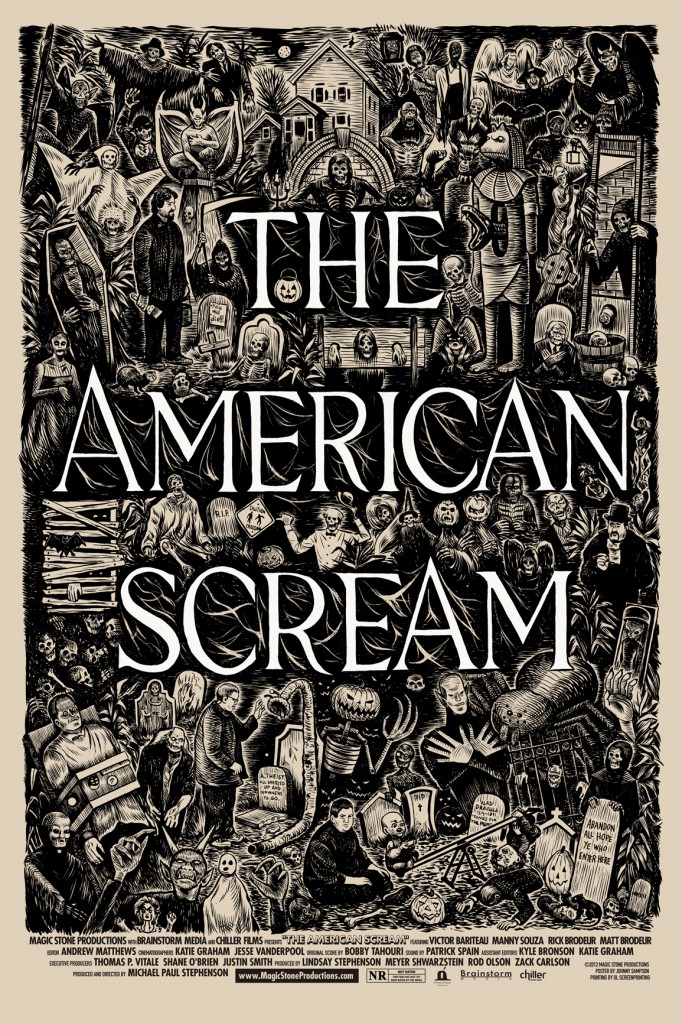

Three years ago, former child actor Michael Stephenson experienced a sudden career revitalization and metamorphosis when he decided to make Best Worst Movie, a documentary love-letter about the cult fandom surrounding his most notable acting credit, 1990’s supremely entertaining WTF crapsterpiece Troll 2. It would have been hard to not make Best Worst Movie a funny film. With almost too-good-to-be-true subjects like vivacious dentist George Hardy and cluelessly passionate director Claudio Fragasso, the documentary basically made itself. Stephenson just needed to point his camera in the right direction. But it was the ways in which Stephenson went further – past laughing-at detachment to something deeper and more emotionally resonant – that made Best Worst Movie a special film and hinted at a possibly untapped filmmaking talent in Stephenson. Stephenson’s newest doc, The American Scream, produced for NBC Universal’s Chiller network (and good enough that Chiller decided to also release the film theatrically), cements those hints. Stephenson is the real deal. I saw some astounding films at Fantastic Fest this year, from the restoration of Ted Kotcheff’s 1971 classic Wake in Fright, to the inspired romp I Declare War and the arthouse mindfuck Holy Motors. But no film at the festival had a greater and more immediate emotional impact on me than The American Scream. I cried. Moist happy tears. More than once. And it is a goddamn movie about people building haunted houses in their yard.

Three years ago, former child actor Michael Stephenson experienced a sudden career revitalization and metamorphosis when he decided to make Best Worst Movie, a documentary love-letter about the cult fandom surrounding his most notable acting credit, 1990’s supremely entertaining WTF crapsterpiece Troll 2. It would have been hard to not make Best Worst Movie a funny film. With almost too-good-to-be-true subjects like vivacious dentist George Hardy and cluelessly passionate director Claudio Fragasso, the documentary basically made itself. Stephenson just needed to point his camera in the right direction. But it was the ways in which Stephenson went further – past laughing-at detachment to something deeper and more emotionally resonant – that made Best Worst Movie a special film and hinted at a possibly untapped filmmaking talent in Stephenson. Stephenson’s newest doc, The American Scream, produced for NBC Universal’s Chiller network (and good enough that Chiller decided to also release the film theatrically), cements those hints. Stephenson is the real deal. I saw some astounding films at Fantastic Fest this year, from the restoration of Ted Kotcheff’s 1971 classic Wake in Fright, to the inspired romp I Declare War and the arthouse mindfuck Holy Motors. But no film at the festival had a greater and more immediate emotional impact on me than The American Scream. I cried. Moist happy tears. More than once. And it is a goddamn movie about people building haunted houses in their yard.

Fairhaven, Massachusetts is a prototypical quiet New England hamlet full of nice and wholesome people. Victor Bariteau and his wife and two young daughters are among those nice and wholesome people. But lurking inside their modest home, something dark brews throughout the year. Mild-mannered Victor is a “home haunter,” a special breed of Halloween enthusiast who goes the extra distance and transforms his backyard into a elaborate spookhouse and work of performance art every Halloween. Down the street, Victor’s friend, the burly New York City-esque Manny Souza, became inspired by Victor to start doing his own home hauntings. By sheer coincidence, across town, father and son duo, amateur clowns, and bickering roommates Richard and Matt Brodeur are also home haunters. Stephenson’s cameras trace the three families’ journey and struggles through their respect prep period, building up to the big day — Halloween!

Unlike Best Worst Movie, which had a hilarious film production to recount, a host of long-lost cast members to revisit, and two decades worth of bizarre fan growth to explore, The American Scream‘s subject matter is wispy. Home haunters are a mildly interesting topic, maybe enough for a solid five-minute news segment. But even with three different families to cut between, stretching the topic into a feature film sounds like a boring waste of time. These are just average people putting together complicated but completely inconsequential holiday decorations. No one is sinking their fortunes into what they’re doing. If they fail, what will happen? Kids will shrug and move on to the next house on the street to get some candy; which they’re going to do regardless. The stakes are non-existent. This is Stephenson’s challenge. And he succeeds by not bothering with “stakes.” There is no faux sense of urgency or drama. He is interested in the people and what motivates them to put so much work into something that will only exist for a few hours on a single night of the year. What he comes away with is of course very funny, but also shockingly moving and inspirational.

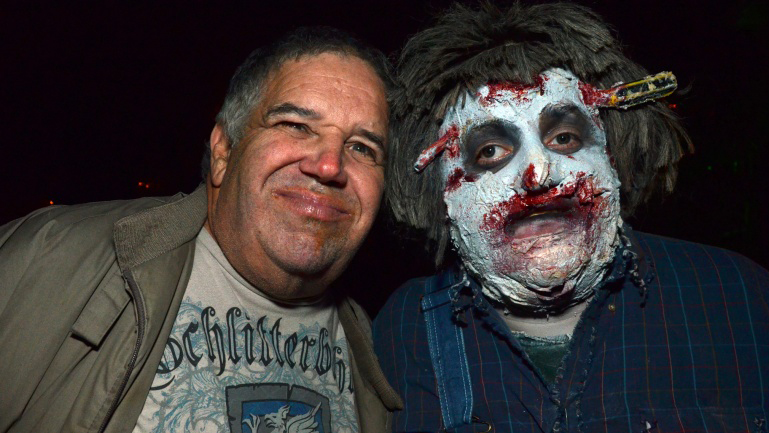

Richard and Matt Brodeur

Richard and Matt Brodeur are the film’s “comic relief,” one might say (if I worked at Chiller I’d already be thinking very seriously about turning them into spin-off reality show). Of the film’s three subjects, they have the worst, most incompetent home haunt. Their scenes are by turns funny, cute and endearing — and eventually perplexing and frustrating when we learn more of arrested-developmental Matt’s inexplicable disinterest in the romantic advances of his sweet female best-friend — but they also represent the less interesting aspects of the film. While Stephenson treats them with impartial objectivity, the Brodeur’s are nonetheless laughing-at characters. Seeing them blunder through prop construction and getting suited up for amateur clowning appearances is hilarious, but it never feels like Stephenson became fully engaged with the two men beyond their undeniable appeal as wacky oddities. This could have everything to do with the film’s production window, as Stephenson was already well underway making a film about Victor and Manny when he learned of the Brodeurs. Needless to say, Stephenson couldn’t pass up documenting yet another home haunter family in the same tiny town. Especially such strange ones. So Stephenson presumably did not have as much time to spend with the Brodeurs, to dig in as deep with the duo as he did with Victor and Manny. Whatever the case…

Where the film truly comes alive is in the stories of Victor and Manny. The two men are perfect counterpoints to each other. Victor is a clean-cut pencil-pusher. He’s reserved and a bit wound-up. He becomes obsessive and a perfectionist when it comes to his home haunts. For Victor it is an all-consuming hobby. Manny on the other hand is a lovable lug, a relaxed blue-collar mustachioed beer drinking type. He has a carefree “whatever” attitude to his home haunt, worrying less about the details and more about the bigger picture. While Victor meticulously constructs elaborate props and agonizes over set pieces, Manny takes pride in turning dumpster-diving finds into useable works of Halloween art. And unlike the Brodeurs, what makes the two men so equally compelling to observe is that they’re good. Victor is obviously more skilled and ambitious, but Manny is no less talented. Both men love and understand what they’re doing, and what works on their Halloween night patrons. The joys of The American Scream come much less from watching the two men prepare for the upcoming Halloween than from listening to them talk about past Halloweens. Getting inside their heads and lives is where Stephenson finds the film’s heart and soul.

The Souzas.

I’ve long held that there are basically two kinds of people: Halloween people and Christmas people (damn you Tim Burton and your genius cashcow idea for a movie!). As a Halloween person, The American Scream‘s initial appeal was an obvious one. But Stephenson has a way of surprising you by effortlessly (almost imperceptibly) sussing out a poignant truth lurking beneath the surface of his subject matter. In Best Worst Movie Stephenson turned the silly stupid story of a terrible film into a rousing examination on why we watch and love movies and why artists and actors put their whole lives into making them. The American Scream follows a similar path. Stepheson burrows beneath the surface of Halloween. The film actually got me thinking about why I love the holiday so much; realizing it wasn’t necessarily for the reasons that first come to mind. Though Manny is rarely seen without a horror movie related T-shirt on, neither man ever says much about the horror genre or monsters. A love of all-things-horror is not what motivates them to transform their yards into home haunts. It is about community. Yes, that is the secret macabre theme of The American Scream! In one of the many scenes that caused me to tear up in the film, we learn that Manny suffered a heart attack not that long ago, and had initially planned to give up his home haunting. But he was pulled back in by aghast neighbors who couldn’t dream of a Halloween without a visit to his yard. Here this unsuspecting guy, some schlub who works on a construction crew with no grander creative aspirations, has found a foothold in the memories of his town. With a proud smile on his face, Manny talks about a little boy who made his mother drive to Manny’s house every day one October to get a look at the gargoyle that Manny created for his front yard. You get the sense that with that one memory, with knowing that he positively impacted just that one kid, Manny could die a happy man. He isn’t an important man doing important things, yet the children of Fairhaven will grow up always remembering Manny Souza’s house and the same master of ceremonies costume he wore every year. And at the risk of being corny — that is kind of beautiful.

I still love Halloween, but, like most people, the choicest memories and experiences I had with the holiday are from my childhood. You don’t think about things like community when you’re a kid, but watching The American Scream made me think a lot about it — and how all those fond memories were created and facilitated by adults like Manny and Victor for that exact purpose. They just want to be part of my memory. In one of the film’s most introspective and revealing scenes, we learn that Victor was not allowed to celebrate Halloween as a child. He sat inside, as other children frolicked together outside in costumes trick’r’treating. Victor’s motivations are completely transparent. He doesn’t have those same memories that I do. So now he’s reclaiming a lost childhood by creating memories for newer generations. There is an element of self-absorption there, but the outcome is so sincere and wonderful that Victor’s desperate need to overcome his childhood void is actually rather sweet. He is doing all this for himself, but he is only fulfilled when he is connecting with other people and impacting their lives in happy ways.

The Bariteaus

Whether or not Victor Bariteau is the most interesting subject in the film is debatable, but he is the one that Stephenson is clearly most taken with. Victor’s style of home haunting is a rather seamless follow-up for Stephenson from movie making. Like a passionate filmmaker, Victor is consumed by his vision for his home haunt, and in turn consumes his family and friends. He is a taskmaster, and as Halloween approaches, a bit of a slave-driver. Yet no one ever turns their back on him because they believe in his vision and want to be a part of it. It is fascinating seeing the way that his wife and two daughters indulge Victor, and also indulge their own passions for the project. Victor’s two young daughters don’t even go trick’r’treating, because they have the best show in town to entertain them. I just found it so inspiring seeing these unassuming suburbanites tossing themselves into such a pure form of artistic expression with no goals of fame or fortune — just a love for what they’re doing and desire for recognition from their neighbors. And the whole Bariteau clan is compelling to get to know. The break-out character from The American Scream is Victor’s oldest daughter, Catherine, who most genuinely enjoys helping her father out. We’re introduced to Catherine as she excitedly dumps out a box of mutilated Barby dolls that she created for a previous home haunt, and then tells the camera, “I hate Barbies.” I’m sure right then and there a whole generation of young male horror fans will have found a new crush.

I don’t think it is a spoiler to say that Halloween happens. And the haunts are put on. But fellas, when those little kids come on screen in their costumes, tugging on their parents’ clothes in both terror/anticipation of entering Victor’s haunted house, well, get ready to embarrass yourself in front of your wife or girlfriend when you need to start pretending you have something in your eye. Not everyone I talked to at Fantastic Fest had the same reaction, but most did. Maybe you need to have had a certain kind of childhood. I don’t know. But I know that writers for Fangoria, ShockTilYouDrop, Badass Digest, FEARnet, Bloody Disgusting, and yours truly, all cried like total pussies seeing those kids shrieking in happy horror. So there you have it. You’ve been warned.

The scariest thing you do this Halloween week may be facing your own heart-warming childhood memories! Mwah ha ha ha ha!

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars