Welcome back, everyone.

Welcome back, everyone.

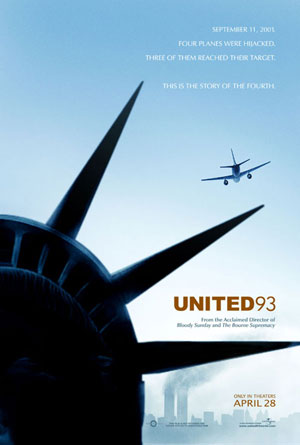

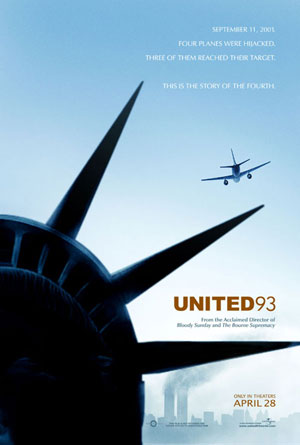

This edition of The Chewer Column comes courtesy of a great group of intelligent and insightful CHUD readers who have agreed to participate in a roundtable discussion dealing directly with the events of 9/11, its place in modern film, and most specifically, the arguments for and against the upcoming United 93.

So without further ado…

Film & 9/11: Paul Greengrass’ United 93

By John Carroll, Alan Cerny, Greg Clark, Hellboy, Brendan Leonard, Jeremy Slater, Dan Whitehead, and YT

George: The field is open to discuss anything and everything United 93

George: The field is open to discuss anything and everything United 93

related, 9/11 in general, and cinema’s overall place in all of this. I

understand John Carroll has already seen the film, so any shareable

details from him would be good. Also, Devin’s coverage has already

begun, and I know any and all of that would be good fodder for

discussion here as well.

So, let me start with perhaps a rather simple series of questions, but hopefully ones that’ll help get the ball rolling:

Film

is a manipulative medium by the very nature of its individual

components… editing, scoring, etc. An event such as the hijacking of

an airliner has been depicted in film before, but in this case, being

that it’s about 9/11, do you think perhaps a dramatization within

narrative filmmaking is a good approach to objectively show audiences

what may or may not have happened aboard the United 93 flight? Can it

be objective? If not, if it’s subjective, and if it’s always going to

be manipulative in some way, is that even a bad thing? What positives

can come from such a depiction? What negatives?

Jeremy Slater: I guess I’ll be the annoying contrarian to get things rolling.

I’m

certainly not opposed to the project from an emotional standpoint, and

I think the cries of “Too soon!” are short-sighted. Films like this

*need* to be created while the wounds are still fresh and raw. Waiting

for the passage of time to dull the pain is how you wind up with Pearl Harbor,

where a tragedy devastating enough to radically alter the beliefs and

foreign policies of an entire nation somehow becomes co-opted into

something brainless and horrible where the Underworld girl fucks Lucky Number Slevin on a pile of parachutes. I don’t want to subject everyone’s grandkids to a similar fate in 2039.

This

doesn’t mean making the story of Flight 93 into a film is a

particularly good idea, though. My central problem with the premise is

what I would describe as The Perfect Storm

effect. Namely, when you’re telling a true-life story where none of the

leads survive, you’re forced to improvise reality. So you throw in a

shark. You nearly drown John C. Reilly. And the problem is that

everybody in the audience–or at least the educated viewers, the ones

who will probably make up United 93’s

core audience–are constantly and acutely aware that they’re watching

actors playing very real people doing very imaginary things in the

moments before their very real deaths.

And it’s a problem that’s compounded when you involve the families and communities affected by the incident. To continue with The Perfect Storm

analogy–because I don’t feel as guilty picking on dead fishermen–the

possibility for bias and canonizing the dead often wins out over the

need for emotional and intellectual honesty. Perhaps the crew of the

Andrea Gail really was a wacky and noble group of fishermen who loved

each other like brothers and rarely swore and treated their families

like angels. Perhaps Clooney’s character really did drown with a pithy

one-liner fresh on his lips instead of miserably shrieking for his life.

Or perhaps films like United 93,

even when created by talented filmmakers with the best of intentions,

can never really serve as anything more than wish fulfillment, the way

we hope things went down. You know the old saying…if it’s not true, it

oughtta be. But you’re still straddling the line between biopic and

fanfic, and that’s a damn dangerous place to be.

YT:

YT:

Well, to address your earlier question and further to what Slater said,

I don’t believe it’s possible for this film to be objective. Everyone

will have made a subjective contribution to the tapestry, knowingly or

unknowingly, as Slater noted.

My

contribution to the "it’s too soon" chorus is that I believe it IS too

soon. The whole story has not yet come out about virtually every aspect

of 9/11. What happens to the movie if some day a fighter pilot comes

out of the woodwork on his death bed and says, "I shot that plane down

on Cheney’s order." What happens if evidence reveals itself that

directly contradicts what some of the people on cell phones said?

Obviously I can’t speak for the families of those who died on Flight

93, or even anyone who witnessed firsthand the destruction of 9/11, but

I did watch it on live TV, and it definitely changed me as it changed

everyone who saw it happen live. Knowing that, knowing what came after,

knowing what it changed and how it changed it, all contribute to my

feeling that the pure unvarnished truth needs to come out about 9/11,

no matter how thorny. Telling the story piecemeal, through

patched-together, sincere yet incomplete sources, when wounds are still

raw and the mystery remains largely unsolved, seems misguided to me.

That

said, I appreciate that Paul Greengrass approached this film with

utmost integrity, scruples and purity of intent. Everything I’ve read

about it leads me to believe it goes into exacting detail to the

fullest extent possible and was made with the full cooperation and

input of the families. That’s to be totally applauded. I also know he’s

a talented and accomplished filmmaker, so I’m sure it’ll be well made.

But that’s the "how." I don’t know if he has a strong enough "why," at

least for me to want to see it. If there were new information he were

bringing to light, some new take on the unanswered questions arising

from that day, I’d be much more inclined to want to see this movie.

The

only reason I’m going to see it as of this writing is because George

asked me to participate in this discussion. Otherwise, I wouldn’t do it

for reasons that go back to what Slater said – we know that no matter

how brave they were, no matter what they did to save the further loss

of life, they all died. That’s an inarguable fact. Is it grief porn? I

don’t know, but when I first heard about it, without any other

information, that’s the first expression that came to mind.

Alan Cerny:

Alan Cerny:

I’m not even sure objectivity is a good thing when it comes to 9/11.

You ask anyone about that day, look at them, and see their faces as

they remember. Those are powerful emotions to draw from, and I don’t

know of any filmmaker who wouldn’t want to use them. In a way, all

historical films are exploitative. It may sound silly, but I didn’t

hear any outcry about "Too soon!" over films such as Saving Private Ryan or even Munich

and I’m certain there’s still people alive to remember those events. If

you’re making a movie about a historical event, by the very nature of

the medium it is exploitative. If a film is too objective you take all

the emotion out of your subject, and it becomes a case study. The film

may not be completely accurate, but a fictional reenactment can bring

an audience into a historical event in a way that, say, a documentary

made thirty years later would be unable to do. Granted, I haven’t seen United 93

yet, and if this film turns out to be some sort of rallying cry I’m

going to be sorely disappointed. So in that way a little objectivity

might be in order, to keep the film from becoming propaganda.

I

am completely sympathetic to those people, who for some reason or

another, don’t feel like they can handle the subject matter. If you

realy think it’s too soon for you to be able to see United 93,

don’t see the film, but please don’t judge those as crass who do. And

the film’s lack of objectivity can be cathartic. When it comes to me

personally, in a way that day still plays like a dream. It still

doesn’t feel quite real. I was a long way from the events when they

happened, and I remember seeing the shock on people’s faces at work

when the second plane hit the tower. At that moment we knew – this was

an attack. I never thought I’d live to see something like this happen

here. And maybe, in a weird way, this film will make it feel more real.

It may sound callous, but a fictional reenactment might be just the

thing for some people to accept what has happened, even now, almost

five years later.

Also,

I strongly believe that as far as evidence goes, this is a good as it’s

going to get, at least in our lifetimes. We’re never going to know

everything about that day.

Greg Clark:

Greg Clark:

I guess I’m going to sound like a bit of an echo chamber for a moment,

because I pretty much agree with everyone’s sentiments–the events of

9/11 are fair game for subject matter in films, same as they are in the

five million country songs about it, same as the countless hour-long

specials, same as the TV movies that all deal with the same thing. I

hate hearing that people are opposed to a film like this, using the

argument that it’s "Too soon!" I sort of see that argument more as an

ostrich technique than a legitimate fear–it’s easier to just push what

happened on that day out of your mind, try and forget it ever happened

(but say you remember anyway) or why it happened, until the only

response you have when someone says "9/11", you immediately shut down

in fear and simply give the speaker what they want. It happened to all

of us, collectively, in those months after 9/11, as various bearcats

touted the memory of what happened as a "Get into War Free" pass to

push their own agenda.

I think a movie like this is important. I

also think it’s important that, at the same time, the film needs to

remain honest. Not so much to keep total objectivity–because then it

becomes a visual history book, not a movie–but keep romanticism to a

minimum, or out of the deal completely. Romanticism sugar coats things,

somehow turns tragedy into entertainment (see Pearl Harbor and Titanic

for the worst offenders). I don’t want that in my historical films when

they’re trying to relate such awful events. Out of everything related

to this film, this is the only part where I give a moment’s pause.

Because we don’t know exactly what happened, some extrapolating has to

occur. And when the intent is to honor those who had the courage to

stand up and do what was right, how do you capture that without

devolving into patriotic flag waving? It’s a tricky question, one that

has faulted every attempt to capture what happened at The Alamo, and

that happened almost 200 years ago.

I don’t doubt Greengrass’

ability to present something that speaks higher than "Huzzah America!",

but for some reason I still have a lingering doubt, mainly out of how

those final moments are going to be played out. I keep seeing these

commercials on television, the ones with the tagline "On the day we

faced fear, we also found courage", and it makes me wonder. It might

just be marketing on Universal’s part to tap into a small amount of

jingoism to avoid controversy, or, in a worst case scenario, reflect

the film’s actual message. I say "worst case scenario" because I

honestly do not believe we, as a country, found courage on that day. In

those precious few weeks after the attack, yes. During that time when

it honestly did not

matter worth a damn if you were Republican or

Democrat, neo-con or pinko commie liberal. We were just Americans. We

had the chance to stand up, but instead we’ve fallen apart. We lost our

chance. I know people, people who weren’t even there, who say they look

up in fear every time they hear a plane, I’ve seen an entire classroom

of people fall silent when a Muslim

woman enters, seen the

suspicious glances. I see that still happening today, I see what’s

going on with our government, and I see no courage. And hopefully the

film will provide a message to us, not one of comfort or reassurance,

like the marketing seems to, but a reminder–a reminder of how much

we’ve let the people of United 93 down.

Jeremy Slater: I think YT’s question of whether this is "grief porn" is worth exploring. I mean, it’s hard to ignore the similarities between United 93 and Gibson’s awful Passion of the Christ. Both are asking audiences to watch people from recent and not-so-recent history get brutally murdered for 90 minutes in the hopes that their martyrdom will prove inspiring and cathartic. Both are largely fantasizing (or in Gibson’s case, fetishizing) events for which only partial records exist. Both are recounting a story that the audience already knows by heart. (Come on, The Constant Gardener is “a story that needs to be told”… Flight 93 is a story that has already been told many, many times.) So what’s the difference, folks? Can we still roll our eyes at Gibson’s grief porn without leveling the same charges at Greengrass?

Jeremy Slater: I think YT’s question of whether this is "grief porn" is worth exploring. I mean, it’s hard to ignore the similarities between United 93 and Gibson’s awful Passion of the Christ. Both are asking audiences to watch people from recent and not-so-recent history get brutally murdered for 90 minutes in the hopes that their martyrdom will prove inspiring and cathartic. Both are largely fantasizing (or in Gibson’s case, fetishizing) events for which only partial records exist. Both are recounting a story that the audience already knows by heart. (Come on, The Constant Gardener is “a story that needs to be told”… Flight 93 is a story that has already been told many, many times.) So what’s the difference, folks? Can we still roll our eyes at Gibson’s grief porn without leveling the same charges at Greengrass?

Hellboy: On the question of "too soon?", I would say no. Greenlighting the film in October 2001, and releasing in Sepember 2002? That would be too soon.

One of the survival mechanisms that we, as human beings, have hard-wired into our psyches is the ability to forget. I think the majority of Americans have forgotten what happened on 9/11. I think for many people in this country this is true. If they were not DIRECTLY affected by the events of that day, they have moved on with their lives. When I speak with friends in New York City, the subject of 9/11 almost inevitably comes up. When I speak with friends in Illinois, or Florida, or Texas – it never comes up. I think this is especially true when it comes to United Flight 93 and with AA Flight 77. These tragedies happened "offscreen" as far as media coverage is concerned, especially Flight 77, which struck the Pentagon. Flight 93 has a definite mythology – the cell phone calls, "Let’s Roll," etc., but we as a nation didn’t actually see them as we did with United Flight 175 striking the south tower of the WTC – "live." I would have to agree in this sense with Greg – if we truly remembered, we would not be in the state we are in today. We would not have let people politicize what happened that day. It seems for every attack on our personal rights and freedoms, for every false move we make as a nation – 9/11 is invoked. It is shameful.

I have to say that I HATE the poster for this film. Marketing took the easy way out. It’s manipulative, it’s jingoistic and it’s wrong. I had not initially intended on seeing this film during its theatrical run and the marketing materials were a big part of that decision. I have faith in Paul Greengrass to deliver a well-made film. I am sure the filmmakers did their best when it comes to accuracy. But this is a dramatization, and like any dramatization based upon a historical events (and a cloudy one, such as this), it will have a certain point of view. It will be subjective in its view. You can humanize the hijackers all you want to achieve "balance", but they are the villians of this piece and rightly so. Regardless of the little information we have been able to collect regarding the events of that day, we will never truly know what happened in that airplane. The only people who know can’t tell us.

Brendan Leonard: I like what people have said so far, and a lot of the points I hoped to address were adressed already. There are many articulate and intelligent people in this discussion, so I hope I don’t embarrass myself…

Brendan Leonard: I like what people have said so far, and a lot of the points I hoped to address were adressed already. There are many articulate and intelligent people in this discussion, so I hope I don’t embarrass myself…

As for the issue of whether or not United 93 will come off as propaganda. I think it certainly has that potential. The things that I’ve read from Greengrass and elsewhere seem to indicate that the film is being presented as the opening salvo in the war on terror. I remember reading the CHUD interview where Greengrass said the passengers on the flight were "The first people to live in a post 9/11 world."

So like films made during World War II about that war, I don’t think you can make an unbiased film about September 11 while we’re still engaged in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere. A film must have a point of view to be dramatic, and United 93 seems to have a very patriotic slant.

However, I do hope that Greengrass is able to present both sides with humanity and drama. In his movie Bloody Sunday, Greengrass (at least to me) came down firmly on the side of the protesters (and who wouldn’t), but one of the most painful things about his film Bloody Sunday was seeing how the British officers reacted. The looks on their faces as they realized that they were powerless to stop–that they could have stopped–the massacre was incredibly affecting. I hope that Greengrass at least gives us some insight into the humanity of the hijackers in United 93.

As for my personal interest in the film, I am anticipating it but I’m not all that eager to see it. I’m sure it will be a well-made, moving film that I will enjoy and get a lot of out of. However, as someone who lived in New York for the last three years, I think it’ll be pretty painful to watch. I wouldn’t dare compare myself to those who were in the city on September 11–I moved to the city about a year afterwards–but I do feel a deeper connection to it now that I’ve lived in the city. When you frequently pass by soldiers with automatic rifles on the subway, when you see Ground Zero at night, lit up but covered in shadows, the sheer size of the event hits you in a different way. The shot of the plane hitting the tower in the trailer–even though I’d seen it dozens of times in photos–made me wince when I saw it recently. I loved Bloody Sunday, and I think Greengrass has his head in the right place, but I am kind of nervous about how emotionally affecting the film might be.

Alan Cerny: I wouldn’t call it "grief porn," at least from my own standpoint. I don’t know anyone who died on September 11th. I can’t say I know anyone who knows anyone who died on September 11th. Sure, it may well be emotional for me to see it, but I’ll still have some distance from it. And Mel Gibson’s film really puts your face in it. It’s as if we’re dogs who pooped on the carpet. I can’t imagine Greengrass would do the same. It certainly won’t be as graphic. And we definitely know more about what happened on United 93 than we do about the actual life of Jesus, historically speaking. That story has had two thousand years to turn into myth. We haven’t done that (yet) with September 11th.

It’s weird that I feel this way about United 93, but I feel the opposite about Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center, which in my gut I know will be more exploitative, mostly because if there’s anything Oliver Stone can do better than Greengrass, it’s crass exploitation.

Brendan Leonard: Exactly. Gibson takes a sadistic pleasure in the gory details of Jesus’s death, as if the act itself is more important than what the act means. If United 93 was full of slow motion shots of the plane crashing into Pennsylvania and close ups of people being stabbed with box cutters, then I think you could make the argument. It seems that Greengrass realizes what the sacrifice and death of the people on that flight meant, and that why they died is more important than how they died.

Brendan Leonard: Exactly. Gibson takes a sadistic pleasure in the gory details of Jesus’s death, as if the act itself is more important than what the act means. If United 93 was full of slow motion shots of the plane crashing into Pennsylvania and close ups of people being stabbed with box cutters, then I think you could make the argument. It seems that Greengrass realizes what the sacrifice and death of the people on that flight meant, and that why they died is more important than how they died.

YT: I don’t think it’s too soon for this movie in that our sensibilities are too delicate to face the tragedy of the event head-on or that we should just try to forget it. But I do feel that this was such a monumental event in this country’s history and certainly in contemporary world events. I think it should be examined and reexamined in as many ways as possible to get to some approximation of the truth. That said, the resistance of this administration to let the truth be told in an open and unrestricted way, coupled with the compliance of the media to allow the official narrative thus far to be the correct one, leads me to believe that the information we have as of this moment in time is so vastly incomplete that it’s not worth dramatizing.

The reason that does make sense – though it wouldn’t coax me personally into a movie theater — is to have a piece of entertainment to allow those in need of catharsis to achieve some form of emotional release and possible closure. If the movie works to that end, then it’ll be successful.

I suspect Oliver Stone’s film will be similar to this film in that it’s going to be more about emotional catharsis than an unapologetic "conspiracy movie" a la JFK and I think that’s a shame. That is a movie I’d pay to see.

Alan Cerny: I’m all for a film that goes deep into the context of 9/11, from the training of the hijackers, to the massive security failure, to the days before and the days after, but this is not that film. That film really is probably years away, simply because we don’t have all the information. But I think it’s safe to say that this particular story can be told because if we don’t know the complete story, we can safely hypothesize about what we don’t know. United 93 is about the ordinary person’s reaction to extraordinary events, and I think from just a dramatic aspect alone that makes this story so compelling. You can’t show all of 9/11 in one film. But you can show facets.

Believe me, I’d like nothing better than a major studio release that excoriates the Bush administration, but we all know that’s not going to happen under the current climate. In that aspect we’ll have to wait.

Also, I’ll agree that that poster is terrible. It feels like a retarded marketing decision. If I had lost loved ones in 9/11 I’d be extremely angry about it too.

Hellboy: I just read a piece in the UK’s Guardian by John Patterson…

Hellboy: I just read a piece in the UK’s Guardian by John Patterson…

While I agree that we Americans may have a hard time confronting these things head-on at times, I do not agree with assertion that we do not understand the tradition of British-quasi-doc filmmaking. This is a Hollywood film, plain and simple. And while the director will undoubtably bring this sensibility so vaunted by Patterson to the project, it is still aimed squarely at American audiences.

Dan Whitehead: What I find interesting from a British perspective is how 9/11 changed the way Hollywood looked at terrorism. For years, other people’s real life torment had been fair game for American movies – and rarely in a respectful way. Who cares what it’s actually like to live in Beirut, or to have your family torn apart by an IRA bomb? Harrison Ford needs some bad guys to point angrily at, so lets co-opt that safely distant horror as backstory for the timeless villainy of Seamus O’Semtex, the rogue paddy with bombs on the brain!

After 9/11 it was almost like Hollywood finally realised that – wow – terrorism really kinda sucks. We should probably take it a little more seriously, huh? And that’s why I think the film is being received with a suspicious air outside the US. I get the impression that there’s some subconscious resentment at the idea that it’s only when it happened to "them" that the subject stopped being treated as a cartoon. I used to cringe at movies that used Irish terrorists as off-the-peg baddies because, from the perspective of someone who lived only a few miles away from two IRA bombings, it just seemed so crass and ignorant.

Of course, United 93 clearly isn’t that kind of film, but in the broad scheme of things I find the cries of "too soon" somewhat ironic.

As for the movie itself, I’m genuinely ashamed to say I’m not that interested in seeing it. The reasons why have already been lucidly explained by those before me – especially the Perfect Storm comparison – and while I’m sure Greengrass has approach the subject with tact and integrity, I still can’t see the wider purpose in fictionalizing or dramatizing something like this. I’m not saying they shouldn’t have done it, or that I refuse to see it, or that I think it’ll be a "bad" film – I just can’t find anything in the basic concept that makes me think "I can’t wait to see this". To use a phrase that I know annoys the beard off Devin, I don’t see what purpose it serves. I’m struggling to see how it can be anything more than a speculative reconstruction, and what there is to gain – artistically – from such an endeavour.

I keep seeing people using Bloody Sunday as the reason why Greengrass is perfect for the job, and I kinda see why. Both are dramatizations of real life tragedies, both are recent and fresh wounds. But with Bloody Sunday, I can immediately see the story. There’s a human drama there, and it is taken beyond the event itself and focusses on the aftermath – the fight for justice and recognition. There’s conspiracy and struggle. The only way could compare Bloody Sunday with United 93 is if it just told the story of the people who were shot on the march, and ended shortly after they were killed.

Another argument that I keep seeing, though is to counter the "too soon" plea which I don’t agree with anyway, is that movies about WW2 were made before that conflict finished, that Vietnam and Korea were dealt with on-screen within a few years. But United 93 isn’t a generic war movie. It’s about a specific event, with real life people, and a real life outcome.

Brendan Leonard: I think the Bloody Sunday comparisons also come from the way Greengrass is approaching the film–he seems to be focusing on not only the flight itself but the reactions to the day from people in the air traffic control room. That’s one of the parts of the film I’m most looking forward to, by the way. The drama of guys who operate under immense pressure the other 364 days of the year suddenly faced with this complete crisis has the potential to be just as uplifting as the story of the flight itself–out of the hundreds of flights in the air on 9/11, the only ones that crashed were the ones involved in the attack.

Brendan Leonard: I think the Bloody Sunday comparisons also come from the way Greengrass is approaching the film–he seems to be focusing on not only the flight itself but the reactions to the day from people in the air traffic control room. That’s one of the parts of the film I’m most looking forward to, by the way. The drama of guys who operate under immense pressure the other 364 days of the year suddenly faced with this complete crisis has the potential to be just as uplifting as the story of the flight itself–out of the hundreds of flights in the air on 9/11, the only ones that crashed were the ones involved in the attack.

As for America’s "new" reaction to terrorism now that we see that it sucks–well, I don’t think that’s entirely true. Not as long as you’ve got films like Collateral Damage and the Jack Bauer Power Hour on television. I think we’ve always been a culture of cartoonish exageration and bragging–the tall talle is an important part of our folklore–but we’re also a simplistic one. We like our sterotypes. We like our bad guys to wear black hats, our good guys in white ones and our supportive women in calico dresses. And as we’ve seen recently, when it comes to films like Munich and Syriana, we don’t like complexity.

After 9/11, the American myth-making machine kicked into overdrive. The media turned Rudy Giuliani–not the most admirable figure when he was mayor–into a saint, into the man of the year, into the Mayor of the World. "Let’s Roll" became a national slogan and we turned the people who died in the towers and on the planes into mythological figures. I remember watching the "Tribute to Heroes" special that aired recently–you have Tom Hanks (who begins his speech referencing the line from Flight 93, "We’re going to try and do something"), George Clooney, Robert DeNiro, and yes, Ray Romano telling stories from 9/11 with breathless reverance. (This may also come from the fact that America has no original mythology, so we canonize our great leaders–Washington, Jefferson, Kennedy, King–while ignoring their humanity and reinvent ourselves by inducting new gods–Babe Ruth, for example–to the pantheon.)

Which is a long winded way of saying that I think the way we treat terrorism in this country will be black and white for a long time. I hope to find some complexity in United 93, but as Paul pointed out, it is a movie for mainstream American audiences, and that means good guy-bad guy-clear moral.

Dan Whitehead: Munich and Syriana may not have set the box office alight, but then I don’t think anyone ever expected them to. My point is that pre-9/11 there’s no way a major studio would bankroll movies like that. Terrorism was seen as an easy way to come up with bad guys after the end of the Cold War. Can’t use Russians anymore, but terrorists…?

And it was almost always done in a casual way that betrayed the fact that America had never faced a real sustained terrorist campaign. Terrorism was narrative shorthand, easy backstory to set up the villains. The fact that these fictional terrorists had real life counterparts who were killing real people in Europe or the Middle East didn’t seem to matter – or was maybe even part of the appeal. That little frisson of reality injected into a safe fantasy world.

9/11 made the fantasy real for America. The word "terrorist" was suddenly not so much fun anymore. You could almost sense that audiences were flinching when it was used in the context of Swordfish or Collateral Damage. A kind of "that’s not so exciting anymore" vibe.

And my point is that this never mattered as long as the people being blown up in reality were somewhere in some desert country nobody could find on a map, or some Eastern European concrete hellhole, or even the streets of Warrington, Manchester or Belfast. Outside America the sympathy on 9/11 was perhaps eventually, as the whole grief industry set up stall, tempered with a feeling of "You realise this is nothing new, right? Some of us have been living with this kind of threat for decades."

Maybe. I have zero evidence to back this up beyond anecdotal and circumstantial observations, but I think there was definitely some resentment whenever it seemed like the world was being told that terrorism was some new and awful threat. Almost like it wasn’t an issue, wasn’t a real problem, until America got hit.

And I’m seeing this in some of the coverage of United 93 in the British press. It’s part exploitational "the trailer some cinemas refused to show" guff, and part "look at the yanks, milking it as usual". America is often seen as wearing its heart on its sleeve and, despite Greengrass at the helm, I think a lot of people outside the US may see the movie as being part of that mentality, that introspective emotional rawness that the USA stereotype is supposed to display.

It’s certainly not being covered with much reverence in the UK, from what I’ve seen. The mood seems to be "Typical Hollywood – can’t wait to make a movie out of everything".

I don’t agree with that sentiment, but it’s the vibe I’m getting from the British papers and TV. Mind you, I can’t imagine a British film being made about the final minutes of the people on the London bus that exploded last July either.

Jeremy Slater: Here’s a question for everybody: is there anything this film can really teach us?

Jeremy Slater: Here’s a question for everybody: is there anything this film can really teach us?

I know I keep harping on Gibson’s Passion of the Christ, but I think the analogies here go deeper than simple grief porn. Gibson’s cack-handed film was rightly criticized for its narrow scope–it showed us in excruciating detail how Christ died, but it never bothered to explain why that death was so significant for hundreds of millions of people. We learn nothing about the man’s teachings or his influence throughout history, merely the fact that his death really, really sucked. By focusing his scope only on the 90-odd minutes leading up to the crash of Flight 93, is Greengrass committing a similar mistake?

I’ll reiterate: I think it’s important for films to address the emotional scars that 9/11 left behind. And there’s a lot of fertile ground for dramatizing both the event itself and its aftermath–the way Kenneth Lonergan’s supposedly great script Margaret does–whether you’re examining, as Dan correctly points out, the way America’s views on terrorism shifted instantly, or the way some people seemed to be reveling in their vicarious grief, or the thousands of other stories still waiting to be told. Tell me about the conspiracy theorist searching for meaning in an endless loop of crash footage, or the girl so afraid of terrorism that she becomes a reclusive shut-in, or the estranged family driven to reunite because of their shared loss. Just don’t tell me a story I already know and expect me to walk away feeling enlightened.

So I’ll ask the rest of you: is there anything we can learn from a film like United 93? Because if this film isn’t making an artistic statement, if there’s no epiphany or subtext, then all you’re left with is a glossy episode of Rescue 911. You have to aspire to more than that. Because simply sending the audience home feeling queasy and shaken isn’t art…it’s exploitation. And I want to believe that Greengrass is better than that.

Alan Cerny: I can only respond as to how I hope the film affects me. To me much of 9/11 is muted. I know it’s a tragedy. I feel badly for all the lives lost and all the families robbed of loved ones. But it’s still academic for me in a lot of ways. When I see 9/11 imagery, to be honest, it’s not the tragedy of the event that comes to mind but all the colossal blunders that got us there. 9/11 makes me more angry than sad, and even then it’s almost like it’s a case study to me instead of a real event. Maybe, in a weird way, I haven’t dealt with the event as an American. You can ask me all sorts of questions about 9/11 and I can try to respond, but the one question I know I can’t answer satisfactorily is "How did 9/11 make you feel?" I know this sounds all touchy-feely tree-huggy, but a lot of what I love about film is the emotional journey that good ones take you on, and maybe in some small way this film can make me understand what 9/11 really did to people on a personal level. I know that sounds cheap and like a cop-out, but it’s what I think.

Greg Clark: I suppose that’s something we won’t be able to determine until we actually see the movie–maybe there will be something in there that turns a light on in people’s heads, makes them look at what happened there in a different light. I don’t think it’s grief porn, at least, not in the extreme that The Passion was. Everyone knows how Christ died–bloodily and painfully. Watching The Passion is almost titllating–waiting for the whips to come out, waiting to see the nails go into the hands. You know it’s happening. You’re expecting it, almost morbidly getting excited to see it, to revel in how awful it’s going to make you feel. I’d like to think Greengrass is taking a much more sober, somber look. With United 93, so many people don’t know anything outside of the romanticized version of events, the propagandist recreation and exploitation of it, that if Greengrass shows just how things went down, it might offer a new perspective on things. Or, perhaps, it will work as a reminder, to offer a dose of reality to the masses the difference between standing up and acting courageously–which the people of Flight 93 did–and what our country has laughingly called courage in the years since.

Greg Clark: I suppose that’s something we won’t be able to determine until we actually see the movie–maybe there will be something in there that turns a light on in people’s heads, makes them look at what happened there in a different light. I don’t think it’s grief porn, at least, not in the extreme that The Passion was. Everyone knows how Christ died–bloodily and painfully. Watching The Passion is almost titllating–waiting for the whips to come out, waiting to see the nails go into the hands. You know it’s happening. You’re expecting it, almost morbidly getting excited to see it, to revel in how awful it’s going to make you feel. I’d like to think Greengrass is taking a much more sober, somber look. With United 93, so many people don’t know anything outside of the romanticized version of events, the propagandist recreation and exploitation of it, that if Greengrass shows just how things went down, it might offer a new perspective on things. Or, perhaps, it will work as a reminder, to offer a dose of reality to the masses the difference between standing up and acting courageously–which the people of Flight 93 did–and what our country has laughingly called courage in the years since.

Emotionally, though, it might give people more of a connect to that day. So many people have pushed it out of their minds, have been actively doing so since it happened, that the disconnect is wider than ever, and growing. 9/11 occured a mere half decade ago, and it already feels like a myth, the sort of long-ago event you read about in history books, like Pearl Harbor or the Civil War. People remember the idea, but not the event, and a film like this–assuming it doesn’t pander–could serve as a wake-up call.

Or it could just agitate viewers to stick their head further in the sand, moaning about those damn liberals in Hollywood exploiting our precious feelings.

Brendan Leonard: That’s exactly what I was going to say, and I think that one of the reasons 9/11 has already become so mythologized is that we don’t want to admit what’s happened since. Like Greg said, recognizing the true heroism of that day means we have to take a long hard look at ourselves since.

But while the optimist in me hopes that United 93 might–at least for a few people–serve as a wake-up call, America’s become polarized that it’s impossible to have any real debate or discussion any more. I can just see Bill O’Reilly going on his show and saying that this film is liberal claptrap because it "humanizes" the terrorists.

John Carroll: Slater asks if there’s anything we can learn from United 93, and having seen the film last week, I’d like to chime in and answer "yes."

I have a feeling that the phrase "most important film of the year" will be tossed around these next few weeks when the film opens, but I feel that it’s very appropriate, and not just because what we’re dealing with is heavy subject matter.

Greengrass is very detailed in his approach, but without having the blow-by-blow account of what happened on that flight, there’s much left to the imagination.

I’ve made the comparison in private conversation, and I’ll make it again here — Greengrass’s approach very much reminds me of how E.L. Doctorow treats history in novels like Ragtime or The Book of Daniel. That is, the greater sense of things is far more important than the timeline of events.

And that’s what makes United 93 a challenging film, an important film, and — to answer Slater’s question — a film from which we can learn. It’s not just about dealing with 9/11. On that level alone, it’s a powerful and disturbing film that will rattle you. But in taking the approach that he does, Greengrass is raising deeper questions about art and who has the authority to tell certain stories.

There are certain moments in United 93 where I just wanted to leave the theater. I was bothered by the liberties that Greengrass took, and for those several brief moments I thought the film was not necessarily "too soon" (I don’t think it’s anyone’s right to say what an artist can or cannot express), but not necessary.

Ultimately, though, I think it’s Greengrass’s attention to the greater lessons of United Flight 93 that pushed me past my few misgivings. I’m coming at the film from a college curriculum that I structured around the idea of authorial power in contemporary art, so I’m sure my concerns won’t be those a wider audience. Still, I think the issue of who can tell what stories is just as relevant to the film as the tragic events at its core.

What Greengrass does with the film is tell a partial history. And that’s why I have to disagree with Slater’s comparisons to Passion of the Christ. With that story, the ending only takes on its full relevance if the rest of Christ’s story is told. With United 93, the flight passengers only become a part of the bigger whole through the storytelling that we did afterwards — whether in conversation, newspapers, magazines, or elsewhere.

By focusing as he does, Greengrass tells only one of 9/11’s stories so that he can illustrate the greater points he sees in it — that of America’s confused response and of the passengers’ roles as the first citizens of a post-9/11 America.

So while I think there will be many fiercely contested debates once this film comes to theater, I don’t think "Can we learn from it?" will be one of them. I hope it isn’t, anyways.

Jeremy Slater: But is it really news to anybody that 9/11 was a confusing, frightening day? That the passengers were some of the first Americans forced to confront terrorism head-on? These seem less like lessons and more like no-brainers to me.

Jeremy Slater: But is it really news to anybody that 9/11 was a confusing, frightening day? That the passengers were some of the first Americans forced to confront terrorism head-on? These seem less like lessons and more like no-brainers to me.

In Devin’s thoughts on the film, he says: "The books can tell you what happened, but the movie lets you know how it felt. That’s the place for art. But actually, on second thought, I’m wrong. Art isn’t about letting you know how it felt – art is about letting you feel how it felt."

And I guess that’s the point I’m clumsily circling, because these are the exact same things that people were saying in defense of Passion of the Christ. That the film was a masterpiece because it allowed you to really FEEL what it must have been like for poor old Jesus. Which was an argument I didn’t accept then, and I sure don’t buy it now. The people who were being devastated by Gibson’s film were the people who already had an emotional connection with the material before they ever stepped foot in the theater. I’m not accusing Devin or anyone else of bias, but this is a film that’s not going to have the same impact on every viewer. And hypothetically speaking, if I have to bring my own baggage into the theater in order to truly *experience* United 93, is it still art?

Look, Passion of the Christ can make me feel how it feels to get the holy shit whipped out of you. Rescue 911 can make me feel how it feels to be stuck in a well. Hostel can make me feel how it feels to get your tendons severed. I’d argue that art *has* to be more than that. Art has to present an argument or challenge your viewpoints. It has to make a statement…otherwise it’s just an exercise in reenactment. An exceptionally well-made and unflinching reenactment, perhaps, but a reenactment nonetheless.

Alan Cerny: Because most every American can relate to

being on an airplane, as opposed to having Roman centurions beat the

crap out of you (barring strange fetish clubgoers). Plus, we all have

a direct line to that day. None of us were here the day Christ died.

But we all were here on 9/11. I see where you’re coming from, and all

I can say is that I think it’s a valid reason to avoid the film. But

maybe for those people who were directly affected by 9/11, this film

will be some sort of closure for them, and for that reason alone I

think it’s worthwhile.

John Carroll: One of the reasons I was reluctant to jump into this argument is because I didn’t want to throw out this answer, but, well: You haven’t seen the film.

John Carroll: One of the reasons I was reluctant to jump into this argument is because I didn’t want to throw out this answer, but, well: You haven’t seen the film.

The argument that the film won’t have the same impact on every viewer isn’t much of an argument, as it can be made in regards to just about every work of art.

I’d like to think in my previous response that I mentioned some of the things that make United 93 more than just a reenactment. I don’t think I walked into the film with much baggage, and I walk out of the theater reeling. And not just because it’s a terrorists attack America film, although that certainly and obviously affects the audience as well.

It is a film that makes a statement and challenges its viewers. About terrorism, about our nation, about art and stories. It stirred up a lot in me, and about a lot of issues that I didn’t expect. The lessons that you call "no-brainers" are only one part of what this film is about.

One thing that I didn’t mention in my previous entry was the treatment of the terrorists in the film. It’s very … ambivalent. While I personally was prepared for that, I think a lot of viewers who come into the film with an "us against them" attitude are going to be very challenged by how these men are presented. This isn’t Pearl Harbor where the evil music comes on when the Japanese are on-screen.

And again, the idea of these terrorists as men with their own goals and beliefs will certainly be a "no-brainer" to some, myself included. But I think it’s a very quiet and subtle challenge of the way these terrorists are presented in most accounts of 9/11 Either way, I think my larger point is this: I believe that Greengrass has carved out something with this film that has many things to say, and will wind up affecting most of its viewers in some way. And that may mean pushing some of its viewers to hate the film.

Perhaps it’s just a matter of having seen the film vs. not having seen it, but I think a lot of the questions you raise, Slater, ultimately aren’t relevant. I certainly don’t think that Passion of the Christ has much of a place in this discussion. But again, maybe it’s just a matter of our relation to the film — I’ll be interested to see if you stick to the same issues after having seen the film.

Jeremy Slater: It’s always tough to argue about a film on a purely conceptual level with people who have already experienced it firsthand. I still have a lot of reservations, but I’m encouraged by what John and Devin have said, and I hope Greengrass can prove me wrong. Thanks for putting up with my contrarian bleating, folks. It was fun.

YT: I’ve really

enjoyed reading and participating in this discussion. I don’t think I

have anything more to contribute until I see the movie because I still

don’t have enough of a sense of what it is. But bravo, everyone. It’s

been a pleasure!

Alan Cerny: We don’t get many so-called "important" films anymore, unless they’re Oscar bait, and even then they aren’t as important as they probably want to be. I’m certain that

BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

If this article were written in the mid-1990s, it would have a holo-foil die-cut cover and a variant by Stephen Platt. But this is 2006 and there’s far more profit to be made in feature films, so here’s sort of a "state of the union" regarding Marvel’s slate.

If this article were written in the mid-1990s, it would have a holo-foil die-cut cover and a variant by Stephen Platt. But this is 2006 and there’s far more profit to be made in feature films, so here’s sort of a "state of the union" regarding Marvel’s slate. Sitting down before

Sitting down before  Marvel’s shiniest hero (well, the one who doesn’t surf) has a new director.

Marvel’s shiniest hero (well, the one who doesn’t surf) has a new director.

Paul Greengrass was the last person I spoke to on the very long

Paul Greengrass was the last person I spoke to on the very long  Q: Have they all seen it at this point?

Q: Have they all seen it at this point? Q: It drives me nuts.

Q: It drives me nuts.

Alan Cerny:

Alan Cerny: Greg Clark:

Greg Clark: Jeremy Slater:

Jeremy Slater: Brendan Leonard:

Brendan Leonard: Brendan Leonard:

Brendan Leonard: Hellboy:

Hellboy: Jeremy Slater:

Jeremy Slater: Greg Clark:

Greg Clark: Jeremy Slater:

Jeremy Slater: John Carroll:

John Carroll: