It’s pretty clear from the early going that Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master will not be the film you were expecting. This is a work that demands your constant attention as it forces you to abandon any sort of preconceived notions you’ve brought in with you. At a time where theatres are almost entirely devoid of heady, adult material, The Master is a breath of fresh air – even if it doesn’t come easily. Not as emotionally resonate as Boogie Nights and without the fantastical backdrop of There Will Be Blood; The Master still stands as one of best films of 2012 – and absolutely the year’s most thought-provoking submission thus far.

It’s pretty clear from the early going that Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master will not be the film you were expecting. This is a work that demands your constant attention as it forces you to abandon any sort of preconceived notions you’ve brought in with you. At a time where theatres are almost entirely devoid of heady, adult material, The Master is a breath of fresh air – even if it doesn’t come easily. Not as emotionally resonate as Boogie Nights and without the fantastical backdrop of There Will Be Blood; The Master still stands as one of best films of 2012 – and absolutely the year’s most thought-provoking submission thus far.

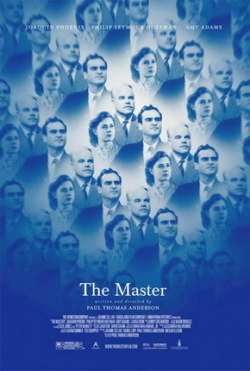

As soon as you hear Paul Thomas Anderson is directing a work that employs L. Ron Hubbard and Scientology as thinly-veiled framing devices, you start conjuring up ideas of what the film could have been. At least I did. I went in fully expecting a film that saw Joaquin Phoenix’s Freddie Quell indoctrinated at the hands of a sinisterly persuasive Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman) and his movement, referred to here as The Cause. Yet The Master is not that film. If anything, it’s about the futilities of an attempted indoctrination. In Freddie, Lancaster sees both a challenge and potential companion. In his repeated attempts to draw Quell into his world, the opposite occurs. Freddie becomes the liability that Dodd can’t seem to shake – even at the behest of his followers.

Freddie arrives to The Cause a drifter. Aimless, alcoholic and without any compelling worldview driving him outside of unsuccessful attempts bedding women. In truth, The Master might be the most complicated and intellectually stimulating film that’s ever chronicled one broken man’s quest for pussy. From the moment we meet Quell, his peculiarities and motivations are readily apparent. His tenure in a post-WWII Navy is at an end. Crass and perverted, we see Freddie cradling a monument of the female form erected from sand. In the next frame, he’s furiously jerking off into the ocean.

When the drifter finds himself on The Cause’s boat (a structure lifted from Scientology’s ocean-faring Sea Org) he’s immediately embraced as a new recruit. This relationship between two eccentric men is the crux of The Master – a philosophical give and take between two nutters with misguided philosophies. Their commonalities seems to be a shared habit of objectification and a fondness for the drink. Where Quell objectifies women, Dodd objectifies human emotion – bending and twisting peoples’ insecurities into his own self-fulfilling worldview.

The interplay between these strange and provocative men makes for a compelling watch. That you’re regularly questioning what you’re watching and why makes the experience all the more fulfilling. This is a film where a knowing glance or a brief exchange are more than typical “point A to point B” exposition. Anderson uses his script to meditate on some very adult subject matter – unleashing at a film that is open to a variety of reads and interpretations.

Phoenix is unrecognizable as Quell. Childish and without the benefit of self-editing, Freddie is the sort of damaged that seems like he’d be a perfect candidate for The Cause. But we’re quick to see he’s anything but, as Dodd has clearly mistaken deep-rooted mental illness for malleability. In a week where we’ve seen a former Scientology member brutally murder his helpless landlord, it becomes clear how unprepared an organization like The Cause is to handle a lost soul like Freddie. Cults are essentially a numbers game that takes advantage of the hearts and minds of their followers. The difficulty they encounter in Freddie exposes organizations like it for how ineffective they truly are. And it’s all a crumbling facade around Phoenix’ brilliant performance. Every gesture, every inaudible line of Quell’s mumbling, all serve to make you forgot about the actor’s misguided turn in I’m Still Here. The real tragedy of that project is evidenced in The Master, as we’re reminded that one of the most gifted actors of our time had been distracted by lesser work for the better part of two years. This, the highest level of thoughtful and artistically compelling cinema, is exactly where an actor of Phoenix’ calibre belongs.

In addition to Phoenix’ return to form, it should come as no surprise Phillip Seymour Hoffman delivers his ever-reliable work. He’s culling from Hubbard of course, but his charisma and gravitas owe themselves in part to other staunch figures of history – as shades of Orson Welles and Hunter S. Thompson also feel present in his performance. Amy Adams is effectively creepy in the buttoned down role of Dodd’s wife, Peggy. And Laura Dern makes a surprising appearance as Helen, a devout follower of The Cause who shares a really intense scene with Hoffman.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s script provides no easy answers. And Radiohead’s Johnny Greenwood delivers a score as bizarre and unsettling as his work in There Will Be Blood. The best compliment I can bestow unto The Master is that, a week after seeing it, I’m still thinking about it. This isn’t the sort of film you either love or hate. It’s the sort of film you discuss – a characteristic lost on most modern cinema and mainstream filmmakers. PTA’s The Master isn’t my favorite of his works, but it might someday prove to be his most intellectually rewarding.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars