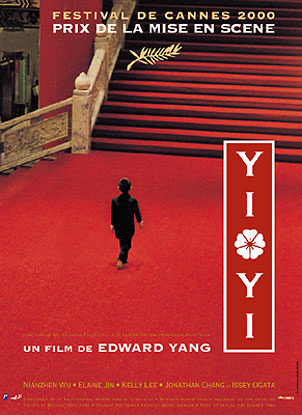

When I first experienced the cinema of Edward Yang (at New York City’s cramped Cinema Village) in late 2000, I had no idea I was also witnessing its culmination. How could I? Yang’s works were rarely screened in the United States and never properly distributed; he was an unknown quantity to anyone outside of the festival circuit. Indeed, it wasn’t until Yang won the Best Director prize at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival that I began to regard him as something more than "the Taiwanese critical darling not named Hou Hsiao-hsien" – and this was hardly a favorable association, as Flowers of Shanghai, the one Hsiao-hisen picture I’d seen up to that point, had both baffled and bored. In other words, sitting through a three-hour Taiwanese epic described in the program of the New York Film Festival as "a masterpiece of synchronicity, empathy and narrative control" was not high on my list of ways to escape the agony of a day job that was, in its way, a masterpiece of panic, languor and punishing stupidity.

When I first experienced the cinema of Edward Yang (at New York City’s cramped Cinema Village) in late 2000, I had no idea I was also witnessing its culmination. How could I? Yang’s works were rarely screened in the United States and never properly distributed; he was an unknown quantity to anyone outside of the festival circuit. Indeed, it wasn’t until Yang won the Best Director prize at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival that I began to regard him as something more than "the Taiwanese critical darling not named Hou Hsiao-hsien" – and this was hardly a favorable association, as Flowers of Shanghai, the one Hsiao-hisen picture I’d seen up to that point, had both baffled and bored. In other words, sitting through a three-hour Taiwanese epic described in the program of the New York Film Festival as "a masterpiece of synchronicity, empathy and narrative control" was not high on my list of ways to escape the agony of a day job that was, in its way, a masterpiece of panic, languor and punishing stupidity.

What a surprise, then, to find that Yi Yi was not obsessed with the quotidian or impressed with its own restraint to the point of aesthetic listlessness. Though the film was definitely immersed in the day-to-day drudgery of family life, I was astounded at the way Yang’s exacting compositions consistently placed his miserable, spiritually marooned characters in and against the bustling rest of the world. I’d never seen anything like it! Yi Yi was rigorously structured and emotionally sprawling at the same time. Who knew the styles of Michelangelo Antonioni and James L. Brooks were so compatible?

The miracle of Yi Yi is that it evokes the full range of human emotion without ever once feeling manipulative; the material itself could very easily go maudlin in the hands of even a great filmmaker, but Yang calmly guides the picture as if it was always meant to be. There is something shockingly right about Yi Yi. It is one of those rare films that is for everyone; critics can deconstruct it for days while casual viewers can just sit back and enjoy a complex narrative that isn’t at all confounding or esoteric. And yet Yi Yi is still largely unseen in this country. Though The Criterion Collection reintroduced it to American audiences last year with a superb DVD, it is routinely avoided as if it were… well, a Hou Hsiao-hsien movie. I can handle Hsiao-hsien’s work being marketed to a double-figure viewership. And I can understand, though not approve of, Tsai Ming-liang’s inability to break out of the festival circuit. But if Yi Yi is representative of Yang’s cinema in general, it makes little sense to me that a man with such a Western sensibility should be relegated to the art house.

And so it will be with a heavy heart that we continue to lobby for the U.S. release of his prior works, knowing that there will be no more: Edward Yang succumbed to cancer on June 30th at the age of fifty-nine. Though it had been seven years since Yi Yi, there was always the hint of The Wind, an animated Jackie Chan vehicle(!), to keep us hopeful that Yang hadn’t exhausted his greatness or lost his vigor for the medium. Whether it was his sickness or a lack of financial support that kept him from following up the greatest film of this decade, none of that matters now. The most fitting tribute to the life and art of Edward Yang is to share Yi Yi with everyone you know. The whole world is in it.