Avengers Assemble #1 (Marvel Comics, $3.99)

By Bart Bishop

I’m a long time reader of Brian Michael Bendis. I haven’t, however, been a fan for a while. It’s been diminishing returns with Bendis, in my opinion, since his tenure began on The Avengers back in 2003 with “Avengers Disassembled”. That was the point when Bendis became fully immersed in superheroes, the serpent that eats its own tail. It’s not that Bendis and superheroes don’t inherently mix, as his revolutionary takes on Ultimate Spider-Man and Daredevil prove, but there’s a fundamental difference between those properties and Bendis’ work on The Avengers. The former two were natural, organic extensions of Bendis’ imagination, as he was given a clean slate with both characters.

Ultimate Spider-Man was built from the ground up, and Daredevil had only recently been knocked back into the public eye by Kevin Smith. There was a freedom and energy there, and any devotion Bendis showed to earlier incarnations of both characters was overshadowed by an imposition of his own style and characterization. With “Avengers Disassembled”, however, everything changed. For the first time Bendis felt constrained by the Marvel sandbox, with the grander scale ironically forcing the narrative to be reduced. “Disassembled,” almost ten years on, is an embarrassment of kitchen sink storytelling, with dozens of characters standing around all chattering in the same faux-Mamet voice (that voice that garnered Bendis early praise in his noir works like Goldfish, Jinx, and Powers), waiting for the next fight and being rewarded with a massive deus ex machina.

I’ll give what followed Disassembled, Bendis’ New Avengers, credit: it’s far more ambitious and engaging than Avengers Assemble #1. Perhaps I’m jaded by corporate interloping, but there’s nothing unique or fresh in these twenty or so pages of storytelling. As of now there are five Avengers titles: Avengers, Avengers Academy, New Avengers, Secret Avengers, and now Avengers Assemble. Each of those other four serve a unique purpose in terms of modus operandi and writer: the classic team, the next generation, the Bendis street level, and the Ellis black-ops. All Avengers Assemble does is aesthetically link up with the upcoming Avengers movie, which the cover graciously reminds us will be released on May 5, 2012. But is this the best story to be told, by the most suited writer and artist, to attract that same audience that walks out of theaters on May 5 into the intimidating world of comic books?

The setup is simple: a new team of villains, which is actually an updating of an old team of villains from the ’70s, has formed calling itself The Zodiac. Each member is named after, has a costume depicting, and has powers personifying their sign. Meanwhile, a new Avengers Tower has been built in New York City and the majority of the current lineup of each disparate team is there (including the likes of Wolverine, Spider-Man and Red Hulk, who don’t have any lines of dialogue) to greet the public and the media with fireworks and a speech from Captain America. The original Hulk then encounters an Army convoy under attack by Aquarius out in the deserts of…Utah? Mars? Finally the normals, Black Widow and Hawkeye, are in the midst of wetwork “in the middle of Latverian nowhere” and have to call in the heavies, Thor and Iron Man, when Taurus attacks. Fight, fight, cliffhanger, to be continued…

This is all standard superhero fare, but it’s all greatly accessible for the new reader and for the casual filmgoing fan. First of all, the designs of the characters are almost identical to their movie incarnations. I wrote about brand synchronization once before, and frankly I understand Marvel’s approach. They’re a business, and have been very successful at building a cinematic universe since 2008 that has shown great respect to its comic book counter-part (Bendis even had a hand in writing Iron Man’s Nick Fury epilogue, the first mentioning of the “Avengers Initiative”). Captain America has wings, Thor doesn’t have a beard, but these characters iconically match with the upcoming movie without betraying past characterization.

Hawkeye, for instance, may be identical in appearance to Jeremy Renner’s Hawkeye but doesn’t appear to act like him. The Renner Hawkeye (and this is all conjecture here, gleaned from interviews and previews) is a stonecold sniper type, perhaps even more severe than the Ultimate version that had a bit of snarky wit to him. Bendis maintains the comic book personalities without acquiescing to any of the movies’ tweaks (so far). This isn’t an instance, thankfully, of Wolverine and Rogue suddenly having a father/daughter bond like in the X-Men comics of ten years ago. Bendis is juggling a lot of balls here, and for that I have to give him credit: he’s maintaining fidelity to the comics while streamlining the story to mimic the movies, all while introducing these characters to new or casual readers.

Compare this to the much maligned first issue of Justice League #1. That depicted a grim & gritty world of misunderstandings leading to aggression; of dark (k)nights and dank sewers; vague threats and vaguer enemies; and not even half the characters that will eventually star in the book. Avengers Assemble #1, however, spotlights the entire team (the six members in the movie) and Bendis nails them in terms of dialogue and action. Captain America is a “leader of men”, and even has a moment reminiscent of the USO “Star-Spangled Man” montage from last summer’s movie. Tony is the charming playboy, Hawkeye is an arrogant showboat, and Thor says “verily”. I’m a bit disspointed that Hulk has been devolved to his “Hulk smash!” persona, after all the work Greg Pak has done, but I suppose that’s a dictate from Marvel and not a decision by Bendis. My criticism is that this is all too safe and on-the-nose: there’s no subtlety or nuance. Still, it’s refreshing to have smiling superheroes that enjoy each other’s company and don’t torture or murder their enemies, and enemies that aren’t afraid to have a colorful motif and aren’t black trench coat wearing rapists.

A lot of that credit can be given to artist Mark Bagley. He’s old school Marvel at this point (I remember his work on Amazing Spider-Man twenty years ago, and of course Ultimate Spider-Man ten years ago), although he has branched out to other companies recently. His clean, colorful style is a bit too cartoonish for the tone Bendis is going for (make no mistake, Zodiac is more terrorist cell than mustache twirling evildoers, and the Avengers are framed as a sanctioned military task force), but he’s consistent in his sense of geography and action. There’s an admirable cause-and-effect to his panels, and an economy to the amount of space he uses (Hulk’s battle with Aquarius, for instance, takes up about four pages but conveys Hulk’s strength and frustration well). There’s a lot of story in this one issue, and Bagley doesn’t waste pages showing the progression of time (check out the carchase, Taurus chasing Black Widow and Hawkeye, near the end of the book). Kudos, as well, to his otherworldly design of Aquarius, lending a tried-and-true concept like water powers an otherworldly mystique.

There isn’t anything here readers of genre fiction haven’t experienced before, but it’s competent and classic in all it accomplishes. Each character is highlighted in a spot-on moment, the villains are clear (although their goals have built up a nice mystery), the action is compelling, and it’s anything but decompressed storytelling as the team is formed from issue #1 and already thrust into a narrative struggle. I can’t help but lament, however, Bendis’ waste of natural talent. He’s long since abandoned his true calling, crime fiction, even having steered Powers in a more traditional superheroic direction. Being waist-deep in superheroes can’t be his ultimate goal as a writer. Can it?

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

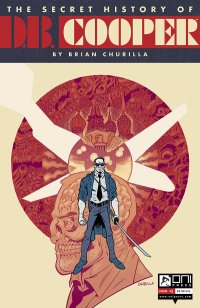

The Secret History of D.B. Cooper #1 (Oni Press, $3.99)

The Secret History of D.B. Cooper #1 (Oni Press, $3.99)

by Graig Kent

You may have heard the story of D.B. Cooper before. He was, up until 9-11, the most infamous hijacker in history, having ransomed a loaded Portland-to-Seattle Boeing 747 on the Seattle tarmac for $200,000 then, back in the air, he parachuted from the plane. He was never clearly identified, never found, and the FBI retains an open, and frequently active, case file. Literally nothing is known about the man, who he was, or where he wound up. Such a mysterious figure is ripe for fictional exploration.

The Secret History of D.B. Cooper gives you a one page set-up of this bizarre, yet real story, before you’re thrust into a wholly unnatural, even more bizarre realm. We follow the disheveled, trenchcoat and sunglasses-wearing, sword wielding Cooper as he interacts with a walking, talking, one-eared teddy bear, and takes on a monstrous behemoth. In a non-linear fashion, the story flips between this nightmarish fantasy world and a more normal reality in which a Russian heavy at the Kremlin eats goulash, while at a dive hotel Cooper snarks at other, presumably, CIA agents (apparently he’s one of them). They are disparate threads which actually all come together quite handily, as it appears Cooper’s talent is negotiating a sort of netherspace via psychedelic eye drops, where his actions within affect the real world. It’s Mission Impossible meets Dr. Strange only far weirder, in a good way.

Creator Brian Churilla cut his teeth on the Red 5 comic We Kill Monsters, Boom’s The Anchor and The Engineer for Archaia, amongst others, each delving heavily into both the metaphysical and monstrous, so he’s well prepared for this title from a storytelling capacity. His first major solo script, despite its irreverent structure, is actually quite straightforward, cleanly told and understood. Churilla’s illustrations, broad-lined and cartoonish, give an immediate sense of irreverence that deceptively masks the books’ more ominous undertones, but a nearly six-minute ambient soundtrack linked to in the backmatter resets the mood. Churilla’s style shares a similar sensibility to his Oni linemante, Sixth Gun‘s Brian Hurtt, perhaps less detailed and more fantasy driven, though, with a hint of Ditko inspiration, but they share a familiarity in character design and use of shadows. Accompanied by Keith Wood, the design of the book is fantastic, from the various logos to the plane iconography used in the peripherals and on the books’ captivating cover.

It’s an enjoyable read, but with the added touches it’s an even better experience, loaded with the mystery of how it all builds to Cooper’s infamous deboarding. I’m in.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

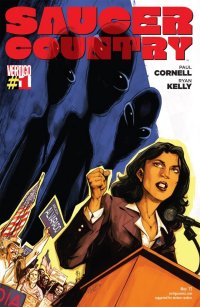

SAUCER COUNTRY #1 (Vertigo Comics, $2.99)

By Devon Sanders

I have no way to tell if I’m the only one but lately, what truly excites me is the idea of original comics creation. The idea that a person or persons strikes out into the world with an idea and convinces people to invest interest and coin into this thing that’s been rattling about their imaginations. When executed properly, it taps into the same spirit young men in the 1930’s and 40’s sent out into the world to unknowingly become comic book legends. That spirit is very much alive and devoid of spandex as politics and science fiction meet in current Demon Knights scribe Paul Cornell and artist Ryan Kelly’s brilliant, brilliant new comic Saucer C0untry #1.

Arcadia Alvarado, a young divorced governor of the state of New Mexico, is a woman-on-the-verge. The daughter of illegal aliens, she is being fast-tracked towards the presidency of The United States of America. On the eve of a life-changing announcement, strange memories begin to flood her mind; memories of places and things that certainly have no place on this Earth. On, perhaps, the most important day of her life, Arcadia Alvarado must tell the world. She WILL run for President of The United States of America and yes, she was abducted by aliens. Oh, that alien invasion is imminent.

Paul Cornell crafts one of the most intriguing comics I’ve read in a very long time. In Alvarado, he gives us a character who you can believe not only should be President despite seeing little green men but should be President BECAUSE she sees little green men. No mean feat. Cornell surrounds her with a supporting cast of characters whose patience and faith in everything will be tested and that more than anything, makes this reader want to come back for more. In asking for suspension of disbelief from all involved, including the reader, he’s tapped into a bit of brilliance.

Ryan Kelly, I’ve long believed, has been one of comics’ best kept secrets. Kelly draws characters whose expressions and gestures fit the mood and tone of the dialogue something not all artists understand. Where Kelly truly excels is character design. Kelly draws some subtlely attractive people while crafting gorgeous and most important, appropriate backgrounds for them to interact within. With Saucer Country, Kelly is given a world to build and is totally in his element.

Saucer Country #1 is a book I’ve been genuinely looking forward to and I can happily say it far exceeded my already high expectations.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

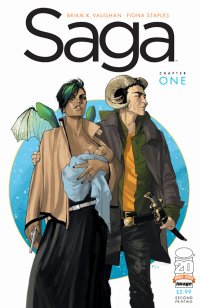

SAGA #1 (Image, $2.99)

SAGA #1 (Image, $2.99)

By Adam Prosser

Fantasy is strange. It is, in many ways, the purest, most unadulterated form of story—a genre that lets you crystallize anything you can imagine into a narrative, without any boundaries on what’s appropriate—and indeed, most of human literature and storytelling up until fairly recently falls under the broad umbrella of “fantasy”. But modern culture has an uneasy relationship with the genre. Unless it’s couched in certain acceptable literary paradigms—absurdism, surrealism, magic realism, postmodernism—it’s considered disreputable in many quarters, and certainly any story that makes a serious attempt at world-building (where the world in question doesn’t even pretend to be Earth) is rarely given any serious weight among the literati. Which is not to say they’re completely wrong to do so; after Tolkien arrived on the scene, fantasy spent most of the remaining 20th century labouring in his shadow, to ever-diminishing returns. The creation of the so-called “epic fantasy” genre led to an ironic lack of imaginative ambition, with far too many fantasy writers willing to simply slap a new coat of paint on Lord of the Rings and milk the results for book after book of an epic (and profitable!) “story cycle”. Things do seem to be turning around, and in fact there seems to have been a bit of a fantasy renaissance in recent years, with George R. R. Martin’s “Game of Thrones” series at the vanguard, but just as comic books are forever bound up with the superhero genre, “fantasy” has trouble staking out new territory without the ghost of Professor T. peering over its shoulder.

The hotly-anticipated new Image series Saga comes at the head of a wave of interesting creator-owned projects launched by Image this year for its 20th anniversary. It not only marks the much-anticipated return to comics of writer Brian K. Vaughn, it’s also his first real foray into fantasy. While his work has always had a SF element to it, it’s also had a highly grounded feel without a lot of the aforementioned world-building. On top of that, Vaughn has claimed Saga as a real passion project for him, and it’s also getting a lot of attention as a potential breakout project for rising star Fiona Staples, so needless to say, my interest was piqued.

The way the story is structured—it begins with the narrator’s birth—suggests that it’ll be spanning a long period of time, and probably undergoing a great many transformations along the way, but for right now it’s a kind of Romeo and Juliet story. The horned man Marko and the winged woman Alana come from opposite sides of an intergalactic conflict between magic and science, but they fell in love, she got knocked up and they ran away. Within moments of giving birth to their daughter, their respective factions are battering down the door, and the fugitive family is fleeing across a war-torn world towards a place where, apparently, rocketships literally grow on trees.

As you’d expect with the first chapter of a sprawling epic like this, there’s a lot of table setting and characters being introduced, including a monarchical family of TV-headed robots and a mercenary with a cat who can tell when people are lying, but the focus is squarely on Marko, Alana and their baby. With this, Vaughn has already vaulted the first common trap into which much fantasy falls: trying to introduce us to an overwhelmingly strange world before we actually care about anything that’s happening. Marko and Alana are completely fleshed-out characters right from their first scene, and the focus is on them, not the political turmoil that surrounds them. We get the backstory that we need to avoid confusion—an epic conflict that seems to have outgrown its original instigators, set against a fantasy universe with spells and prophecies but with also with futuristic technology and space travel—but it never overwhelms the story.

Of course, part of the reason the story doesn’t overwhelm like a lot of fantasy is that the characters and society aren’t particularly far removed from our own. Alana, Marko, and the other characters talk and behave exactly like modern day humans—like Brian K. Vaughn characters, in fact, snappy patter and all—which is great for relatability but might be a questionable move when the characters are a) not human, and b) live in a world so vastly different from ours. It can be a little discombobulating to see the television-headed robot members of a ruling monarchy, which on paper sounds like something out of “Dune”, talking like soap opera characters as they have sex. (Yes, the robots have sex.) It’s certainly a memorable technique, and the same bizarre mashup of relatable human drama against an insane SF/Fantasy backdrop works well for Carla Speed McNeil’s brilliant comic Finder, but as much as I love Vaughn’s work, this comic isn’t Finder, and I can’t help but think this is more a case of Vaughn simply having a set style for his writing that he has difficulty breaking out of. This complaint might seem a bit petty, I admit, and the story is so wildly imaginative that accusing Vaughn of not pushing himself may seem a little strange, but I do think that a thoroughly imagined universe deserves its own speech patterns and character concerns.

Of course, there are lots of other ways in which the comic breaks out of Vaughn’s usual template, and Staples here probably deserves some of the credit. Most notably is the way the narrator’s dialogue, written from the perspective of someone looking back from the future at these events, skates across the panels like scrawled notations on reality itself, sometimes even playfully drawing arrows to make her point better. Staples’ art, while a bit rough and occasionally lacking in detail, is also marvellously expressive; her Alana, in particular, leaps off the page as an instantly distinctive character who looks a bit like an 80s punk rock star, and her designs for costumes, creatures, and all the other SF gubbery that helps bring the world to life is instantly unique (again, the mix of archaic pomp and weird futuristic technology recalls Dune at times). She’s clearly a more offbeat collaborator than the more technically controlled draftsman Vaughn tends to work with, and she’s steering the story in more offbeat and unpredictable directions.

Despite whatever nitpicks I may have, Saga #1 is obviously a strong debut for an intriguing story by two creators with a vision, and it certainly doesn’t feel like a rehash of the kind of thing we’ve seen before. For many fantasy series, the implication of a sprawling, years-long epic to come feels like a threat; for Saga, it’s something I can actually look forward to.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

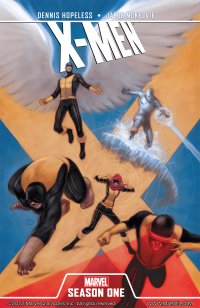

X-Men: Season One (Marvel, $24.99 )

By Jeb D.

Fans of Jamie McKelvie with $25 burning a hole in their pocket can quit reading right now and go out and buy this thing; more financially-constrained (or prudent) McKelvie fans at least need to add this to their Wish List, because this is some of the most eye-poppingly beautiful superhero art I’ve seen this year. Working again with colorist Matt Wilson, McKelvie’s version of the X-Men seems to pluck out the most kinetic elements of Byrne, adds the emotional range of Adams, and the cinematic perspective of Davis, to come up with a visual language for Marvel’s teen team that never sacrifices storytelling for beauty… but neither does it do the reverse: the X-Men, and their foes, are all as gorgeously-rendered as such creatures of fantasy should be, and their environment has the kind of two-dimensional reality that only comics can pull off.

There are probably no jokes left to be made about writer Dennis Hopeless’ name, but the fact is that the assignment he’s been handed here is… well, challenging at the very least. While Roberto Aguirre-Sacasca’s Fantastic Four: Season One had the advantage of working with the fairly simple and compressed setup for Marvel’s original flagship team, with only odd variations to be accounted for; their successors have had any numbers of starts, stops, reboots and rejiggers over the decades, and whether it was his decision, or Marvel’s direction, Hopeless manages to pretty effectively pick and choose bits and pieces from Lee/Kirby and Wein/Cockrum/Claremont/Byrne, smatterings of Thomas, Lobdell, and Whedon; and a soupcon of the films.

What he comes up with, though, is definitely his own X-world, and for all the occasionally conflicting elements that went into it, the result feels consistent and well thought-out. Jean Grey is our entrée, providing the internal monolog that runs through the story: the still-young X-Men are thrown into a variety of dangerous situations, and in the heat of the action, Jean’s recollections bring us up to speed on the team’s formation. Though we see her as the newbie coming into the established Xavier school, it’s in a world where mutation is, while feared and mistrusted by ordinary humans, not unheard-of: an “ugly secret,” but not a new phenomenon. No one dances around with the idea that these are just “special” students: right from the start, Jean knows what she and her new friends are, and Xavier’s charges are being trained to be superheroes, which is the sort of slightly absurd reality that, again, is one of the refreshingly comic-booky touches of what is evidently intended to be the X-Men’s origin of record for the Barnes & Noble graphic novel crowd. It wears its analogies about issues of race/gender/cultural tolerance lightly.

The storytelling is brisk, but jam-packed with introductions: all of the original X-Men (not the 1975 version), and such familiar mutants as Magneto, Unus, and the Blob, with room for brief, but striking, cameos for Scarlet Witch and Quicksliver, among others. The action setpieces are big and busy, with the kind of epic feel that the best X-Men storylines have always managed, but with some effective low-key contrast (Magneto’s “secret lair” is a nondescript office in downtown Manhattan).

That said, not everyone’s going to take to Hopeless’ structure: essentially, it’s alternating segments of soap opera/action over and over. Many of the individual sections are highly entertaining: one particularly amusing bit has Jean and Warren in the Savage Land, left tied up by their enemies to be dinosaur food, bickering over the fact that, for all their power, neither has the specific skills to get free of their bonds before the wonderfully rendered T-Rex shows up. The soap opera segments are a little more problematic: while that aspect of the X-Men remains at the heart of the team’s appeal, placing Jean as the only female in the school environment forces her to serve as the uncomfortable fulcrum for some Warren/Scott friction, as a fantasy figure for Bobby, and as a confidant for Hank; after a while, you start to wonder how a girl who can read minds could possibly wind up in so many messy adolescent situations. And, of course, “adolescent” is the key: Hopeless seems reasonably comfortable with language and attitudes that, while probably at least a decade behind what’s really at the core of today’s teenage experience, convey a familiar sense of the awkward youth we all remember.

To the extent that any of these Season One titles are “needed,” the X-Men probably benefit more from a “modern” version of their origin more than the Fantastic Four did, but the question remains, to what end? Is there some possibility of a new continuity for an ongoing series of hardcover bookstore titles? Not even the most deluded Marvel marketer could imagine that as reality. And if the monthly comics remain the core “canon,” (the backup story is a reprint of the first Gillen/Pacheco “ReGenesis” story), then the Season One books run the risk of being pretty, but irrelevant. Gotta admit, though, this one is DAMN pretty.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

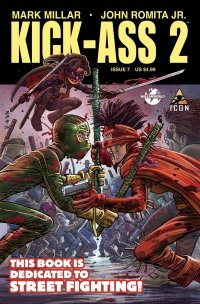

Kick-Ass 2 #7 (Icon, $4.99)

Kick-Ass 2 #7 (Icon, $4.99)

By Jeb D.

Well, what did you expect? Wall-to-wall violence? Yup. Cussin’ and name-calling? All here. Guts ‘n’ gore? By the bucketload. Long-underwear characters as deluded assholes? As promised.

I wouldn’t exactly call my relationship with this property “love-hate”: there’s nothing about it that I love, and I don’t know that I can muster enough interest to really hate it. But that is at least a decent approximation of my reaction: I’d like to dismiss it for the deliberate nature of its ugliness, but there’s enough that intrigues me to keep me coming back for more punishment at the hands of Millar and Romita.

If the signal moment of the first series came with the revelation about Big Daddy as a deranged comic-book geek, his Punisher-like backstory all a lie, the underpinnings of Kick-Ass 2 come at the beginning of this issue, when the massive battle of good guys and bad guys is kicked off (so to speak) with Kick-Ass and Red Mist face-to-face; and instead of the melodramatic speechifying of your typical hero/villain confrontation, Millar reminds us that these kids are barely off the playground: “You killed my dad! Oh, yeah, well you killed MY dad! Well, you raped my girlfriend! She wasn’t your girlfriend!” “Drop dead!” Like the Big Daddy scene, it’s the kind of uncomfortable self-loathing mirror that Millar holds up to a lot of his superhero work, where you’re never entirely certain just how many fingers he’s pointing at himself, or how many at his readers. And the outside perspective of the cops just reinforces the ludicrous notion that there’s anything “real-world” about the story (Hit-Girl is wanted for 61 murders–which may be mathematically accurate, but underlines the absurdity of it all).

My biggest problem with this second Kick-Ass series is that it’s not much more than a reset and escalation from the first. In particular, for all that Hit-Girl is an entertaining character (doubly so in the film), the conclusion of her arc in the first series was one of the few things that felt like something Millar hadn’t just slapped together over a few down at the pub, and her re-introduction felt like the worst kind of comic-book “resurrection.” In this issue, Millar and Romita push their physical abuse of her to new heights (lows?) in her bloody hand-to-hand fight with the brutal Mother Russia, only to have her emerge at the end with nothing to offer but an invitation to more carnage in the next series.

Still, there are moments from this comic that I can’t shake, and the picture of Red Mist, thrown from a building, lying broken on the street, is one of Romita’s most effective. I’m not the guy’s biggest fan–IMHO, he’s too often all action, no characterization–but to the extent that a comic as over-the-top violent and blood-spattered as Kick-Ass needed to exist, he’s one of the few that could pull it off, and the involvement of Tom Palmer brings added depth and strength.

I had hoped that the promise of a giant showdown between the armies of Kick-Ass and Red Mist would be a sort of street-level Apocalypse that would put a capper on the series, but (as with most comic-book Apocalypses) it’s just a setup for the next chapter. Which, I have to admit, I will probably check into, at least at first. But I’ll completely understand anyone else who can’t be bothered.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars