Anthony Hopkins is grandfatherly. He’s soft spoken and

Anthony Hopkins is grandfatherly. He’s soft spoken and

laughs a lot and seems to happy to get his reminiscence on, just like a

grandfather. After meeting him it’s hard to imagine him eating Ray

Liotta’s brain – and then right at the end of the interview he did that

lip smacking noise that Hannibal makes when he does the Fava Bean

speech – and you’re suddenly creeped out.

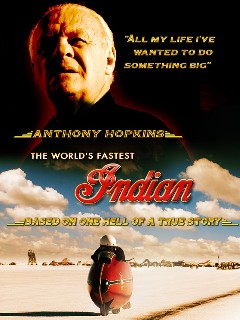

Hopkins’ newest film is The World’s Fastest Indian,

which does not have him playing Gandhi breaking the four minute mile, but rather a New Zealander named

Burt Munro, an old coot with an old Indian motorbike who wants to

travel to America to race his souped up cycle at Bonneville Flats

speedway, to see how fast he can make it go. It’s a true(ish) story –

director Roger Donaldson knew the real Burt Munro, and made a

documentary about him called Offerings to the God of Speed.

The World’s Fastest Indian is coming to theaters this weekend.

Q: When did you first hear of Burt’s story, and why did you want to play him?

Hopkins:

Roger Donaldson sent me the DVD of the documentary and the script and

he said, “Watch the documentary first and then read the script, tell me

what you think.” So I watched the documentary and thought it was very

good. I read the script the next day and phoned him and said I’d like

to do it.

Q: Burt’s got such a wide-eyed view of the world.

Hopkins:

Yeah, it’s a bit like me when I came to America. I’m pretty wide-eyed.

I’m always taken by surprise by things. And that’s how I’ve treated my

whole life actually—always being in a straight of surprise. I moseyed

onto this train called show business many years ago, and I’m still

going. So it’s a pleasant journey.

Q: That seems to have changed, because in the press notes you mentioned working with Roger on The Bounty

and said you were much more temperamental back then, and that you would

argue or scream with a director. I’m wondering if you’ve just mellowed?

Hopkins:

Yeah. Well, Roger was the same—we met about 3-4 years ago at a party

and we’ve both mellowed out a bit. I think as you get older, you get a

bit more sensible, get a better perspective of things. I figured out

some years ago that the director is in charge of the movie. That

doesn’t mean to say that every director is good or every actor is good,

but the director—that’s his job to run the movie, he’s the boss. I

remember the first day we were filming, when the wheel comes off the

trailer, and Roger said, “Can we do another take?” and I said “Yeah,

you sure?” So we did about 15 takes. [laughs]. He’s a perfectionist and

he wants to get it right, and I imagine this is the program, just go

along with it.

Q: When you look back at your younger self, do you say ‘What a hothead I was!’ or ‘Why was I that way?’

Q: When you look back at your younger self, do you say ‘What a hothead I was!’ or ‘Why was I that way?’

Hopkins:

I don’t regret it, that’s the way it was then. When you’re younger you

have a lot of ideas and you’re probably more insecure, all those

things. I work with young actors now and I see their insecurities and I

make fun of them. I don’t make fun of them but I make them laugh,

because I know what they’re going through. When you get older you think

‘It’s only a movie after all, it’s not brain surgery.’

Q: You have said that you became an actor because you didn’t do well in school.

Hopkins:

I just probably couldn’t figure out anything when I was in school and

so I became an actor because I didn’t know what else to do.

Academically I wasn’t good. I was just slow or different. I remember

kids in school who could understand math, and we had one guy in school

who was a genius, and I don’t know what happened to him. He ended up

driving some truck, and he was brilliant in school, good student. David

Davis his name was—amazing, and I hated him (laughs). He never did any

homework and he just got it all the time. I didn’t have that kind of

mind structure and I think we’re all different. Some people are

musicians, some people are actors, some are accountants, agents,

newspaper guys, drivers, etc.

Q: How has your approach to roles changed in recent years?

Hopkins:

I’ve always taken the same method, which is to learn the lines

literally. I learn the text, I read the script maybe twice, and I go

over my text of the lines. I get a rhythm in my head and then I can

hear rhythms which click. With certain rhythms of speech I think, ‘This

is interesting’ and I let them take me into a new area. I begin to feel

like someone else—I’m not schizophrenic or anything—but just to use

another rhythm of my own self.

Q:

Burt feels like his whole life has been leading up to that first race

that’s portrayed in the movie. Do you feel that you’ve had your

Bonneville moment or do you feel like you’re still waiting?

Hopkins:

I feel like when I first came to New York, 30 odd years ago. I remember

I had been living in England for years and wanted to come to America. I

remember getting up in the morning at the Algonquin in September in

1974, and I went on 5th avenue to get a newspaper and I thought, ‘I’m

home’. I had that feeling about it, and that scene where Burt arrives

at Bonneville, I’d learned that speech and not that it’s a huge moment

being in Bonneville because I’m not interested in world speed records.

But I remember doing that scene, it was a cold morning and Roger said

“Action!” and I got quite emotional about it, because it was similar to

my own life in a way.

Q: Which role has eluded you the most? Which did you find the most difficult?

Hopkins: I

think Nixon. To play an American President, that’s a bit of a stretch

of imagination [laughs]. Oliver Stone is an amazing director and he put

the pressure on. I didn’t want to do it, and I remember he came to

England to meet me and I’d already turned it down. He said, “Chicken,

huh?” [laughs].

I

remember going to meet him on that morning at the Hyde Park Hotel, and

I had a moment of clarity—I can stay here in Britain and play nice,

boring safe parts in BBC [snore sound], or I

can work with this crazy director in America and maybe fall on my

backside or make a success of it. I just thought well, I’ll just take

the risk. And I went to the hotel and Oliver gruffled and said

“Chicken, huh?” and I said, “No, I’m going to do it.” I said yes and I

went to America and I remember learning the script and thought, ‘What

have I done? I’ve taken on this nightmare.’ Then I went to California

and started rehearsing and realized I was in the hands of a great

director. He puts a lot of pressure on you, and you get to a point

where you either crack or you get it. He was relentless until I got the

feeling of the part, and I really liked Oliver.

Q:

When you’re playing a real person like Nixon or Burt, how important is

it for you to be accurate to that person, and how important is it to

have freedom to create your own character?

Hopkins:

If you get accurate—I mean, I can never become accurate. I don’t look

anything like Nixon or the real Burt Munro. Nixon’s face has got a long

nose. We tried to make a nose and all that and I said ‘This isn’t

working’ and they did the hair. But if I was Rich Little or Fran

Gorshin or these great mimics, they’re brilliant. Actually Rich Little

came to the set of Nixon one day and I resisted doing Rich Little,

because if you do that, you become a mimic. And with an accent like

this guy—a New Zealand accent—if you strive to get it absolutely

accurate then it’s not a performance; it’s a mask. You may as well make

a Nixon funny head or a Burt Munro mask, because that’s not what acting

is about. That’s my opinion. So you just airbrush it in, a couple of

pen strokes here and there. The New Zealand accent was easier for me

because Burt sounds a little bit Cornish or Irish, so it was easier

than North Islanders, which are a much more pinched sound.

Q:

There was a poll done by the Old Vic Theater and you came off as the

number one British actor of all time, ahead of Laurence Olivier, Alec

Guinness, Michael Caine…and Judi Dench was your counterpart. Do you

think you’re that great?

Hopkins:

I honestly don’t know. It’s a source of puzzlement for me, and I’m very

pleased if they call me that. I thought a lot lately about it, and I

honestly don’t know. I blush a bit, because I worked with Olivier and

he’s a great actor. And I’ve seen those guys like Alec Guinness. It’s

great to be told that, but I remember thinking I’ve gotten a few

enemies in England now. Maybe I have an attitude, and I don’t know

what’s happened to me over the last few years, except that some things

opened up in me and… I don’t take it seriously.

But

I do my job, and I do what I’m paid to do and I’m always prepared. I

prepare by learning the text so well that when I show up, I’m relaxed

and the performance sort of happens. Now whether that’s good or bad, I

don’t know, and I’ve been in some films that were bad and given some

bad performances as well. But maybe people respond in a way—whatever I

say is going to sound very egocentric and self centered anyway so I’d

better shut up. But when they say that, I think ‘oh well’. I got the

Cecil B. DeMille Award recently…but I’m still up there thinking, ‘Have

they got the right person’? [laughs] I still do that.

Q:

Q:

You’ve spoken a few times about rhythms and sounds, and finding

character. I think you also compose. Is there a connection there? Is

that one of your major ways into your art?

Hopkins:

I suppose so. I don’t necessarily analyze it but I started off when I

was a little kid playing a piano and I wanted to be a musician. I say

that in retrospect, I don’t know how much I wanted to be. I just wanted

to be famous because I wanted to escape from what I felt was my

limitation in life because I wasn’t a good student. And I wanted to

write music, and I didn’t know what I was doing and I never had the

technique or understanding of it. Academically, I don’t grasp things at

all well. But I’ve always played the piano and I can improvise on the

piano, but the problem is that I can’t write down what I write. I can

read music but I can’t write numbers; I don’t have knowledge. My wife

said, “That’s beautiful, why don’t you get some help?” so I phoned up

somebody who she knew, whose a composer and musician in his own right,

and I went to his studio and he gave me the freedom of his studio where

I could synthesize a keyboard. I know my way around instruments so we

became good friends, and he’s got no ego at all. He helped me with all

the electronics stuff on the computer because I don’t understand that

but I’m learning. And I’m learning orchestration.

I

built the first big piece I have called “Margam,” which is where I was

born. It sounds pretty good, and it’s being performed in San Antonio in

May in the symphony orchestra down there. Music has always been with me

but my wife sort of turned the key in me and said I am a musician. And

with paintings, she got me to do some paintings for this gallery in San

Antonio again. So we’ll be combining an art exhibition — it sounds like

a real ego trip, this [laughs] — but she said she wants me to do 100

paintings for this little gallery. So I did these little pen drawings,

with felt pen and brushes. So I paint these landscapes and I change

colors, and she got me to do acrylics. I’ve done 25 acrylics for the

library and I go down to San Antonio on Thursday to see the orchestra.

I figure the thing is not to analyze it, and people say ‘Oh you’ve got

no technique’ and I said to hell with it, people seem to like it and

they want to buy it [laughs]. I think it’s all a happy design. I’m not

saying I’m Picasso, but I do enjoy the freedom of free expression

without knowing anything about it.

Q:

It says in the notes that you’re a happy man, and because of that you

don’t really want to play villains or psychotic people anymore. Is that

true?

Hopkins:

Oh, yeah. But actually my next movie is with Ryan Gosling and I play a

man that kills his own wife—she’s having an affair—but it’s not

Hannibal Lecter. This man is a little

strange but he’s on the surface very normal, very quiet, and he kills

his wife because she’s having an affair. It’s a revenge thing but he

sets up a test. This guy is involved with those Ruth Goldberg machines

and he designs the perfect murder but he leaves one flaw.

Q: Is it true you’re coming to do narration for the next Hannibal film?

Hopkins: No, that’s a dumb rumor.

Q: So you’re all done with Hannibal?

Hopkins: Oh, yeah.

Q:

At the Golden Globes when they gave you the De Mille award, they said

(about Hannibal), this is the #1 villain of all time in the movies. Did

you find, in a way, that is a thing around your neck? A hard thing to

get rid of?

Hopkins: No, but people want me to do the Fava Bean speech all the time.

If you’ve been dying to see what big time explodo director Roland Emmerich might find to blow up in prehistoric times, Warner Bros is your friend. They’ve picked up his

If you’ve been dying to see what big time explodo director Roland Emmerich might find to blow up in prehistoric times, Warner Bros is your friend. They’ve picked up his  Ridley Scott is kinda like Steven Spielberg or David Fincher in that he always seems to be orbiting a number of projects but only rarely sets down the skiffs. Commitment-phobic? Capricious? Overly ambitious? Hey, if it means we don’t get another G.I. Jane, take your sweet time deciding, Sir.

Ridley Scott is kinda like Steven Spielberg or David Fincher in that he always seems to be orbiting a number of projects but only rarely sets down the skiffs. Commitment-phobic? Capricious? Overly ambitious? Hey, if it means we don’t get another G.I. Jane, take your sweet time deciding, Sir. I’ll save most of my snark for Oscar night, when we’ll probably do the traditional running commentary on the site and/or message boards here. But my initial impressions? I’d like to see Munich or Good Night, and Good Luck in the Picture, Director and Actor categories. I think that despite being in a town notorious for flexible morality, the Academy is just too uptight to give many awards to Brokeback Mountain, but I could be mistaken (knowing them, they’ll give it to Crash). Walk the Line could be a contender in a few categories, and it’s nice to see A History of Violence at least get notice, however minor. Not a strong showing for Peter Jackson’s big gorilla.

I’ll save most of my snark for Oscar night, when we’ll probably do the traditional running commentary on the site and/or message boards here. But my initial impressions? I’d like to see Munich or Good Night, and Good Luck in the Picture, Director and Actor categories. I think that despite being in a town notorious for flexible morality, the Academy is just too uptight to give many awards to Brokeback Mountain, but I could be mistaken (knowing them, they’ll give it to Crash). Walk the Line could be a contender in a few categories, and it’s nice to see A History of Violence at least get notice, however minor. Not a strong showing for Peter Jackson’s big gorilla.

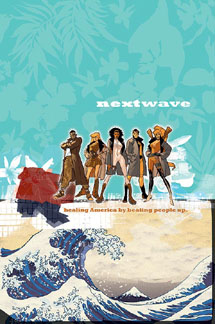

It’s official, comics are indeed fun again.

It’s official, comics are indeed fun again.

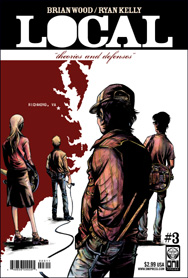

For most of us, the conceit Brian Wood and Ryan Kelly use for Local is just that—each story is set in a different American city and, as such, is a nice hook upon which you can hang quiet, small dramas.

For most of us, the conceit Brian Wood and Ryan Kelly use for Local is just that—each story is set in a different American city and, as such, is a nice hook upon which you can hang quiet, small dramas. If I were to say that the Star Wars prequels were a bit disappointing, I wouldn’t be the first.

If I were to say that the Star Wars prequels were a bit disappointing, I wouldn’t be the first.

I hadn’t realized until picking up this collection (which is a repackaging of Across the Universe trade but with The Killing Joke added in) that Alan Moore had spent such a limited amount of time in the DC Universe playground.

I hadn’t realized until picking up this collection (which is a repackaging of Across the Universe trade but with The Killing Joke added in) that Alan Moore had spent such a limited amount of time in the DC Universe playground. Liz Prince’s debut graphic novel, Will You Still Love Me If I Wet The Bed? wowed them at last year’s Small Press Expo, winning the Outstanding Debut Ignatz award.

Liz Prince’s debut graphic novel, Will You Still Love Me If I Wet The Bed? wowed them at last year’s Small Press Expo, winning the Outstanding Debut Ignatz award.

There’s nothing worse than thinking you’re funny/hip/edgy when the reality is you just absolutely suck. That is the reality of the Razzies, a relatively harmless novelty award that rewards films in the field of shittiness. Yet, why do they still seem to piss me off? I don’t know. It’s like that guy on our message boards who thinks he’s the funniest thing since midgets, Chuck Norris, or

There’s nothing worse than thinking you’re funny/hip/edgy when the reality is you just absolutely suck. That is the reality of the Razzies, a relatively harmless novelty award that rewards films in the field of shittiness. Yet, why do they still seem to piss me off? I don’t know. It’s like that guy on our message boards who thinks he’s the funniest thing since midgets, Chuck Norris, or  I have complete faith in Sam Raimi et al when it comes to the

I have complete faith in Sam Raimi et al when it comes to the