The small moral choices are the ones that fascinate me the most, because they’re the ones we all make. We don’t spend our time worrying about robbing a bank or murdering a spouse, but we do think about picking up that ten you saw fall from someone’s wallet or cheating on your wife just this one time. At the heart of Jindabyne is a moral choice that’s a little larger than the ones we make every day, but one that is a reflection of many of the choices that face us: do we get involved or do we go about our business?

The small moral choices are the ones that fascinate me the most, because they’re the ones we all make. We don’t spend our time worrying about robbing a bank or murdering a spouse, but we do think about picking up that ten you saw fall from someone’s wallet or cheating on your wife just this one time. At the heart of Jindabyne is a moral choice that’s a little larger than the ones we make every day, but one that is a reflection of many of the choices that face us: do we get involved or do we go about our business?

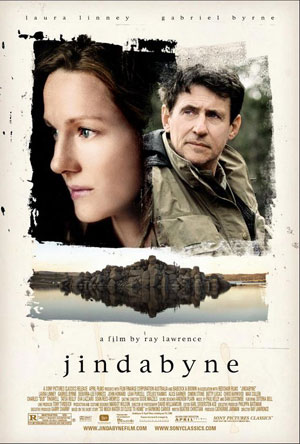

Gabriel Byrne slowly smolders as a man living in the small Australian town of Jindabyne. A former race car driver in Ireland, he now owns a gas station and lives with his American wife and their son. He has a group of friends, men who like to bond over fishing expeditions to a river hidden deep in a barely accessible valley. It’s a ritual that they hold dear, an annual event that makes the rest of the days bearable and make sense. But on this trip they find something unexpected: the naked corpse of an Aboriginal girl floating in the river. They are faced with a decision – hike back to the car and drive hours home to report the body or spend their precious few days on that river. It’s not a choice they exactly make consciously; it’s late when they find the body and they must wait until the next day to hike back. But when morning comes the fish are biting and they slowly put the dead girl out of their minds.

When they return home and finally report the body, the town recoils in horror at how these men could be so callous, and the girl’s family sees undercurrents of racism in how they dealt with the situation. Byrne’s wife, played with gut-wrenching intensity by Laura Linney, decides that there’s needs to be some kind of healing, and tries to bring her husband together with the family of the girl. He’s not sure what he did wrong, though, plus there’s a dark secret in their past that he can’t quite get over, and the fault lines in

their relationship begin to open up.

In many ways that small synopsis is filled with spoilers, as Jindabyne is a movie that takes a Raymond Carver short story, So Much Water So Close to Home, and stretches it across two hours. The story has previously been adapted as one of the tales in Robert Altman’s Short Cuts, but here writer Beatrix Christian and director Ray Lawrence have taken the morsel of what Carver wrote and turned it into a feast. Carver’s one of my favorite writers because he can create entire universes in just a few words; So Much Water So Close to Home may be less than 2500 words, but Carver makes everything come alive perfectly, and Lawrence and Christian have found their way into that expanded Carver world and brought it to the screen.

The movie is, without a doubt, somber. It’s also gorgeous. The hidden river and the mountains around Jindabyne are allowed as many glamour shots as any starlet, and we’re treated to long, sumptuous shots of mountains caressing the green trees on the sides of the peaks. Jindabyne itself serves as a metaphor for the story; the town was once a mile over, but a dam project forced everyone to move. Now there’s a lake and beneath that lake is a dead town that occasionally spits out remnants of itself on fishing hooks. There’s a whole other world beneath the surface, just as there are whole other movies beneath the surface of each of these characters. The film doesn’t lead us through their lives and histories, but pieces of them occasionally surface, suddenly lending new meaning to an earlier scene.

Jindabyne is slow, or maybe more accurately deliberate. The film has things it wants to think about – safety and society, guilt and forgiveness – but it isn’t always interested in speaking about them. These concepts are here for you to consider, to chew on as the camera cranes up to a perfect blue sky beneath which fallible and selfish people stumble and err and just try to be decent.