns these days – they can’t just be fun genre movies. Of course that’s sometimes wonderful, like with The Assassination of Jesse James By The Coward Robert Ford, a film that should be in the running for Best Picture if there is a God, but once upon a time the western was a junk genre… and I kind of like that. Imagine if thirty years from now cop action films or science fiction films are only prestige pictures – how sad would that be? I love the idea of using a supposedly debased genre to tell a sublime story or to find universal truths, but sometimes I also like to just see guys on horses being badasses and shooting each other. When 3:10 To Yuma is providing that, I am happy. But too often the film decides this is not enough, and it yearns to be more important than it is. Cutting many of these scenes out would bring the film’s running time to a more manageable hour and forty minutes and streamline it into something unashamed to be having a lot of fun.