Welcome

Welcome

to Videodrome. I try not to set goals, but if I did, and if Devin won’t

sabotage me with his commie psychic ray, this should resemble a weekly column

that supports the cool stuff Dave does in the Underground by focusing on

directors and small groups of related films that Chud might otherwise miss.

Strangely enough, psychic rays are a large part of this first installment…maybe

the bearded liberal is already undermining me.

Eventually,

this will be less about reviews and more interested in pointing out all the

unbelievable stuff that’s now commonly available thanks to DVD. New is OK, but

older is great. To begin I want to go back a few years to Japan, from

1988 to 1996.

Cyberpunk’s Not Dead

The Matrix killed cyberpunk for me. Even

worse, it did the job in a way the genre would admire: by mutating it into

something that was almost recognizably ‘cyberpunk’, yet totally different.

Bigger, harder to control, and sadly much less useful. Granted, the term was

always pretty lame. William Gibson has tried his damndest to preserve a

literary notion of the genre, but for most people it’s just The

Matrix. Mention that Rubber’s Lover is cyberpunk, and

they’re going to expect something shiny and high-minded.

To me,

cyberpunk is forever dirty, street-level sci-fi. The word ‘punk’ ain’t in there

for nothing. It’s the passion of the Sex Pistols or Bad Brains, where it’s not

enough that the people in the songs are desperate. The music, and these films,

wouldn’t work if they didn’t use that same energy to push back at the audience.

And

all-important, buried in the grit was always the question: ‘What would you do

to transform yourself?’ That question, of course, is as fitting in the

Videodrome mindset as it is in the three films I recently watched: Tetsuo

The Iron Man, Pinocchio √964

and Rubber’s

Lover. All of these movies are fitting tributes to the idea behind Videodrome,

so they’re a pretty good way to kick off the column.

Whenever

you’re mutating into something glistening and new, a proper foundation always

helps. So I’ll kick off with a revisitation of the landmark flick that some

love to copy ande few have actually seen…

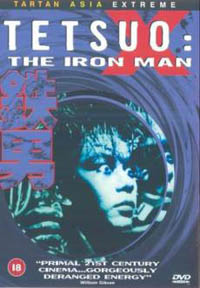

Tetsuo The Iron Man

(1988, Japan, Shinya

Tsukamoto)

Specifically,

Specifically,

there are a couple of reasons I’m beginning here. First, the two Fukui films that follow

borrow so heavily from Tetsuo that it’s pointless to

discuss them without mentioning Shinya Tsukamoto’s pioneering film. Second is

that it had been at least ten years since I’d seen the film, and it was high

time for a refresher course. Finally, I see dismissals all over the internet

written by lazy-ass commentators who proclaim it to be impenetrable trash.

Balls. Tetsuo is overbearing and off-putting, but not difficult to

follow, as long as you’re paying attention.

Tetsuo also brings in the Davids, Lynch

and Cronenberg, both of whom are acknowledged by Tsukamoto. Setting aside the

obvious ‘body horror’ component — which I’d say is symptomatic of what’s

really going on in the film — Tetsuo looks a lot like Japan’s answer to Eraserhead.

The general aesthetic, the sound design and starkly interior nature of the real

story are all a contract-print reproduction of Lynch’s debut.

The film

lives in decaying urban spaces. A man, ultimately identified in the credits as

‘metal fetishist’, cuts a large slit in his leg, into which he slides a long,

threaded rod of metal. Images of famous runners adorn his workspace, which make

his transformative desires pretty clear: could this process bestow a new speed

and power? It’s just as obvious that something has gone wrong when the photos

all erupt in flashes of fire. In case it’s not obvious enough, however, we see the wound

crawling with maggots desperate to consume the decaying flesh.

The bolt, we discover, was infected with rust. Try to stop that pernicious orange virus. Staggering into the street, the

fetishist is struck by a car. The salaryman behind the wheel, terrified by the

consequences of his action, drags the wounded man off to the woods, where the

victim slips from consciousness as the salaryman and his girlfriend work out

their desires for hot tree sex. You’ve got to wonder how much free will the

driver really had, since his car seems to have tattooed ‘New World’ on it’s

metal grille.

And

that’s where everything breaks.

Back

home, the salaryman is infected by a sliver of metal from his shaver, a

stainless steel injection. The metal which took over the fetishist, that urban

spirit, now begins to control the salaryman as well. He quickly undergoes one

metamorphosis after the other, quickly outpacing The Guyver in the ‘most

uncomfortable costume’ race. On the other side of town, the fetishist lives,

and he races to face the salaryman in a lustful battle royale. The scorecard

says: unclean infection versus pristine transformation. It’s better than When

Godzilla Attacks!

But like

I said, the method of transformation is only indicative of the underlying idea.

Sure, it’s important that it’s metal; how better for the urban landscape to

rape mankind? Only concrete would be more effective, but it’s so inflexible.

The real

battle is between the willingly transformed (fetishist) and unwilling

(salaryman). It’s tragic in a way, because the fetishist desperately wants to

become something else, but he’s blown it. His adversary, on the other hand, has

an almost unhealthy lust for human life (and tree sex) and fights the

inevitable with all his will. Their battle is a half-hour chase scene through

the back streets of Tokyo.

Finally, there’s a sort of compromise that promises the metal that ‘new world’

it so desires.

(Miike

did his own transformation of this ending for Dead Or Alive: Final.

Shinya Tsukamoto himself appears in Ichi and DOA 2: Birds.)

It’s easy

to just get caught up in the spectacle of the conflict. Tsukamoto barrages us

with images that are sickly and revolting — rotting flesh, the penis drill,

strap-on tentacles — but he does it in a way that’s impossible to look away

from. It’s hyper-kinetic stop motion swirled through the lens in high contrast

black and white. He almost hyperventilates this film (it runs a mere 67

minutes) and even the flashbacks, which imply that the metal’s memory is

television, offer a tense but swift fascination.

Chu

Ishikawa bangs out an aural equivalent to the harsh landscape, channeling

Einsturzende Neubauten and Big Black into a set of songs that become the

movie’s mechanical pulse. But then he drops into a ’50’s milkshake dance number

whenever the film’s automobile hero hits the stage, equating the love and

enmity for metal with a crazy Norman Rockwell puppy love.

In the

years after Tetsuo, the film’s content was echoed in legions of followers.

Some were obvious (the Raimi-esque follow-up Tetsuo II: Body Hammer)

while others essentially returned Tsukamoto’s affections — take another look

at James Spader riding Roseanna Arquette’s leg in Crash.

But more

immediately in the film’s wake was a kinetic pair of films from Shozin Fukui,

and they’re up next.

(Tetsuo

is tragically out of print in the states, though DiabolikDVD.com

and other importers carry a legit Region2 PAL disc.)

Pinocchio √964

(1991,

Japan, Shozin Fukui)

Fast

Fast

forward three years. While Tsukamoto was making Tetsuo, Shozin Fukui was

cutting his teeth shooting documentaries and musical performances. He was also

nurturing ideas for a film that could explore a different kind of

transformation: the evolution of the mind through the pressure of physical

pain. He evidently took the structure and style of Tetsuo as a mandate,

because this story of a displaced sex android is like that film’s awkward

younger brother.

Pinocchio

(who I’ll just call 964 from now on) is the android in question, an object cast

onto the street by an unsatisfied client. Built (or grown) solely to pleasure

others, 964 has no memory and no sense of the outside world. Wandering the

city, he meets Himiko, herself an amnesiac who seems to recognize something

about the poor guy, and quickly befriends him. As 964’s creator sends out a

search party, the robot and Himiko ultimately get down in ways only a sex robot

and amnesiac girl can.

And

that’s where everything breaks.

The

android’s creator says that the only way to free people is with a big jolt of

sex, and that’s exactly what happens. After a little lovin’, 964 is wracked by

incredible pain, which seems to be the result of his sudden understanding of

his own condition. He’s no longer a walking vibrator, but a shell of a man,

horribly aware of his backwards evolutionary step.

Whether

through the sex or 964’s subsequent power, Himiko is also unhinged, and

violently so. She’s been repressing memories of her own, which imply some role

in 964’s creation. And once the flood gates open, there’s no closing them.

Himiko

staggers through the subway, vomiting profusely. I might suggest to an

Alzheimer’s research panel that excessive vomiting, followed by rolling in the

result and, er, eating it, might help with memory loss…but then again that’s

probably not a good idea. Just try to tell Himiko that.

But as in

Tetsuo,

the fluids and kinetic movement are flashy ways of making a point. Trouble is, Fukui isn’t all that

clear about his intent. Rather than following the ‘pain to power’ thesis, he

establishes 964 and Himiko as a massively dysfunctional couple. First she helps

create him through a sickeningly violent process, then turns him into her own

slave, alternately caring and dispensing abuse. There is a final bizarre

physical transformation, but it’s a manifestation of that relationship, rather

than of a pure will to power fantasy.

Fukui tries to use the same stylistic

camera and narrative style that worked so well for Tsukamoto, but simply

doesn’t have the skill to pull it off. That really limits the film, and the

experimental narrative sags. His camera moves excessively to hide a limited

budget, and Fukui

only occasionally shoehorns meaning into the jarring movement.

Even with

those issues, there’s one overriding flaw that keeps Pinocchio from being as

unsettling and effective as Tetsuo: it’s too damn long. Fukui imitates the mad dashes through Tokyo that worked so well for his

inspiration, but he indulges himself both at greater length and slower pace. At

almost 100 minutes this is too long by half an hour.

There are

some really fun and intriguing ideas here, though. Before Bishop was revealed

as the creator of his own line of androids, 964’s morally dubious creator seems

to be making sex dolls in his own image. And I’m really interested in the

intersection of violence and memory, and how the result affects one’s ability

to relate to anyone else. That’s a huge part of the subtext here, but it almost

seems to be unintentional, making it almost too ‘sub’ to work.

There’s

also some fun humor — I love Himiko taunting the android’s pursuers, as well

as the final sequence when 964 takes hold of his own power. I certainly

wouldn’t blame anyone for completely missing Pinocchio‘s point,

however, which is just a forthright way of establishing my own critical escape

route when it’s revealed that this is actually a Heimlich Maneuver

instructional film. If you want vomit, you got it.

(Buy

it here from Amazon.)

Rubber’s Lover

(1996,

Japan, Shozin Fukui)

In

In

response, this film is for anyone who thought Pinocchio √964 was good

in theory, but too long, too scattered, or simply too thin. Fukui’s back on the

‘psychic power through physical pain’ trip, but he articulates it with far more

skill. Here his images are even more reminiscent of Tetsuo and Videodrome,

but this also feels more like a whole film, rather than an idea stretched too

far.

A trio of

scientists have been working for one of those classic shadowy organizations,

performing experiments to unlock the secrets of the mind. (Cue theremin,

please.) Shimika is the loner, and he thinks the drug ether is the key. The

remaining pair, Motomiya and Hitotsubashi, have been experimenting with a device

called the Digital Direct Drive, which bombards a subject with aural and visual

stimuli, essentially torturing the poor bastard until (a) he unleashes a wave

of psychic energy or (b) his head explodes. Option A doesn’t seem to happen

very often. In fact, neither technique

has a survival rate above .000.

And time

is running out for all three. Their corporate master sends a sexy lackey,

Akari, over to terminate their funding. Not such a good idea, since Motomiya

has been behaving erratically, and Shimika is addicted to ether, perhaps on his

way to becoming his own successful guinea pig. The lackey arrives as Motomiya

has decided to take matters, and the fate of Shimika, into his own hands.

And

that’s where (all together now) everything breaks.

Pumped

full of ether, wrapped in rubber (which provokes shock by depriving the body of

oxygen) and bombarded with evidence of his own violent past, Shimika

essentially becomes a scanner. The ether overload channels the power outward —

without the drug, the waves roll around in the skull and his head threatens to

go the way of so many others before it. The ‘power through pain’ concept

finally comes to a real fruition, and Shimika becomes the only one in all three

of these films to really achieve some sort of real evolution, even if the

effect is ultimately short-lived.

Whatever

experience Fukui gained between Pinocchio and this film was

invaluable, because he’s far more in control of the camera. The grainy black

and white creates scenes with a ridiculously uncomfortable atmosphere, and the

effects are more cleverly shot. And where his last film had screaming maniacs

instead of characters, here Fukui creates some immediately recognizable

personalities, most of which he uses well. I was scared for, and of, Shimika,

and even enticed by the oppressive eroticism between Akari and the scientists

female assistant.

This

isn’t a real finale for the cyberpunk barrage that began with Tetsuo,

but it is an effective summation. The technology on hand is essentially common,

and the scenes of bombardment by the Direct Digital Drive are powerful even

though the basic image of a guy with his head stuck in a TV has become debased

currency. Fukui belives in it, and that’s what makes this film work, and in

fact what makes the whole genre. There’s no irony here, but an inkling that we

might be relying on the wrong things, and fascination mixed with a genuine

terror of the consequences.

Finally,

one constant in all three films is that, during the process of transformation,

violence is not only done to the characters, but perpetrated by them as well.

It’s a bleak and horrifying worldview. That’s where a lot of the desperation

comes in — I don’t know if it’s a perversion or ratification of the punk ethos

— since the final effect can only be realized by savaging those around you. If

that’s the case, maybe it was inevitable that a cyberpunk savior like Neo would

show up to make us all feel better. Or not.

(Buy

Rubber’s

Lover here from Amazon. Considering the 16mm source, Unearthed

Films has done a great job with both of these Fukui films, each of which looks

and sounds as good as can be expected from such cyberpunk curios. Special

mention has to go to the menu design, which I really enjoyed.)

Thanks

for checking out the first column. As always, if you’ve got comments (derisive

or supportive) shoot ’em over to russ @ theporkstore.org. I check facts pretty

thoroughly, but with foreign films and smaller stuff misinformation abounds. So

if you notice any small inaccuracy or outright lies, please let me know. If

there are pairs or trios of films, mini-movements or specific filmmakers that

Chud really needs to stroke, make yourself heard. Future installments will

feature more festival coverage, express love for a couple of my favorite

character actors (Warren Oates and Don McKellar) and I’ll hit the output of

filmmakers like Lars von Trier, Yasujiro Ozu and, when I’m feeling mighty and

capable, Luis Bunuel. That might take a couple of installments.

Generally,

I’ll keep the content limited to movies that are in print in North America on

DVD, though at times I’ll have to range further abroad or even (gasp!)

encourage some VHS rentals.

Next week

will be dedicated to Wong Kar-Wai’s pair of Hong Kong love stories, 2046 and

In

The Mood For Love. After that will be a Chud exclusive look at the DVD

restoration of the oddball animated film Rock And Rule. I went to Boston last

month to check out the process and can’t wait to talk about it.

Discuss this column right here on our message boards.

BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

Universal has already sunk lots of money into the film American Gangster – both Denzel Washington and Benicio Del Toro had pay or play deals when they signed on to the film just before it imploded. That, of course, means that they got paid for doing diddly shit, which I am under the impression is a familiar situation for many of our daytime message board posters.

Universal has already sunk lots of money into the film American Gangster – both Denzel Washington and Benicio Del Toro had pay or play deals when they signed on to the film just before it imploded. That, of course, means that they got paid for doing diddly shit, which I am under the impression is a familiar situation for many of our daytime message board posters. Michelle Yeoh is a hot property in Hollywood this summer, as Mission: Impossible 3 and the Hannibal prequel are both looking to land the Asian lovely. She had been in talks with the M:I3 folks for a while, but it was while visiting the Cannes Film Festival that Yeoh was approached by the Hannibal crew.

Michelle Yeoh is a hot property in Hollywood this summer, as Mission: Impossible 3 and the Hannibal prequel are both looking to land the Asian lovely. She had been in talks with the M:I3 folks for a while, but it was while visiting the Cannes Film Festival that Yeoh was approached by the Hannibal crew. The website for the Sundance hit The Chumscrubber is online, and it’s worth checking out just for its amazingly impressive cast listing. They’ve got John Heard, William Fichtner, Carrie Ann Moss, Ralph Fiennes, Glenn Close, Allison Janney, Jamie Bell, Rita Wilson and the still-shamefully -cute-to-me-even -after-I-met-her-underage-self Camilla Belle.

The website for the Sundance hit The Chumscrubber is online, and it’s worth checking out just for its amazingly impressive cast listing. They’ve got John Heard, William Fichtner, Carrie Ann Moss, Ralph Fiennes, Glenn Close, Allison Janney, Jamie Bell, Rita Wilson and the still-shamefully -cute-to-me-even -after-I-met-her-underage-self Camilla Belle.

Here’s some good news for fans of Shaun of the Dead: Nick Frost, who played Ed in that film, did a show in the UK called Danger! 50,000 Volts, and it’s finally coming to the US (Now somebody get Spaced over here. Not for me – I imported it from the UK. But for the rest of you. It’s amazing!). I am working out an interview with Nick sometime soon (my third with him – at this point I think I have to make him my firstborn’s godfather or something), and I hope to have a review of this set for you before it hits stores. In the meantime, here’s the press release – and pay special attention to the info on zombies…

Here’s some good news for fans of Shaun of the Dead: Nick Frost, who played Ed in that film, did a show in the UK called Danger! 50,000 Volts, and it’s finally coming to the US (Now somebody get Spaced over here. Not for me – I imported it from the UK. But for the rest of you. It’s amazing!). I am working out an interview with Nick sometime soon (my third with him – at this point I think I have to make him my firstborn’s godfather or something), and I hope to have a review of this set for you before it hits stores. In the meantime, here’s the press release – and pay special attention to the info on zombies… Welcome

Welcome

Specifically,

Specifically, Fast

Fast In

In I approach my THUD duties with the best of intentions. I would like to have this column to you more often, but the honest truth is that it takes me multiple hours to put one of these together, and I don’t always have a solid block of time to give to the endeavour (thus the sporadic THUD Newsbreaks, keeping you informed between columns).

I approach my THUD duties with the best of intentions. I would like to have this column to you more often, but the honest truth is that it takes me multiple hours to put one of these together, and I don’t always have a solid block of time to give to the endeavour (thus the sporadic THUD Newsbreaks, keeping you informed between columns).

You can join the club at

You can join the club at  amount of money to tens of millions of dollars is that the people around you dramatically change.

amount of money to tens of millions of dollars is that the people around you dramatically change. Justin Timberlake is continuing his burgeoning acting career with a guest stint on what will probably be the final season of NBC’s Will and Grace. The former member of N’Sync and current holder of the sobriquet “The Trousersnake” will be playing gay – he’s going to be Jack’s bad boyfriend. Of course I know some people who tell me he wouldn’t be playing gay, but these are the same people who tell me that every single human being who has ever appeared in a movie or on television is homosexual. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

Justin Timberlake is continuing his burgeoning acting career with a guest stint on what will probably be the final season of NBC’s Will and Grace. The former member of N’Sync and current holder of the sobriquet “The Trousersnake” will be playing gay – he’s going to be Jack’s bad boyfriend. Of course I know some people who tell me he wouldn’t be playing gay, but these are the same people who tell me that every single human being who has ever appeared in a movie or on television is homosexual. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. when Tim Robbins says something political – who wants to hear the politics of some stupid actor! – but they back the Millers and Schwarzeneggers of the world.

when Tim Robbins says something political – who wants to hear the politics of some stupid actor! – but they back the Millers and Schwarzeneggers of the world. more complex than people were expecting. But it’s that complexity that I love; while I like the formulaic aspects of the other L&O shows, there’s something about the wheeling and dealing behind the scenes of a trial that I just think is cool. It’s also possible that this show was portraying law enforcement and the justice system a little less black and white than the other L&O shows.

more complex than people were expecting. But it’s that complexity that I love; while I like the formulaic aspects of the other L&O shows, there’s something about the wheeling and dealing behind the scenes of a trial that I just think is cool. It’s also possible that this show was portraying law enforcement and the justice system a little less black and white than the other L&O shows. and things. I think the show will be a little bit different because of it, but Jennifer is so excited about everything right now…"

and things. I think the show will be a little bit different because of it, but Jennifer is so excited about everything right now…" To make matters worse, Moore has left LivePlanet, the production company behind Greenlight, to start his own company.

To make matters worse, Moore has left LivePlanet, the production company behind Greenlight, to start his own company.  bigwigs think that the show is a ponderous waste of effort for both creators and fans, filled with faux imagery and meaning solely to trick people into thinking that something is going on.

bigwigs think that the show is a ponderous waste of effort for both creators and fans, filled with faux imagery and meaning solely to trick people into thinking that something is going on.