Hollywood loves a good franchise. The movie-going public does too. Horror, action, comedy, sci-fi, western, no genre is safe. And any film, no matter how seemingly stand-alone, conclusive, or inappropriate to sequel, could generate an expansive franchise. They are legion. We are surrounded. But a champion has risen from the rabble to defend us. Me. I have donned my sweats and taken up cinema’s gauntlet. Don’t try this at home. I am a professional.

Let’s be buddies on the Facebookz!

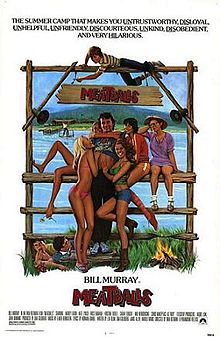

The Franchise: Meatballs — a very loosely associated series of stories centering on summer camps and the ribald and troublemaking antics of the camps’ young counselors. The franchise spans four theatrical films from 1979 to 1992.

The Installment: Meatballs (1979)

The Story:

It is yet another operational season at Camp North Star, a plucky but extremely second-rate summer camp. The camp’s director is Morty Melnick (Harvey Atkin), who has absolutely no control over North Star’s counselors or campers. The real honcho is the subversive and sarcastic head counselor, Tripper (Bill Murray), who delights in playing pranks on Morty and refitting North Star’s rules to his own rascally attitude. When the buses dump out this summer’s crop of campers, Tripper immediately takes a shine to shy outcast, Rudy (Chris Makepeace), and takes the boy under his wing in an attempt to boost his confidence. Summer passes and wacky but inconsequential stuff happens, then North Star participates in an epic contest with the neighboring rich-kid summer camp, Camp Mohawk. Then everything works out great for everyone. Except Morty, cause fuck that guy… even though he seems nice.

What Works:

Viewed back through the prism of time, critically speaking, Meatballs gets away with a lot by being a 70’s film, as it aggressively skirts the line between 70’s “hey, we don’t need to spell everything out for the audience” stylistics and what could simply be seen as incompetent filmmaking. Out of context, it is tempting to say the filmmakers just got lucky, because this feels an awful lot like a film made by people who didn’t know what the hell they were doing. But this film comes from producer/director Ivan Reitman and writer Harold Ramis, who in this same time period were also collectively responsible for Animal House, Caddyshack, Stripes, Ghostbusters, and Back to School. You know, five of the funniest comedies from the past three decades, and some of the funniest comedies of all time. So I think I can give them the benefit of the doubt here, at least as far as overall presentation is concerned. Meatballs is an imperfect movie. It barely seems like it is even trying to be a movie. But herein also lies its appeal. Its loose style plays directly into its pervasive charm. And the jokes come hot and heavy, almost all of which can be directly attributed to…

Bill Murray — in his first major film role after replacing Chevy Chase on Saturday Night Live. Ramis and fellow co-writers Len Blum, Dan Goldberg, and Janis Allen surely provided a lot of material, but knowing what we know about Murray, it is also safe to say that the man probably ad-libbed his way through the picture too. Whatever the ratio, this is Murray’s movie through and through. With Murray, Meatballs is a trifling but entirely fun and funny little film. Without him there would be nothing left but a few mild chuckles and some genuinely unfunny bits. Murray was and remains a singular comedic entity, changed only by age and his evolving taste in roles and projects. In films, he and Chevy Chase best represented the prevalent style of outsider comedy – characterized by anarchistic anti-establishment and anti-authority themes and laid-back, sarcastic heroes – that quickly became mainstream comedy by the end of the 70’s with the monster success of Animal House. But while Chase soon proved that he was really only as good as the material being given him, Murray has spent much of his career elevating projects with his mere presence. And Meatballs easily serves as the prototypical example of this.

Tripper isn’t really a character. I have no idea what his background is, or even what his overall “deal” is. What does he do the other nine months of the year when he isn’t at Camp North Star? What are his dreams, his goals? Why does he even work at North Star? No idea. But it doesn’t matter. Murray instills Tripper with that special Murray-ness. Murray’s appeal, aside from his killer delivery and timing, has always been his volcanic aura of confidence and the wry who-gives-a-shit look his face conveys. He makes not giving a shit seem exciting. And the ease with which he slips between dead-pan restraint and spastic outbursts makes him extremely versatile, able to play against any other type in any kind of scene. Just for an example, there is the classic Ghostbusters scene that, within the span of mere minutes, finds him delivering both the totally dead-pan “Yes, it’s true. This man has no dick” line and the over-the-top “dogs and cats living together; mass hysteria” rant. Both nailed with expert comedic form, both now classic comedy quotes from the 80’s. One almost has to wonder what state the Meatballs script was in before Reitman decided to cast Murray, as I could easily imagine that using Murray was something of a fix. Just toss Bill in here and he’ll figure it out. And he sure does. The film gets a lot of mileage from the context-less announcements Tripper makes over the camp’s PA system, almost all of which – after the film’s fantastic opening scene – are used as bumper transitions from one scene to the next. I wouldn’t be surprised if many or even all of these were added in post-production to beef up the laughs and help grease over the film’s clunky flow.

Murray makes Tripper a whirlwind of good-times, but as I said, Tripper isn’t much of a character. The only thing of real substance in Meatballs is the relationship between Tripper and shy Rudy. The chemistry between Murray and young Chris Makepeace is adorable enough to add some shades of depth to Tripper. Murray’s performance makes Tripper more than just a self-esteem booster for Rudy — the childlike way Murray approaches his scenes with Rudy makes Tripper the ultimate big-brother. He seems to enjoy acting like a kid with Rudy, almost as much for his own benefit as it is for Rudy. While I think this has far more to do with Murray having fun with these scenes than an actual creative decision on the part of the filmmakers, it still gives us the only insight into our central character that we get. The feeling is there. For Tripper to be so invested in Rudy, were this real life, we would safely presume that Tripper was maybe once a Rudy — the shy, new kid at camp who had a hard time making friends. Why else single Rudy out amongst the dozens upon dozens of campers, many of whom are presumably also not always having the best time? Probably just indifference on the part of the writers, and an attempt to make our snarky hero more likable. But given that Meatballs offers so little explanation for anything, this was the feeling I walked away with. Which I quite liked. The scenes of Rudy joining Tripper on Tripper’s morning jogs are really great, as is a cute and funny scene in which Tripper teaches Rudy to burp. Makepeace also gives the only sincere performance in the entire movie, which frankly goes a long way towards demonstrating the importance of sincerity even in wacky comedies. Much of Rudy’s smiling and laughter is presumably genuine – Makepeace cracking up at Murray’s ad-libs – but that hardly matters. You like the kid. When Rudy wins the long-distance running competition against Mowhawk, you feel Rudy’s release and Tripper’s pride. And that’s what doofy movies like this are all about.

Though I plan to discuss aspects of this in the next section, there is an appeal to the film’s purposeless flow. Especially in Act I. Meatballs has a staggering number of speaking roles, as we’re presented with a (presumably) realistic number of campers and counselors. Reitman and his editor, Debra Karen, jump and skip around the camp with zero regard for how well we’re following anything or committing characters to memory, but this does wonders for establishing environment and tone. Meatballs just offers itself to us, as is, take it or leave it, in that post-M*A*S*H way that consumed the 70’s for better and worse. The greater goal of the film isn’t telling us a story, but just presenting summer camp to us as a lived-in world. In this regard, Meatballs is very successful. I never went to summer camp, but I can walk away from Meatballs feeling as though I had; knowing what sort of dynamics develop between the campers and the counselors (who in the grand scheme of life aren’t that much older than the kids they’re wrangling). I was actually surprised by the feeling of sadness I had at the end of the film, when everyone is getting back on the buses to go home, even though I have no comparable camp experience to emotionally connect with.

Meatballs is also an oddly sweet film, considering the company it keeps with films like Animal House and Caddyshack. Though sexuality plays a major role in the film’s jokes, there is no nudity or much in the way of sexy-times. For example, the film features a scene that is basically a re-use of the scene in Animal House where John Belushi spies on some sorority girls walking around naked and, you know, doing things girls don’t actually do when they’re hanging out together. In Meatballs, our two most cartoonish characters, nerdy Spaz and chubby Larry, climb under the cabin belonging to our female counselors to eve’s drop while the girls are reading from a steamy romance novel. None of them remove their tops, and the scene feels relatively realistic, with the girls giggling at the book and horsing around. And ultimately the scene’s big gag is the humiliation of Spaz and Larry when they’re discovered. Furthermore, Larry and Spaz’s biggest moment of sexual triumph is when Larry wants to celebrate after Spaz holds a girl’s hand for the first time. “Held her hand? Spaz, you’re on your way!” Which made me smile.

The song “Meatballs” by Rick Dees is pretty stupid-excellent too.

What Doesn’t Work:

At the end of the day Meatballs works as it was meant to work, with most of the flaws in Reitman’s meandering, too-casual and disconnected presentation getting camouflaged by a combination of Altman-esque naturalism and the sheer magnetism of Bill ‘Fucking’ Murray. Which makes what a freakshow the script is sort of fascinating. So, keep in mind that these criticisms are mostly academic…

Considering that Meatballs was a popular success, it seems like a cruel nightmare for screenwriting teachers or anyone who subscribes to the methods set forth by Syd Field or Save the Cat, as it has no story, no structure, and no hero. Tripper is our protagonist, but only due to his domination of screen-time. He lacks almost all the requirements that usually designate a hero or even anti-hero. The closest thing Tripper has to an arc or stated goal in the film is his wooing of Roxanne (Kate Lynch), the head female counselor. But this is only of passing concern to him throughout most of the run-time and we can sense that it feels like a forgone conclusion to him from the onset. Tripper isn’t required to change or improve to win Roxanne’s heart — it is a “she’ll come around” situation, making it a C-plot at best. And Roxanne’s “coming around” isn’t even instigated by something impressive or commendable Tripper does either. It just eventually happens. Rudy is the character who feels like our protagonist. He has an arc, going from shy nobody to camp hero. But Rudy’s storyline is viewed through Tripper’s storyline, making Rudy’s arc a transferred success for Tripper. Rudy himself is a B-story. This isn’t really that weird, especially for a film like Meatballs, but it is more conspicuous in light of…

The total lack of story or even a basic conflict. Meatballs is the mid-point in what might be considered Harold Ramis’ trilogy of ‘ramshackle underdogs versus privileged assholes’ films, along with Animal House and Caddyshack. But unlike the Omega Theta Pi snobs in Animal House, Camp Mohawk plays no part in the story. They’re introduced at the very beginning, then midway into the film there is a random stake-less basketball game between Mohawk and North Star, and then we never see or hear about them again until we suddenly move into the climactic annual competition — a competition that isn’t properly set-up either. The fact that Mohawk is full of rich kids has nothing to do with anything, aside from using the average person’s innate disdain for the upper-class as a lazy way to paint them as villainous (if shit-talking during a basketball game is supposed to be considered villainous, then these writers clearly never played/watched a sport before). There are no characters in Mohawk, no leading face to symbolize their group. Shouldn’t there have been an evil head Mohawk counselor for Tripper to have a long-running beef with? Shouldn’t Mohawk have come to North Star to antagonize/prank our heroes at some point? The only villainous thing we witness the Mohawk kids do is bully Spaz during the opening credits (when the campers from both camps are climbing on the buses). Shouldn’t they have bullied Rudy? Specifically, shouldn’t the nameless character we’ve never seen before who Rudy beats in the long-distance race have been the leader of these bullies, so Rudy gets an added satisfaction to his victory? The whole damn movie builds up to that race! If nothing else, shouldn’t Spaz have gotten some vengeance here? It is incredibly strange, both structurally and emotionally, to climax the film with a long competition sequence between our heroes and characters whose faces we can’t even identify or differentiate — and who have up until now played no part in our heroes’ lives or conversations.

The valueless nature of Camp Mohawk ruins the entire point of a competition finale, because North Star doesn’t really have anything to prove. This isn’t a “we need to save the orphanage” type of story. There is absolutely nothing at stake, other than any human’s inherent desire to win. But that inherent desire is under-cut by the fact that our heroes don’t even give a shit. The movie even makes a big joke out of this fact when Tripper delivers what would normally be a rousing and inspiring speech, but Tripper’s big point is, “It just doesn’t matter if we win or we lose. IT JUST DOESN’T MATTER!” So not only is nothing important at stake, but neither is North Star’s pride. This is fitting with a subversive anarchy comedy of this era, where you want your heroes to not give a shit about such things, so what’s bizarre is that North Star wins. And not just wins, but wins fairly. In Animal House or, say, Revenge of the Nerds (a movie very much inspired by these Ramis/Reitman films), our underdogs are forced to play outside the system to win — with “winning” in Animal House coming in the form of ruining a parade for those who wish to enjoy it. You would expect a hero like Tripper to want to outsmart the rich kids or turn the competition into pure chaos.

Compared with movies like Revenge of the Nerds or Police Academy, Meatballs is a very gentle, friendly, and sweet film (the final moments between Tripper and Roxanne are so sweet that they’re almost out of place). Which makes a couple elements – that feel typical of that larger comedy movement – stand out awkwardly. Prankery is a big part of subversive comedy, as it is a way for our fringe heroes to otherwise affect an establishment they’re completely powerless within. The slippery slope with prankery is that it can easily cross over into bullying. The Mohawk counselors are presented as “bad” because they bully Spaz. Makes sense. But moments before that, Tripper encourages the other counselors to call Morty “Mickey” instead, which they all do with a laugh (and continue to do so for the rest of the film). This feels typical for a movie like Meatballs — except for the fact that Morty is kind of lovable. The film’s biggest running gag is that Tripper repeatedly pranks Morty by moving the sound-sleeping camp director and his bed to bizarre locations in the middle of the night. This is presented as all-in-good-fun, which is of course the veil most real-world bullying tries to hide behind. Point being: Morty should have felt deserving of this on-going treatment. Then there is the scene in which Tripper tries to rape Roxanne, which comes early in Tripper’s “wooing” process. Murray is basically doing a riff on his lascivious character from SNL‘s “The Nerds” sketches (with Gilda Radner), and at first it is funny in a Pepe Le Pew way. But once Tripper is literally holding Roxanne down while she is genuinely trying to get away and screaming for him to stop, the comedy starts to feel ‘boy’s club’ dated. And when it keeps going, it starts to get uncomfortable. No one would attempt such a scene in 2012.

Breasts Exposed: 0

Most Shameless T&A: The T&A is pretty tame. So I’ll just say the entire character of Wendy (Cindy Girling), whose sole personality trait is that she has awesome boobs.

Best Line: Upon first meeting a sulking Rudy.

Tripper: You must be the short depressed kid we ordered.

Best Prank: The final Morty bed-moving prank, where Tripper and the others have moved Morty’s bed, plus his nightstand and other bedroom amenities, onto a raft and sent it adrift in the lake.

Best Stickin’ It To The Man/Jerks Moment: When Tripper poses as the head counselor for Camp Mohawk while talking with a reporter.

Tripper: But the real excitement of course is going to come at the end of the summer, during Sexual Awareness week. We import two hundred hookers from around the world, and each camper, armed with only a thermos of coffee and two thousand dollars cash, tries to visit as many countries as he can. The winner of course is named King of Sexual Awareness week and is allowed to rape and pillage the neighboring towns until camp ends.

Most Awkward Moment of Sexuality: When a female camper reveals she has started menstruating, then is told that she can get pregnant from “almost doing it” with a boy.

Should There Be a Sequel: I guess? It is summer camp. Most of these characters were at the camp last year, and Rudy is coming back next summer. So, sure. Why not. Won’t be hard to think of another non-story like this one.

Up Next: Meatballs Part II.

DISCUSS THE FRANCHISE ON THE BOARDS

previous franchises battled

Critters

Death Wish

Hellraiser

Home Alone

Jurassic Park

Lethal Weapon

Leprechaun

The Muppets

Phantasm

Planet of the Apes

Police Academy

Psycho

Rambo

Tremors