Whenever a documentary breaks life down into a battle of good versus evil, it’s usually an indication that the filmmaker has plunged headlong into not only subjectivity, but prejudice. This has been especially true of the recent spate of political documentaries; in the absence of an overriding, absolute truth or a smoking gun, many documentarians, insecure in the commerciality of their work, will prop up a bogeyman for the audience to hiss at. But the universe doesn’t work this way. And this, as The Rules of the Game‘s Octave would remind us, is the awful thing about life: "Everyone has their reasons."

Whenever a documentary breaks life down into a battle of good versus evil, it’s usually an indication that the filmmaker has plunged headlong into not only subjectivity, but prejudice. This has been especially true of the recent spate of political documentaries; in the absence of an overriding, absolute truth or a smoking gun, many documentarians, insecure in the commerciality of their work, will prop up a bogeyman for the audience to hiss at. But the universe doesn’t work this way. And this, as The Rules of the Game‘s Octave would remind us, is the awful thing about life: "Everyone has their reasons."

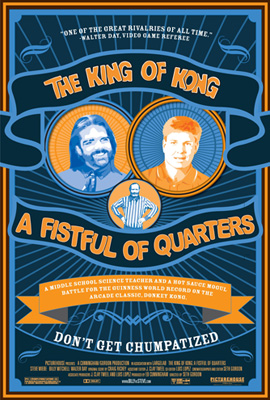

But what happens when those reasons are strictly vainglorious? What happens when someone is so blinded by pride, and so arrogantly convinced of their own greatness that they are unwilling to recognize it in others? This is the amusingly high-handed quality evinced by World Donkey Kong Champion Billy Mitchell in Seth Gordon’s immensely entertaining documentary, The King of Kong, and it is worrisome on two levels: either Mitchell is a victim of access (in that he didn’t grant enough of it to Gordon to allow for a well-rounded portrait), or he is one of the biggest assholes in existence. If it’s the former, than Gordon’s movie is as dubious as the above-mentioned political docs; if it’s the latter, then someone needs to cut this motherfucker down to size.

Considering the staggering levels of conceitedness and hypocrisy displayed by Mitchell throughout The King of Kong, it seems reasonable to accept the latter and, therefore, anoint Steve Wiebe as the Rocky Balboa of competitive arcade gaming. Hailing from Redmond, Washington, Wiebe is the ultimate underdog: most of the gamers in the official orbit of Twin Galaxies (competitive gaming’s governing body) are lifers; the legends, like Mitchell, have been at it since the early 1980s, while their proteges, like Brian Kuh, aren’t so much upstarts as disciples who’ve sought out the counsel of the best to ever play. It’s a harmonious, tight-knit group overseen by Twin Galaxies’ idiosyncratic founder and head referee, Walter Day. So when an outsider like Wiebe challenges the establishment, the gamers’ microcosm is thrown into turmoil.

As for why a happily married father of two like Wiebe would want to dedicate his spare time to conquering a twenty-six-year-old video game, Gordon posits, through interviews with family and friends, that it’s a need to see something through to its conclusion, win or lose. The myriad failures of Wiebe’s life are particularly excruciating due to their unresolved nature: he had a chance to pitch in the deciding game of the state high school baseball championship, but was stymied by a sore arm; meanwhile, his dream to be a professional musician was cut short due to a strange sort of self-sabotage (one of his friends comments that Wiebe essentially didn’t want anyone to know about his music). That Wiebe’s quixotic quest for the Donkey Kong crown began during a period of unemployment suggests that he is driven by pride. Here, at last, is something he believes he can conquer; so, to blot out yet another failure, Wiebe dedicates himself to breaking a record most normal human beings don’t even know exists.

It’s an unusual reaction to failure, but, then again, Wiebe is an unusual guy. He is also an admirably conscientious fellow, which he proves by traveling across the country to New Hampshire to break the Donkey Kong record in an official venue when his taped-at-home score is rejected due to irregularities in his machine (actually, it’s not so much the irregularities as it is Wiebe’s acquaintanceship with Roy "Mr. Awesome" Shildt, the scourge of Twin Galaxies). All of the veteran competitive gamers, and Mitchell in particular, preach the gospel of proving your ability in a public setting; videotapes can be manipulated, but there’s no denying blasting past 800,000 points with multiple eyewitnesses peering over your shoulder. The plot thickens, however, when Mitchell goes against his own creed and, in response to Wiebe breaking his record (and becoming only the second gamer in history to achieve a "kill screen" – look it up on your own), sends a tape to the Funspot arcade to undermine Wiebe’s freshly-minted achievement. Though everything about Wiebe’s videotaped score was scrutinized (Twin Galaxies even sent a pair of dorks to his house in Washington to tear apart his machine while he wasn’t at home), Mitchell’s is quickly accepted. For the gamers, balance is restored: Billy Mitchell is back on top.

If his personal history is any kind of accurate barometer, this is where Wiebe would fold and go home. But, for the first time in his life, he decides to man-up in the face of adversity; Mitchell, the Babe Ruth of competitive gaming, can keep sending in videotapes, but Wiebe is going to keep besting the legend on his own turf, in front of his own acolytes. This is where Gordon’s documentary becomes both inspiring and surprisingly affecting. By all rights, Wiebe’s undertaking should be risible; his decision to haul his family down to Florida to hang out at a hotel while he sits in an arcade all day trying to master a video game should be depressing. But sometimes you have to fight your personal demons on some very strange, very unexpected terrain, and there’s a sense that if Wiebe doesn’t follow this thing through to its conclusion, he might not be able to live with himself.

Though hardly a technical marvel, Gordon’s documentary engagingly evokes 1980s nostalgia (Joe Esposito’s cheeseball classic, "You’re the Best", turns up on the soundtrack), while confidently navigating the well-trod path of the sports film narrative. It also keeps giving Mitchell enough rope to hang his once sterling reputation. Unchecked arrogance is an appalling trait, and it’s a blast watching Wiebe deflate Mitchell’s pomposity just by being a good guy working within a system doing everything to make him fail. Deep down, you always knew the final battle between good and evil was going to be fought on a stand-up, coin-operated Donkey Kong machine.