If there is any justice on this whirling glob of dirt and water, there will be a major rediscovery of Daryl Dukes’s Payday, in which world-class hellraiser Rip Torn gives the performance of his career as country-and-western warbler Maury Dann. Currently unavailable on DVD, and written by a now deceased novelist, Don Carpenter, whose entire oeuvre appears to be out-of-print, Payday is the epitome of an overlooked classic (memo to Roger Ebert: you gave the movie four stars in 1975; maybe this could make next year’s Overlooked Fest lineup). It’s aimless and ambiguous and authentic in ways most films are afraid to be nowadays; for those of us baptized in the rigid structure of storytelling (thanks, Star Wars!), it’s constantly surprising and never dull, a perfect reflection of life on the road with a bastard like Maury Dann.

If there is any justice on this whirling glob of dirt and water, there will be a major rediscovery of Daryl Dukes’s Payday, in which world-class hellraiser Rip Torn gives the performance of his career as country-and-western warbler Maury Dann. Currently unavailable on DVD, and written by a now deceased novelist, Don Carpenter, whose entire oeuvre appears to be out-of-print, Payday is the epitome of an overlooked classic (memo to Roger Ebert: you gave the movie four stars in 1975; maybe this could make next year’s Overlooked Fest lineup). It’s aimless and ambiguous and authentic in ways most films are afraid to be nowadays; for those of us baptized in the rigid structure of storytelling (thanks, Star Wars!), it’s constantly surprising and never dull, a perfect reflection of life on the road with a bastard like Maury Dann.

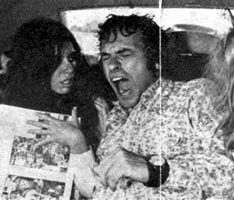

Whomever Carpenter patterned Dann after, I hope for our sake that he’s either settled down or made peace with his maker. One of the great things about Payday, which is basically two enormously eventful days in the life of the performer, is that Duke, Carpenter and Torn never deign to portray the character in a redemptive light. If there’s anything wrong with the hard-drinkin’, hard-boozin’, hard-fuckin’ life Dann is leading, he’d just as soon sock you in the mouth as hear about it. We get a perfect, scuzzy illustration of Dann’s low character early in Payday when he celebrates a successful nightclub gig by luring an admirer’s date out to the parking lot for a clumsily coerced quickie in the backseat of his Cadillac. The women in Dann’s life are interesting in this regard; though they definitely want to sleep with him, they’re completely taken aback by his brusque manner of seduction (which, in this case, amounts to opening the door of a car and indicating "Get in!"). If you’re desperate to find something respectable about Dann’s character, there’s this: he isn’t one for false pretenses. If you ride with Dann, he’s aboveboard about the fact that you’re going to get fucked. (For the bulk of the film, he keeps two women with him in Cadillac: the new girlfriend/groupie and the one on the way out.)

If you’re a woman, that is. If you’re a fella, you’re subject to a whole host of indignities: at any given moment, Dann might take a poke at you, steal your woman, rouse you at an ungodly hour to go shoot some birds, ask you to take the rap for his law-abusin’ ways and/or fire you from the band. To hurtle about in Dann’s orbit is to live dangerously. After a while, we begin to understand that Dann’s mercurial personality is the reason he’s not a huge star; people talk him up as the next Johnny Cash, but Dann is too unstable to play the game long enough or smart enough to take that next step. When a rural radio deejay – who’s been wearing out Dann’s latest single – prods the singer to make an appearance at a local charity event, Dann flatly refuses to play quid pro quo.

Think of Gary Cole’s incorrigible father figure in Talladega Nights played completely straight, and you’ve got a pretty accurate picture of Maury Dann. There’s a fantastic scene midway through the film where Dann stops by his ex-wife’s house bearing birthday presents for one of his kids; the problem is, Dann’s not even close to the actual date (and he doesn’t even seem clear on who’s birthday it is in the first place). An argument ensues, which is punctuated by Dann hauling off and striking his ex. There’s a long, anguished beat. Dann quietly takes a seat on a hideously designed couch in a hideously decorated living room as the freshly-slapped woman exits the frame. Finally, she timidly reenters and begins to apologize for Dann. It’s classic abused spouse behavior. But if you think Dann’s going to finish the apology and move on, you’ve got the wrong fuckin’ movie; Dann just stands up, barks his lack of contrition, and Duke abruptly transitions to the next scene.

And this is only the second most humiliating moment in Payday. First place goes to a hilariously protracted sequence on a country road as Dann finally decides to sever ties with one of his backseat female companions. If I were to describe it, you’d probably think I was as big a bastard as Dann for finding it funny, but Duke stages the bit with such exquisite comedic timing that you’ve no choice but to bust out laughing. That’s how Duke eases you past some truly objectionable acts; though the film does visit some very dark places (e.g. a trip to the rundown house of Dann’s pill-addicted mother who looks twenty-years older than she should), the outrageousness of the singer’s behavior is just too much. I mean, how else are you supposed to react to a guy who merrily holds court at a post-gig hotel party while sitting on the shitter? Payday is full of casually shocking sights like that. And every scene crackles because you have no idea what to expect from Duke, Carpenter or Torn.

If Payday has a reputation, it’s as the movie that should’ve established Torn as one of his generation’s best actors. But the picture – the debut production for Saul Zaentz’s Fantasy Films – never received a wide release, and has since been buried due to a lack of availability and the fact that Torn subsequently went the character actor route. Watching the actor bare-knuckle his way through Payday is to wonder what might’ve been. Though his own erratic behavior probably would’ve kept him from a steady run as a leading man (please Google "Rip Torn" and "Norman Mailer"), there’s no doubt that he was the genuine article – a wilder, scarier, more unpredictable Jack Nicholson. As many have noted, Torn was a man seemingly consumed with violence; when he erupts onscreen, you’re witness to a temporary exorcising of personal demons. He touches depths to which few actors are privy.

For Duke, a director who toiled mostly in television, Payday would be a career peak (that said, I have recently heard good things about the Curtis Hanson-scripted The Silent Partner). Though The Thorn Birds and Tai Pan loom embarrassingly large on his resumé, Duke was ill-suited to these bloated best-seller adaptations; he was a director in love with atmosphere and people, and Payday is as textured a character study as the 1970s yielded. It’s a shame that he won’t be around to experience the inevitable resurrection of this forgotten classic (Duke passed away in October of 2006) – and, sadly, neither will Carpenter, who committed suicide in 1995.

Hopefully, we can persuade Warner Home Entertainment to release Payday to DVD very soon. For now, you can order a used copy of the VHS through Amazon.

(Much dap to my boy Kevin Biegel for screening this last Friday as the first of what better be an ongoing series of forgotten classics. I wouldn’t have sought Payday out on my own.)