Read Part 1 Here,

Read Part 1 Here,

Part 2 Here

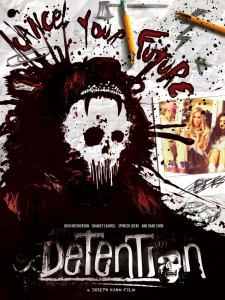

Here we are, the third and final part of my intense interview with Joseph Kahn and Mark Palermo. We dig into all sorts of topics here, and Joseph drops some of his next-level thoughts on filmmaking, all while explaining how a time-traveling bear became a part of the script, and this thing was built from the ground up on pop culture understanding. It gets more conversational here as we spiraled past the 45 minute mark of our conversation, but I think we covered some very interesting ideas, and the two definitely drew a line in the sand for their film

This interview took place after the second screening of Detention at SXSW 2011, after I’d published my review of the film. I met both Joseph and Mark for the first time to have this talk, and it’s interesting seeing the two discuss the film before its festival success and divisive-yet-positively-leaning critical response. You can tell even the writers are having trouble fully quantifying their odd little film, which is a challenge critics and audiences have faced in screenings since. Like this interview though, the film is extremely rewarding for those that are open to give it a shot and roll with its experimental oddity.

I’ll be slicing this interview up into three parts for publishing Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. Keep an eye out for all of them, and spread ’em around if you would…

Also, make sure you go out and support the film’s 10 theater release this Friday, if it’s playing at a theater near you. It needs your help much more than the big guys, as it’s do-or-die for the film this weekend. Get your tickets here.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Picking up where we left off…

Picking up where we left off…

Mark: Yeah, I’d say like the whole visual design of the movie is not in the script, it’s all character stuff and plotting issues. Some of the rhythm’s there, but not quite. It’s a little different when you see it in the film.

Renn: Well I mean shit, if you included the visual design it would read like a fuckin’ Burroughs novel or something.

[laughter]

Renn: So while writing a film so built on loaded references — be it the easily spotted Saw or Breakfast Club riffs — how do you individually decide what cultural pieces are going to get real-estate in the script?

Mark: I guess it just come naturally when we’re figuring it out, I’ve said before in interviews I’ve done that Detention is like very movie you’ve ever seen before and like no movie you’ve ever seen before. So we take all these influences of different films, but they’ve gotta fit. You know the Breakfast Club seemed like the right thing to do, the movie is shorthand.

Renn: It’s part of the grammar of high school movies at this point.

Mark: It’s part of the grammar, and then we go beyond that. The movie doesn’t feel like Breakfast Club when you’re watching it, and really in Detention that’s maybe 25% of the film. I look at the title Detention as a metaphor for the kind of state everybody’s stuck in, and not sure they’ll ever get beyond it. And the Elliot Fink character is the metaphor for all that as he’s literally stuck in the same place, as Riley’s emotions personified.

Joseph: I guess — getting back to your question about choosing the so-called memes to discuss in the movie — you have to look at it from the perspective that, one, we knew who we were making the movie for. Younger people, period. And that was very important to me. I feel like right now, kids today, teenagers don’t really have movies that speak to them. They have movies that speak to- I feel like the teen movies these days are older people looking at younger people and reminiscing about when they were young. For instance I feel like, with Juno, she didn’t use real lingo that kids use, she invented her own Diablo Cody lingo — which is great! — but no kids are talking like that. No kid is saying, like, “letgo my eggo preggo” or whatever. It’s not even terminology they would hear.

So anyway what we knew is if we wanted to do John Hughes, what we don’t want to do was repeat a John Hughes film for us, that we grew up on. We wanted to make a John Hughes film for them, and what that means is we need to be really focused on the current state of youth culture now. So we made a conscious decision. It came natural to me anyway, one, that there’s a rhythm that people see images that’s much faster, and two, calibrate it for younger audiences. For the most part we’re naturally man-children anyways,  with him being such a weirdo, Canadian that just absorbs every piece of pop culture and I’m a weirdo fuckin’ dude that does music videos. My job is having to stay aware of the latest bands and styles and clothes are, you know? But, we wrote it with all the jokes we wanted to do with the current state of pop as it is, but every once in a while we’d have to calibrate something.

with him being such a weirdo, Canadian that just absorbs every piece of pop culture and I’m a weirdo fuckin’ dude that does music videos. My job is having to stay aware of the latest bands and styles and clothes are, you know? But, we wrote it with all the jokes we wanted to do with the current state of pop as it is, but every once in a while we’d have to calibrate something.

For instance, there’s a point where Clapton has a scene on a skateboard with Riley, and then she turns to him and asks him to dance, and he says, “No, I have a date with Ione tomorrow.” Now she has to say a thing that Ione would say, that Clapton would like. Clapton likes Ione because he’s a music critic and Ione seems to know all this retro music, and he finds it fascinating that someone would be that well-informed on classic music references, which is why he’s after her as a music snob. So here Riley says, “oh you won’t dance, unless Ione plays Oasis.” Now we had a big debate about this, me and Palermo, about whether or not we should make it Oasis, because Palermo thought this is just the cheesiest, most blatant, obvious fuckin’ thing you could put in there- why would Clapton ever like Oasis? Because Clapton is cooler than that. Well my point was that younger kids today, who are under 18, don’t know who the fuck Oasis is. So they might have heard it from the radio or a video game or something, but they don’t know who they are. So it’s valid for him to say that, and we can’t pick anything too obscure otherwise the joke isn’t there- so it’s right on that level of, okay, that’s a 90s band that’s still relevant today, but only in a weird way. But only in that they seem strangely obscure, which is the kind of pop muscles we were trying to stretch.

Mark: I think we found a good compromise for that scene by having Clapton call them the “greatest Beatles cover band.” It’s like, alright that works.

Joseph: There were a couple places like that where we had to calibrate, because it may be popular enough, but not obscure enough. You’ll notice that there’s a lot of big pop songs in there like that.

Renn: Was there much improv on set?

Joseph: In terms of dialogue?

Renn: Dialogue, acting, rewriting scenes- anything.

Joseph: No

Mark: No

Renn: Was it all like, script scrip script-

Joseph: No, we spent three years on this damn thing. Nobody’s gonna change a line [laughs].

Joseph: No, we spent three years on this damn thing. Nobody’s gonna change a line [laughs].

Mark: We were pretty much sticklers for people saying our lines the right way. But you know Dane Cook’s a comedian, so he’d try our lines different ways, and we’d say “Alright Dane, that was hilarious, now do it our way.” He did get in one line that’s hilarious, when at the beginning there’s an art direction credit and he points at it and says, “This is ugly.”

Renn: Now that you mention it, those opening credits are something. They draw a line in the sand right away because- I mean they’re so fast.

Mark: I know. I hope people watch them in slow-motion at home on DVD so they can read my name.

[laughter]

Joseph: Let’s talk about credits in a movie. What the fuck are credits? What are they? Aren’t you supposed to be watching the movie at this point? Aren’t you supposed to be believing in this character at this point, and then you see Julia Roberts name up there. Now, is that Julia Roberts or is that freaking Pretty Woman? Who am I watching, what am I supposed to be doing here? So the entire concept of credits is weird, and then on top of it, on a modern typography level, people are used to credits in their lives now. You walk around and on any television show there are numbers floating around, and word are floating, and we have after effects and magazine and photoshop. And we wear credits, you know? The Urban Outfitters, Hot Topic idea of fashion where you wear a word-

Renn: You brand yourself.

Joseph: So the whole world is fused together with this symbology, and I was thinking, “well, if I’m gonna do this credit sequence, and we’re really playing with the idea that this is embedded into your world, I’m even going to make it two things: are we watching a movie? Or are we watching life? So that’s why I embedded it into the scene altogether, because now it’s like actually in it, and a line’s been crossed. The audience is like, “is that a credit sequence? Is that an art piece?” Well you know, ask yourself the same question when you watch any movie- what are you looking at?

Renn: There are a lot of films that try that kind of thing, but usually about halfway through they stop being clever, but these felt consistent and right the whole way through.

Joseph: Yeah, and I think the speed of how they’re done — and this is the second part of it — is once you’ve watched three, four, five times you don’t want to sit there- you know what that name is once you know, you see it’s whoever as the Executive Producer. Once you’ve watched a third, fourth, fifth time you’re going to get really bored because you know what it is, so it’s really calibrated for that

Joseph: Yeah, and I think the speed of how they’re done — and this is the second part of it — is once you’ve watched three, four, five times you don’t want to sit there- you know what that name is once you know, you see it’s whoever as the Executive Producer. Once you’ve watched a third, fourth, fifth time you’re going to get really bored because you know what it is, so it’s really calibrated for that

Mark: At what point did you find that you were into the movie? Was it right away or-

Renn: From the first shot. When I see the center comp and then she starts interacting with her own typography, I was interested, and then it kept going, and then it kept going, and then it kept going, and then 15 or 20 minutes later it was still the same level of density, so I was totally with it.

Joseph: Well I’ll be honest with you- I knew I could do that, I’m very confident as a filmmaker that I could bring that visual density — in fact I don’t think it even scratches the surface of what I can really do ultimately — but that’s why we spent three years on the script, that I brought Palermo on as a writer. I already knew it was going to be a dense movie no matter what, but that’s why we spent three years writing it because, hopefully, you’re following the story all the way through. I feel like the reason a lot of these movie slow down when you try to make these dense movies, you don’t care about the characters or the situation all the way through, but we really put all our muscle. I mean, the actual making of the movie is the fastest part of the process, in relative terms. Making it, I’m not saying it was easy, but it was the quicket part of the process. The writing of it was the most laborious, hardest part, and that was with Parlermo and I slaving over with coffee at two in the morning, asking, “Well, Riley, what does she need to do in this third act?” You know, “Should she fuckin… talk to Clapton here? What is Clapton doing to her? What is Clapton thinking?” And that to me is, hopefully, what carries people through the whole movie, while they’re enjoying the density of the filmmaking.

Mark: It’s really a labor of love for the both of us, we just put so much into it and hopefully, for me, the emotional arcs of the characters- it’s not just a spoof, it’s not a Scary Movie. It’s got to play as a teen film in its own right.

Joseph: We really wanted the characters to be real.

Renn: Well I think that, even on a first viewing, I was able to grasp a sense of these kids in a way also speak well of the casting and their performances.

Joseph: You really need to see it more, because I really did layer in some stuff. I have this whole theory… [hesitates as if contemplating a can of worms] …called five-dimension editing… [laughs] I say editing is four dimensions- it’s the space-time continuum you’re fucking around with, right? But the reality is that unlike normal perceptions of space time, you can stopping hopping over and rearranging images and all sorts of  things in the time graph, that go beyond a linear space-time continuum. So essentially you’re hopping into a different dimension, and that’s essentially what these kids are doing- they’re time-traveling into a different dimension, and the editing can do the same thing to. You’re gonna see a lot of edits that sort of mimic each other, over time. Like a movement that matches one in another scene, a breath that goes into a similar composition, and these are the levels that go beyond the crazy camera moves and the colors that you see, and that will even be more fun to break down when you watch it over and over again.

things in the time graph, that go beyond a linear space-time continuum. So essentially you’re hopping into a different dimension, and that’s essentially what these kids are doing- they’re time-traveling into a different dimension, and the editing can do the same thing to. You’re gonna see a lot of edits that sort of mimic each other, over time. Like a movement that matches one in another scene, a breath that goes into a similar composition, and these are the levels that go beyond the crazy camera moves and the colors that you see, and that will even be more fun to break down when you watch it over and over again.

Renn: Another random question- and, not really I guess. Tell me about the bear, and planet…

Joseph: Starclaw!

Renn: Ha, I knew it had “claw.” Tell me about that, because of all the things in the movie- that kinda takes the cake.

Mark: Well, I really thought that the centerpiece of the movie really needed a montage sequence, like in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off there’s this incredible scene in an art gallery, and it’s a musical sequence where the characters are looking at paintings and kind of recognizing themselves in them. That’s such kind of a strange thing to throw in the middle of the movie like that, and it seemed like Detention needed a point at which it kind of slowed down and became more inwardly reflective of everyone, so all the characters are in the scene and it ends on the bear, and the bear has a flashback. And the idea for that is in Wes Craven’s original Hills Have Eyes part 2, there’s a scene where the camera’s on one person, that person has a flashback, it’s on another person, they have a flashback, it moves to a dog, the dog has a flashback, so it was kind of funny that this bear could have a flashback. We’d always had the bear though, it didn’t come out of that scene.

Joseph: We were always thinking in terms of, what have you seen before, and how can we make it true, but make it completely different. So we knew we were going to have our music video sequence in the middle, and I want to do as much as I can on a visual level to make that sequence great — the montage of kids  listening to music, emoting, and being emo — and it was so funny that it was a perfect opportunity to do that Wes Craven trick there, where like, okay, we have this emo music video scene and we’re going to flashback on this bear too. It’s just such a fuckin’ crazy idea, that we got a big kick out of writing it.

listening to music, emoting, and being emo — and it was so funny that it was a perfect opportunity to do that Wes Craven trick there, where like, okay, we have this emo music video scene and we’re going to flashback on this bear too. It’s just such a fuckin’ crazy idea, that we got a big kick out of writing it.

Renn: It’s funny you mention parallel editing, I think you’d get a kick out of this- in New York recently they had this event where they projected The Shining mirrored over itself so that as you watched it, you were watching an overlay of the film in reverse as well at half opacity or whatever, and you can got to see how the film innately mirrors itself.

Joseph: That’s awesome.

Renn: I heard some kind of examples like… something like Shelley is talking about how good of a guy Jack is, meanwhile in reverse he’s pounding on the door with the axe or something.

Joseph: I love that.

Renn: So yeah, to even be conceiving of ideas like that or even toying with them in an edit, I think speaks well towards the potential longevity of the film.

Joseph: That sounds like music to me. That really affects my soul, hearing that.

Renn: Well, personally, I’ve always found something in the movies that really stick with me, have some quality in the editing-

Joseph: Well it’s a lost art form, editing on a certain level. As much as we have access to editing, the thing that’s happening is that in an art form as expensive as movie-making, editing isn’t being used in a unique way, editing is being used to find the lowest common denominator. It’s becoming democratic, where editing is where the director should really have the most control, and the most artistic vision in terms of what he wants to achieve, and what it ends up becoming is a toolbox for a producer to come in there and essentially whack your film away to an L-C-D consensus. And the whole process from the research screenings to even like, say, discussion online about how movies should be done a certain way and they listen to that. It’s like there’s no individuality, and it’s like you can hear people even poo-pooing the idea that a director should even have necessarily a complete vision, and that he should have had more people behind him, he shouldn’t have done that himself. At which point, he shouldn’t have done it in the first place!

Renn: That’d be a rejection of the auteur theory, certainly.

Joseph: And by the way, I’m not an auteur theory specialist, its as much Palermo’s script as mine, so on a core level, it’s both of ours. But ultimately when you get to that final stage and like, who is going to make that movie and actually do it, the director has to step in there and put his balls on the block and say, “This is  my movie, and this is the way the characters are gonna be, and this is the way the editing is going to be.” The actual cinema up there, someone’s going to have to make that call, and what I don’t like in Hollywood right now is that it doesn’t feel like anyone’s stepping in there and painting the damn picture.

my movie, and this is the way the characters are gonna be, and this is the way the editing is going to be.” The actual cinema up there, someone’s going to have to make that call, and what I don’t like in Hollywood right now is that it doesn’t feel like anyone’s stepping in there and painting the damn picture.

Mark: Yeah, I don’t know- reviewing a lot of movies I kind of got fed up with them as no movies felt like there were made by real people anymore. There’s this strange impersonality to all of them.

Joseph: Even Palermo as a writer- he’s on set all the time, and I valued his opinion because we wrote the movie together, but I think he respected at the end of the day, I’m gonna have to direct this thing, and my balls are gonna be on the line, and the decisions are going to be mine at the end of the day. I just think there’s a place for director’s to exist, especially in the craft of making the film and that was not my experience on my last movie, that’s why I did this independently, because I was going to get that, even if I had to pay for it myself. Which I did.

Again, please toss this on your Facebook or give it a RT if you would. This film deserves more discussion than it’s getting, especially considering the coincidence of another great meta-text flick coming out the same weekend. The difference is that this one lives or dies on this weekend alone, as it either does well and expands, or packs its bags for video. Please, don’t put it off. Help give it a shot for other people to experience this as it should be seen- big and loud.

Twitter

Comment Below

Message Board