The Crop: Righteous Kill

The Crop: Righteous Kill

The Production Company: Millennium Films

The Director: Jon Avnet

The Writer: Russell Gewirtz

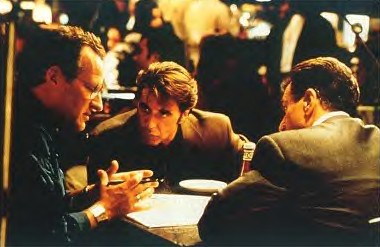

The Actors: Robert De Niro and Al Pacino

The Premise: Two New York City detectives hunt a morally indignant serial killer steadily knocking off perps with whom the officers have a history.

The Context: Much as we all all love Heat (and we all love Heat), it’d be a horrible, hateful lie to suggest that ten minutes of shared screen time* completely scratched our De Niro/Pacino itch. Though the electrifying Kate Mantilini-set sequence in Michael Mann’s 1995 existential crime epic certainly delivered on its pre-release hype, it’s not like we want the guys to avoid each other for the rest of their careers. If it’s a case of "always leave ’em wanting more", well, we’ll never get what we really wanted, which was to see them square off in their prime, so what’s the harm in bringing them together at least one more time? And in a movie where they’ll play opposite each other for most of the running time rather than doing the cat-and-mouse thing from a distance?

The most obvious way to accomplish this is to have De Niro and Pacino play cops, preferably partners (though not Partners). While we’re running ideal scenarios, it would be especially wonderful to pair them in a police corruption drama with Sidney Lumet, though, all due respect to the soon-to-be eighty-seven-year old filmmaker, he hasn’t seen his prime since 1990’s Q&A. Still, there are plenty of incredible directors out there who’d sign away their soul at the crossroads (i.e. The Grill) to have De Niro and Pacino padding around on their set. Shit, why even qualify that: every director living today – save for those who do not occupy our version of reality, like David Lynch, Crispin Glover and Uwe Boll – would die to roll film on these two at the same time.

So, naturally, the honor of getting Michael Mann’s sloppy seconds went to… Jon Avnet?

Please don’t take this as disrespect. I like Jon Avnet quite a bit. Every time I’ve interviewed him, he’s graciously humored my frantic entreaties to get his pal Paul Brickman back behind the camera (there’s another guy I’d love to see directing these two heavyweights). But while I can take nothing away from him as a producer, I don’t know that I can give him a whole lot of credit as a director. What’s Jon Avnet’s best movie? Fried Green Tomatoes? I ask because, aside from The War, it’s the only film of his I’ve seen (though I’ve happened across Up Close and Personal on cable, and once stuck with it for a whole five minutes!). If only inexperience and lack of artistic ambition were Avnet’s chief detriments as a director; he’s also on the hook for Al Pacino’s only direct-to-DVD movie, 88 Minutes (now that’s an inauspicious title).

Why is he getting the privilege of working with De Niro and Pacino again? Russell Gewirtz’s screenplay must just be all kinds of director-proof.

The Script: Considering the quality of Gewirtz’s first produced script, Inside Man, this isn’t necessarily a stretch. Though a tad convoluted for some tastes, I thought Inside Man was ingeniously plotted, impeccably structured and rich with wise-ass New York City dialogue. It was a hell of a debut, and established Gewirtz as a writer to watch.

Well, consider him watched and read, and consider me mildly disappointed, because Gewirtz has fallen in love with narrative gimmickry; essentially, the entirety of Righteous Kill relies on the reader/viewer only knowing the two main characters by their nicknames. I’m all for misdirection and withholding information to trick the audience, but Gewirtz is so preoccupied with this kind of sub-Shyamalan gamesmanship that his characters wind up being nothing more than chess pieces. De Niro and Pacino may be two of the best to ever live, but even they can get lost in a story that’s too clever for its own good.

The screenplay opens with the burial of David Fisk, a decorated New York City detective who, as the priest says at his graveside service, embodied "the expression ‘New York’s Finest’" (for the first time in recorded history, the character is quoting David Dinkins favorably). Surviving him is his partner, Detective First Grade Thomas Cowan, though – and this is important – we never see which is Cowan and which is Fisk!!!

Cut to a conference room, where two Internal Affairs investigators are watching the videotaped confession of "Turk", who identifies himself as "David Fisk, Detective Second Grade". The two IA officers are stunned as they listen to Turk/Fisk recount his fourteen on-the-job slayings, only three of which were classified as "righteous shoots"; the others were murder, or, as Fisk spins it, executions of "criminals and scumbags that didn’t deserve to live".

Flashback to, um, happier times: Turk ambushes a young woman in her apartment and proceeds to ravish her. But before you can say, "Bad, bad Lieutenant!", we find out that the sex is consensual; the young woman in question, Karen, is an officer herself, and rather enjoys rape role play (as did my grandmother – though her idea of rape was my grandfather changing the channel during The Lawrence Welk Show). With the necessary damage done to Turk’s character, Gewirtz introduces us to the detective’s partner, Rooster, as the two attempt to one-up each other at the firing range (we learn that Fisk is the better shooter, though – and I can’t stress enough how important this is – we never find out which one is Fisk!!!). The detectives are then called out to the field to investigate the murder of a pimp named Rambo, whose killer left a calling card of sorts in a poem that reads:

"He trades in sin, distributes flesh.

He picks the fruit when it is fresh.

Now someone else must slap his whore.

His heart has stopped, he breathes no more."

As the detectives begin to dig into this case (and after they get a collar killed while trying to bust a major Harlem coke dealer – a bit of action which distends the first act quite a bit), they discover that all of the victims are connected to them in one way or another. That the partners volunteer to take the point in this investigation and send their colleagues chasing down woefully false leads only rouses further suspicion; eventually, as the bodies keep piling up, Turk becomes the prime suspect.

But what of Rooster? Well, that’s one of the script’s biggest problems: unless Gewirtz plans to bring in a late second-act ringer, you’ve got two potential culprits. And it soon becomes clear who is the guilty party. Unfortunately, Gewirtz thinks he’s written Murder on the Orient Express, and dedicates the final fourteen pages to flashbacks showing off his narrative trickery. This is a sensationally bad idea because each complication/twist has only two possible outcomes: imagine how The Usual Suspects would’ve played had McQuarrie limited the team to Gabriel Byrne and Kevin Spacey; that should give you an idea of how thuddingly obvious this all is.

Why It Should Be Good: Gewirtz is aces at dialogue, and I’ve heard tell that De Niro and Pacino aren’t exactly slouches when it comes to wiseguy banter.

What It Might Suck: Aside from Gewirtz’s frustratingly pat plotting, there’s this: Turk and Rooster are written as thirty-nine and forty-one. Generally, when it comes to cop movies, knocking the ages up ten or fifteen years isn’t a big deal; the problem with Righteous Kill, however, is that the dilemma faced by Turk and Rooster is age specific. Both De Niro and Pacino are well into their sixties (hell, Pacino will be seventy in three years); cops that long in the tooth have already made peace with the ubiquitousness of evil, which means they’re either drunks or retired. With some judicious rewriting, this would’ve been a perfect screenplay for De Niro and Pacino in the 1980s. Signing on to it now smacks of wishful thinking. There’s got to be better material out there for these two legends.

What I’ll Be Rambling About Next: Looks like The Winter of Frankie Machine! But don’t give up on that Chan Wook Park movie; it’s just gestating longer than expected.

*I’ll qualify that as "give or take" for the obsessive who posts to our message boards the precise amount of screen time down to the tenth-second.