Somewhere in an immaculate kitchen in an immaculate house situated in an immaculate neighborhood somewhere in Bel Air, Nora Ephron is toasting her troubles away*, wondering how in the hell a common vulgarian like Judd Apatow could reinvent the romantic comedy for modern audiences. And somewhere, perhaps a few blocks away or maybe in an adjacent living room, Nancy Meyers is on her fifth glass of chardonnay wondering the exact same thing.

Somewhere in an immaculate kitchen in an immaculate house situated in an immaculate neighborhood somewhere in Bel Air, Nora Ephron is toasting her troubles away*, wondering how in the hell a common vulgarian like Judd Apatow could reinvent the romantic comedy for modern audiences. And somewhere, perhaps a few blocks away or maybe in an adjacent living room, Nancy Meyers is on her fifth glass of chardonnay wondering the exact same thing.

The answer is simple: Apatow is writing from what he knows, and what he knows is the vicissitudes of romance, the pain of growing up a little nerdy and, frankly, life as it is lived outside the cocktail circuits of New York City, Washington D.C. and Hollywood. He isn’t concerned with meeting some kind of bullshit standard imposed by Harper’s Bazaar and Architectural Digest; he’s just trying to maintain his sanity and make sure his wife doesn’t leave him and his and kids don’t hate his guts in twenty years.

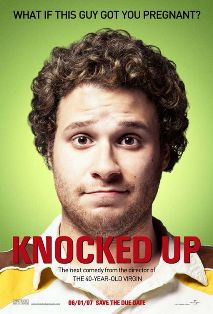

Since it’s almost impossible to manage a successful Hollywood career and be happily married, Apatow has endeavored to conflate his professional and personal lives by casting his family in Knocked Up, a shambling depiction of one shlub’s unexpected journey from suspended, wake-and-bake adolescence to something resembling adulthood. In it, Apatow has two surrogates: Ben (Seth Rogen), a twentysomething stoner with dubious aspirations (he’s developing a website that pinpoints female nude scenes in movies), and Pete (Paul Rudd), a semi-contented husband and parent who may be leading a double life. Through these two characters, and the multitude of goofballs in their respective orbits, Apatow composes a rambunctious, heartfelt fantasia on adult life in the twenty-first century. But, unlike Ephron and Meyers, he also evinces a genuine, non-adversarial interest in the other sex, which is why Katherine Heigl (as Alison, the woman Ben inadvertently impregnates during a drunken one-night stand) and Leslie Mann (as Debbie, Pete’s loving but suspicious and subtly acerbic wife) end up giving the most sympathetic performances in the film.

This is what’s so fascinating about Apatow’s art; he’s a lewd and crude humanist who acknowledges that the male dream of a twenty-four hour party and a different woman every other night or month or year (depending on your game and attractiveness) must come to an end. To be entirely accurate, his movies are half-sex comedy and half-romantic comedy; he allows us to enjoy the bacchanalian camaraderie for a while, but then he hits us with the bill. And it’s huge. No man can sustain this lifestyle; hell, even Warren Beatty, the ultimate playboy, eventually surrendered to marriage and fatherhood.

That’s why some might complain that the air goes out of Knocked Up during its transition into the third act. This is a fair criticism, but it’s basically a reaction to the abrupt (and, in this era, unnatural) death of Ben’s twenties; that whole marriage and parenting nonsense is something to put off until one’s thirties or forties. As we watch Ben try to have it both ways (i.e. being attentive to the needs of his pregnant partner while still having a good time where he can find it), those of us in our thirties begin to wonder a) how we might’ve handled the same situation at his age, and b) when or if we’re going to subject ourselves to this fresh hell. Though Apatow keeps the jokes coming as Ben begins to fail Alison, it’s hard to laugh because he’s being such a selfish prick. And, sadly, we’d probably behave in much the same way if confronted with his conundrum.

This is where Apatow’s women rescue the movie and their men. Though they’re difficult and demanding and, well, women, they’re also completely right; Ben is withdrawing from Alison out of fear and Pete is trying to preserve some small patch of his freedom, which is unfair to Debbie (even if it’s something as innocuous as a fantasy baseball league). It’s strange to see a student of early Harold Ramis come down on the side of the ladies, but Apatow is also a protégé of Garry Shandling; he’s got that ugly honesty trait that makes you wince through your laughter at times**. And he’s also a decent enough guy to know that the women in his life (Mann and his daughters, Iris and Maude) deserve his best.

Apatow bravely leaves open the possibility that Ben’s best may not be enough to keep his relationship with Alison afloat, but the effort is what counts. Ben might not be ready or right for this woman, but he’s at least moved out of the flophouse he shared with his drinking/drugging budies in order to be a responsible part of his child’s life. It’s a touching gesture, and it’s the right one, too. Though some may instinctively deride Ben’s capitulation as conservative (just as some might view Andy waiting for marriage to lose his virginity in The 40-Year-Old Virgin as awfully old-fashioned), it’s the only choice a good man could make. While this might be an idealized scenario (if I ever slip one past the goalie, I hope it’s on a girl as beautiful and as grounded as Alison), it’s also a commendable one; Ben’s no hero, but he is the upstanding kind of guy we’d like to be. Apatow believes (as per Paul Feig via George Bernard Shaw) that all men mean well. And we do, though we often get sidetracked. But if you give us time, and nag us an appropriate amount, we’ll find our way back to our noble nature.

I swear, give Apatow enough time and enough movies, and he just might save the world.

*I did a profile on Ephron for Creative Screenwriting, and she spoke at length about her love for bread. I thought nothing of it until I saw Bewitched, and, sure enough, there’s a scene in some fashionable Los Angeles eatery where you can toast bread at your table. At this point, I thought back to Heartburn and realized Ephron’s just nutty about food in general, but this bread business is apparently all-consuming. Truth be told, I’d much rather have Ephron designing high-end breadmakers than churning out high-priced studio flops.

**Shandling also took an admirable swing at the pain of parenthood in the very smart, unjustly maligned What Planet Are You From?