The trouble with the Shrek movies is that their admirable message of self-acceptance is drowned in a deluge of pointed pop culture references that’s essentially the result of one rich white guy (former Disney CEO Michael Eisner) snubbing another rich white guy (Jeffrey Katzenberg, former heir to Eisner’s throne and now the "K" in Dreamworks SKG). They may look like children’s movies, play like children’s movies and fart with impunity like children’s movies abundantly do nowadays, but they are, at their collective heart, acts of corporate score-settling. And while based on a beloved children’s book by William Steig which skewered fairy tale conventions, the tenor of the gags in Dreamworks Animation’s CG offshoots, most of which target Disney in one way or another, aren’t good natured; they’re spiteful.

The trouble with the Shrek movies is that their admirable message of self-acceptance is drowned in a deluge of pointed pop culture references that’s essentially the result of one rich white guy (former Disney CEO Michael Eisner) snubbing another rich white guy (Jeffrey Katzenberg, former heir to Eisner’s throne and now the "K" in Dreamworks SKG). They may look like children’s movies, play like children’s movies and fart with impunity like children’s movies abundantly do nowadays, but they are, at their collective heart, acts of corporate score-settling. And while based on a beloved children’s book by William Steig which skewered fairy tale conventions, the tenor of the gags in Dreamworks Animation’s CG offshoots, most of which target Disney in one way or another, aren’t good natured; they’re spiteful.

Obviously, you can’t expect children to pick up on these subtleties, so their love for these soulless exercises in cynical franchise making can be excused. And most parents deserve a pass, too, because denying their kids access to glossy, aggressively marketed product is the first step down the path to eventually screaming "Turn it off!" in a dingy porn theater. But critics should know better. When they praised the first Shrek for subverting "the well-worn expectations of its genre" (as Richard Schickel did while declaring it the best film of 2001), someone should’ve sat them down with Jay Ward’s "Fractured Fairy Tales" or any number of Looney Tunes classics, and reminded them it’s all been done much, much better in the past. Once devoid of this alleged novelty, Shrek‘s only noteworthy aspect is the Eisner-Katzenberg subtext.

While that’s all subsided by now, it’s important to recall the climate in which Shrek was released, because it remains the primary reason why the film became a pop cultural phenomenon. Disney was on the ropes in 2001; their decade-long adherence to the musical formula championed by Katzenberg had engendered a rigid set of expectations, so that, when they changed things up with Dinosaur and Atlantis: The Lost Empire, audiences were thrown. Couple that with the studio’s arrogant bullying of competitors vying for a share of the animation marketplace, and critics were ready to see Disney take a tumble.

How else to explain a mediocrity (in animation and content) like Shrek becoming a critical darling and an Academy Award-winner for the inaugural Best Animated Feature Oscar over the far superior Monsters, Inc. (it even earned a competition berth at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival)? Though it’s fair to suggest that the film would’ve attained pop cultural dominion without the deafening roar of accolades, it’s impossible to separate that initial burst of enthusiasm from the Disney v. Dreamworks context. Now that that’s all thankfully settled, we’re more interested in viewing these as supposedly smarter-than-average entertainments. And we’re discovering that they can’t withstand the scrutiny.

After the excessive Shrek 2, which was an exhausting double order of everything that seemingly worked the first time around sans the sporadic comedic invention, Shrek the Third deserves some credit for emphasizing narrative over non-stop gags. Unfortunately, this tact also magnifies the worst aspects of the previous two films: Shrek the Third is one seriously talky piece of children’s entertainment. It’d be one thing if the conversation in question were witty and well-observed, but the screenplay – a stitched-together effort from Chris Miller, Aron Warner, Jeffrey Price, Peter S. Seaman, based on a story by Andrew Adamson – goes heavy on numbingly expository dialogue (an unconscionable sin for such an quintessentially visual medium).

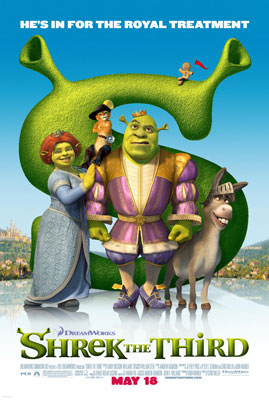

This entry finds Shrek traveling to the far off Worcestershire (with Donkey and Puss-in-Boots) in search of the recently expired King Harold’s young heir, Arthur. When the lad turns out to be a wimp, the future of Far, Far Away looks incredibly uncertain. Exacerbating the troubled state of the kingdom is an assault spearheaded by the jealous Prince Charming, who yearns to fulfill his destiny as foretold by storytelling convention. To accomplish this, he enlists the aid of every fairy tale bad guy in the vicinity, including Captain Hook, Rumplestiltskin and a whole bevy of witches and trolls and whatnot.

With Shrek gone, the pregnant Princess Fiona and her gaggle of entitled gal pals (Snow White, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty and Rapunzel) must defend themselves – though the storybook C-Team, including The Gingerbread Man and Pinocchio, offer up all the resistance they can muster (the surly Gingerbread remains an inspired and endearing character; give him his own movie with a couple of able writers, and this franchise might yet be worth something). This sets the stage for the movie’s primary upending of cliché; when Shrek and company are captured upon their return from Worcestershire, it’s the girls who must save the day.

Once again, the Shrek writers are years behind the curve. Besides, they’ve been playing up the female empowerment angle since the first picture. That this is being promoted as Shrek the Third‘s cleverest gesture is indicative of the franchise’s creative bankruptcy. In fact, after a clever opening shot that turns a brilliant CG sky into a crudely drawn landscape, the movie is a mirthless drag. For Katzenberg, it’s the realization of his worst fears; the signature franchise that toppled his bête noire is now as beholden to formula as Disney’s late 1990s output. For now, he’ll find comfort in the box office returns (and Shrek the Third, despite its crappiness, will be a massive hit), but this is the way to obsolescence. It’s a pain to be the king.