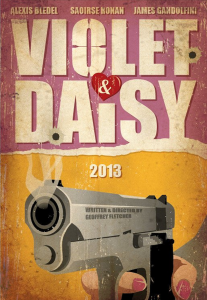

As Violet & Daisy opens with two teenage girls dressed as nuns knocking on the door of a NY apartment and blasting apart an entire room full of giant dudes, you may well start off thinking you’re watching an Abel Ferrara film in reverse. This is the directorial debut of Geoffrey Fletcher, who was plucked from toiling obscurity and churned through the accolade wringer in 2009, culminating in an Academy Award won for his adapted screenplay for Precious. With this follow up –which he wrote before Lee Daniels’ film hit it big– he steps into the directors chair for an even smaller and more strangely personal film that shares some of the subtle themes and textures of his controversial Oscar-winning screenplay. On top of his looks at unusual family dynamics, the nasty edges of city life, and an interest in friendship though, there is an extra thick layer of contemporary 70s throwback, hyper-real, chapterized fantasy surrounding this exploitation-style premise of two barely-of-age urban assassins.

As Violet & Daisy opens with two teenage girls dressed as nuns knocking on the door of a NY apartment and blasting apart an entire room full of giant dudes, you may well start off thinking you’re watching an Abel Ferrara film in reverse. This is the directorial debut of Geoffrey Fletcher, who was plucked from toiling obscurity and churned through the accolade wringer in 2009, culminating in an Academy Award won for his adapted screenplay for Precious. With this follow up –which he wrote before Lee Daniels’ film hit it big– he steps into the directors chair for an even smaller and more strangely personal film that shares some of the subtle themes and textures of his controversial Oscar-winning screenplay. On top of his looks at unusual family dynamics, the nasty edges of city life, and an interest in friendship though, there is an extra thick layer of contemporary 70s throwback, hyper-real, chapterized fantasy surrounding this exploitation-style premise of two barely-of-age urban assassins.

Daisy has just turned 18 and her jaded partner Violet is looking from a break from their non-stop schedule of contracted hits, that is until the release of the new dresses in a pop singer’s clothing line forces her hand and they accept a new job. The problem occurs when the job they’re tasked with ends up being an unusual one, with a man –though perfectly ready to be taken out– turning out to be a very difficult target. The film mostly takes place in a single apartment, is divided by chapter headings, features a dream sequence and some Guy Ritchiean crime scenes, and is exactly as strange and heightened as it sounds. The violence is often played for laughs, and there’s plenty of absurd humor stemming from how unapologetically the film accepts its own premise of two young girls –who despite their actual ages are certainly acting like stunted tweens– dealing death with disregard.

Even from this description I can feel your mind leaping to a Tarantino comparison, which will only be cemented once you actually hear the quirky dialogue, see the hyper-violence, and read the title cards. It’s a fair thought, as not only is the film transparently riffing on Tarantino’s contemporary exploitation cinema but the director is outright thanked in the credits. But while Fletcher is surely working in a similar post-Pulp paradigm, he succeeds in establishing his own closed-in little world, shot in a uniquely sharp style.

Fletcher’s partners in crime here are Saoirse Ronan (Hanna) as Daisy and Alexis Bledel (Sin City) as Violet- the two young women who are as likely to snack on suckers and gush over teeny magazines as murder a mobster. Though playing the older, jaded veteran who has gone through a few partners before, Bledel is still playing well below her years, while Ronan is the starry-eyed rookie. They live like sisters, with the film upholding a fairy tale disregard for any reality of how they might have ended up in these roles. Once Gandolifni enters the picture their dynamic lights up, as each develops her own relationship with the man, and both friction and the depth of their loyalty becomes more clear.

Fletcher’s partners in crime here are Saoirse Ronan (Hanna) as Daisy and Alexis Bledel (Sin City) as Violet- the two young women who are as likely to snack on suckers and gush over teeny magazines as murder a mobster. Though playing the older, jaded veteran who has gone through a few partners before, Bledel is still playing well below her years, while Ronan is the starry-eyed rookie. They live like sisters, with the film upholding a fairy tale disregard for any reality of how they might have ended up in these roles. Once Gandolifni enters the picture their dynamic lights up, as each develops her own relationship with the man, and both friction and the depth of their loyalty becomes more clear.

The film itself is captured with a keen eye; the clever compositions spice up the film and help seal the girls together as a team, all while conveying the tone of a heightened fable. Both the amplified tone and the creative camerawork both seem to dissipate towards the middle, though I suspect in the case of the former it’s merely the audience slowly coming into tune with the oddball universe Fletcher is writing within.

Of course, the not-so-hidden secret weapon of the film is James Gandolfini, operating in his rarely-exploited mode of mythic gentleness. It’s a great role for him, and he develops a unique chemistry with both girls, while soulfully anchoring this violent parable. The film is obliquely loaded with coming-of-age subtext, and Gandoflini’s presence actually shepherds a lot of those more potent themes to the surface. It’s a subtle, sad performance and would be worth a viewing even if the rest of the film weren’t so fascinating.

It’s a weird thing to need to note, but the film successfully avoids digging into any of the awkward sexual undertones that invariably come with films that juxtapose young women and violence. Even films not looking to titillate often still bend over backwards to diffuse sexual tension, and yet here there is no tension to diffuse- one of the girls even takes a shower and spends a scene wrapped in a towel. And yet, it all feels natural and safe here, which says good things for the earnest nature of all of the characters and how they’re captured.

It’s a weird thing to need to note, but the film successfully avoids digging into any of the awkward sexual undertones that invariably come with films that juxtapose young women and violence. Even films not looking to titillate often still bend over backwards to diffuse sexual tension, and yet here there is no tension to diffuse- one of the girls even takes a shower and spends a scene wrapped in a towel. And yet, it all feels natural and safe here, which says good things for the earnest nature of all of the characters and how they’re captured.

To more specifically describe the oddball character of Violet & Daisy would be a disservice, but if you enjoy watching films in which you really, truly have no fucking idea what’s going to happen next, you can’t miss this one. At times it borders on derivative and often flirts with crossing the line of preciousness (no pun intended), but it never loses itself and blasts its way through a 88 minute bloody yarn with energy and style to spare. Unmissable for the performances alone, Violet & Daisy is a perfectly gnarly fairy tale- sweet, stylish and bloody.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars